Sebaceous Adenocarcinoma

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

In a study of eyelid sebaceous carcinomas, 67% harbored point mutations in the p53 oncogene (Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010; 51:7).

- These mutations resemble the TP53 genetic alterations found in internal malignancies, and not the ultraviolet exposure associated TP53 mutations of skin tumors.

- Mutational inactivation of nuclear p53 may be involved in the progression of sebaceous carcinoma to invasive or metastatic disease (Ophthalmology 1998; 105:497).

Sebaceous carcinoma can occur in Muir-Torre syndrome (JAMA Ophthalmol 2014; 132:1025), a defect in the mismatch repair gene, but this defect does not play a role in sporadic cases (Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95:1686).

- Immunohistochemical staining for mutL homologue 1 and/or mutS homologue 2, DNA mismatch repair proteins, can prompt the search for internal malignancy and assist in recognizing Muir-Torre syndrome (Br J Ophthalmol 2015; 99:909).

- In 10 sporadic eyelid sebaceous carcinomas normal immunohistochemical staining for the four mismatch repair genes were found (AJO 2014; 157:640).

An etiologic role for human papillomavirus type 16 has been proposed, but in a study of 24 eyelid sebaceous carcinomas, only 1 showed HPV positivity (Human Pathol 2014; 45:533).

Prior radiotherapy, such as for retinoblastoma, is associated with secondary malignancy including eyelid sebaceous carcinoma, with a lag of about 20 years.

Epidemiology

In a study from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database — a system of cancer registries throughout the United States which collects demographic data — among 1,836 sebaceous carcinomas, 34% were eyelid tumors (Head Neck 2012; 34:1765)

- The most common site of sebaceous cell carcinoma on the body is the eyelid followed by the face, trunk, scalp and neck (Cancer 2009; 115:158).

- In the SEER study, eyelid sebaceous carcinoma had a higher histologic grade at presentation compared with nonocular sites and a higher incidence of regional and distant metastases.

The British Ophthalmological Surveillance Unit studied 51 patients with eyelid sebaceous carcinoma presenting between 2008 and 2010 (Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97:47).

- The estimated annual incidence was 0.41 cases per million population.

- Median age was 70 years, range 28–98 years.

- 57% were women, 12% developed on the caruncle (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sebaceous cell on the caruncle. Courtesy Mark. J. Lucarelli, MD.

Sebaceous carcinoma is the third-most common eyelid malignancy after basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

It is more frequent in the upper eyelid, attributed to the higher number of upper lid meibomian glands.

Simultaneous involvement of both lids can be observed and multicentric origin has been proposed rather than tumor spread from one lid to the other.

In Muir-Torre syndrome, there is an association with sebaceous carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, and gastrointestinal malignancy.

History

- Persistent nodular lesion of the eyelid meibomian glands

- May masquerade as a chalazion

- Biopsy is recommended for recurrent chalazion or presumed chalazion with associated adenopathy

- The hallmark clinical finding is loss of meibomian gland orifices indicating infiltrative growth originating in the sebaceous gland.

- Persistent unilateral blepharoconjunctivitis is another classic presenting sign.

- Sebaceous cell carcinoma is known as the “great masquerader” as it is often mistaken for a benign condition or other eyelid malignancy. This historically has led to a delay in diagnosis and potentially an increased risk of mortality.

Clinical features

- In contrast to basal cell carcinoma, there is more tendency to nodularity and flat tumor growth and less tendency to ulceration.

- Diffuse thickening of the eyelid may be mistaken for inflammation.

- Loss of normal eyelid margin architecture including loss of eyelashes, a hallmark of all lid malignancy.

- May have a yellow coloration due to retained lipid material, correlates with oil red-O positivity from intravacuolar lipid deposition.

- Intraepidermal extension may result in elevation of tarsal conjunctiva and bulbar conjunctiva (pagetoid spread) evident as increased vascularity.

- The primary lid lesion may be relatively small with pagetoid spread dominating the clinical appearance.

- Sebaceous carcinoma is also seen at nonocular sites including the back, cheek, and nose (Dermatol Surg 2014; 40:241).

- Primary sebaceous carcinoma of the lacrimal gland has been reported in limited case reports (Orbit 2012; 31:352).

- Metastasis to regional lymph nodes may be present in up to 18% of patients and associated with tumor size greater than 10 mm.

- Pre-auricular, parotid, and cervical lymph nodes

- Distant metastasis to liver and lung

Figure 2. Sebaceous adenocarcinoma. Courtesy Raymond Cho, MD.

Figure 3. Sebaceous adenocarcinoma. Courtesy Anne Barmettler, MD.

Figure 4. Sebaceous adenocarcinoma. Courtesy Mark J. Lucarelli, MD.

Figure 5. Sebaceous cell verrucous variant. Courtesy Mark J. Lucarelli, MD.

Figure 6. Sebaceous adenocarcinoma. Courtesy Rona Z. Silkiss, MD.

Diagnosis

- A generous representative specimen is helpful in making the diagnosis.

- Full-thickness eyelid biopsy can avoid sampling of superficial conjunctival reactive inflammation.

- Discussion with the pathologist regarding the suspicion of sebaceous cell carcinoma may be helpful to diagnose this uncommon tumor.

- If initial biopsy is negative and clinical suspicion remains high, consider a second biopsy and sending the specimen to an experienced ophthalmic pathologist.

- Special lipid stains may be helpful: Oil red O and Sudan IV.

- Immunohistochemistry for adipophilin can help establish the diagnosis.

- Lipid droplet-associated proteins are involved in the formation, maintenance and modification of intracytoplasmic lipid including perilipin (perilipin-1), adipophilin (adipocyte-differentiation-related protein, perilipin-2), tail- interacting protein of 47 kDa (perilipin-3), and myocardial lipid droplet protein (OXPAT).

- Adipophilin expression was studied in 82 periocular malignancies, and found in 100% of sebaceous carcinomas (n = 25), but also 100% of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (n = 9), 95% of basal cell carcinomas (n = 21), 73% of conjunctival squamous cell carcinomas (n = 22) and 60% of mucoepidermoid carcinomas (n = 5) (Ophthalmology 2014; 121:964).

- The pattern and intensity of adipophilin expression helps differentiate sebaceous carcinoma from other malignancies.

- Immunohistochemistry on sebaceous carcinoma can also demonstrate androgen receptors (AJO 2014; 157:687).

- In a comparative study, all 19 sebaceous carcinomas were androgen receptor positive, 6 of 18 basal cell carcinomas were positive, and none of 18 squamous cell carcinomas showed nuclear immunoreactivity (Am J Clin Pathol 2010; 134:22).

- p53 immunopositivity can identify atypical intraepithelial cells (AJO 2014; 157:186).

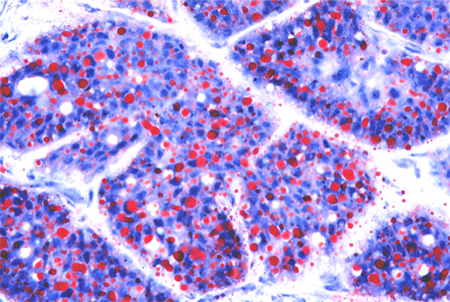

- Cytologic features of histologic analysis (Figure 7)

- Finely vacuolated cytoplasm

- High mitotic activity

- Giant cell reaction to lipid can be misdiagnosed as chalazion

Figure 7. Sebaceous cell pathology. Courtesy Mark J. Lucarelli, MD.

Clinical testing

Map biopsies were described by Putterman (AJO 1986; 102:87) as a means of identifying subclinical conjunctival intraepithelial disease

- Sixteen small-punch biopsies were recommended, spanning the palpebral and bulbar conjunctival surface.

- Intraepithelial pagetoid conjunctival infiltration may not be recognized on slit-lamp exam and may extend beyond clinically recognizable tumor margins.

- Map biopsies are random samples; more than 16 specimens may be taken to assist in identifying clinically silent areas of infiltration.

- Paradoxically, extensive pagetoid spread may produce more nondiagnostic map biopsies, due to artifact, compared with limited or no pagetoid spread (Arch Ophthalmol 2009; 127:961).

- Experience with clinical correlation between histopathology and biomicroscopy has improved the clinical recognition of intraepithelial tumor infiltration at slit-lamp exam.

- Pagetoid intraepithelial infiltration projects randomly as fine lacy lines, creating the impression of “skip areas,” actually oblique views of epithelial tumor growth.

- Fine lines of vascular infiltration accompany the thin fronts of epithelial tumor growth, best appreciated at the slit lamp against the relief of clear mucosa.

- Fine yellow spots represent adipose deposition, the clinical correlate of intravacuolar fat deposition seen on histopathology, accompanying epithelial and vascular infiltration, facilitating tumor recognition at the slit lamp.

- Corneal pannus may represent neoplastic infiltration (Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122:1402)

- When recognized by an experienced clinician, these clinical signs may be of greater value than map biopsies.

- Areas suspicious for tumor growth based on slit lamp biomicroscopy can be studied further by targeted biopsies, rather than the random sampling of the map biopsy technique.

- Some clinicians continue to favor additional random map biopsies as a means of cautious vigilance, however, map biopsies are no longer universally mandated.

- Clinicians who currently favor map biopsies will often sample more than the sixteen sites originally described by Putterman.

- Map biopsies are most useful in primary tumor staging.

- Questions remain about how map biopsies should be used to follow the tumor after initial staging.

- There is no consensus on the frequency and timing of surveillance map biopsies.

- The need for diffuse map biopsies in cases without clinical suspicion for pagetoid spread has been called into question, with a preference for targeted biopsies based upon exam as needed. This same article strongly recommends “expert dermatopathologic assessment” of frozen margins at the time of excision. (OPRS 2019, 35:419).

The current recommendation is to perform a sentinel lymph node biopsy on sebaceous carcinomas ≥ 10 mm in width (OPRS 2013; 29:57)

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

The Eighth Edition AJCC definition for eyelid carcinoma:

- T1 Tumor ≤ 10 mm in greatest dimension

- T1a Tumor does not invade the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T1b Tumor invades the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T1c Tumor involves full thickness of the eyelid

- T2 Tumor > 10 mm but ≤ 20 mm in greatest dimension

- T2a Tumor does not invade the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T2b Tumor invades the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T2c Tumor involves full thickness of the eyelid

- T3 Tumor > 20 mm but ≤ 30 mm in greatest dimension

- T3a Tumor does not invade the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T3b Tumor invades the tarsal plate or eyelid margin

- T3c Tumor involves full thickness of the eyelid

- T4 Any eyelid tumor that invades adjacent ocular, orbital, or facial structures

- T4a Tumor invades ocular or intraorbital structures

- T4b Tumor invades (or erodes through) the bony walls of the orbit or extends to the paranasal sinuses or invades the lacrimal sac / nasolacrimal duct or brain

- N0 No evidence of lymph node involvement

- N1 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral regional lymph node, ≤ 3 cm in greatest dimension

- N1a Metastasis in a single ipsilateral regional lymph node based on clinical evaluation or imaging findings

- N1b Metastasis in a single ipsilateral regional lymph node based on lymph node biopsy

- N2 Metastasis in a single ipsilateral regional lymph node, > 3 cm in greatest dimension, or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes

- N2a Metastasis documented based on clinical evaluation or imaging findings

- N2b Metastasis documented based on microscopic findings on lymph node biopsy

- M0 No distant metastasis

- M1 Distant metastasis

A retrospective review of 100 cases of eyelid sebaceous carcinoma using the AJCC 8th edition demonstrated the importance of both the T and N categories in prognosis, which was particularly worsened with at least T2c categorization or with the presence of any nodal disease. These impacted risks of metastatic disease, recurrence and survival, leading to recommendations for “strict surveillance testing for nodal and systemic metastases” (BJO 2019; 103:980).

In the SEER study cited above, regional or distant metastasis was evident on presentation of sebaceous carcinoma in 4.4% of ocular tumors, and 1.4% for nonocular tumors (Head Neck 2012; 34:1765).

- The overall rate of regional metastasis was 2.4%.

- There were no metastases among well-differentiated tumors while 13.9% of poorly differentiated tumors had metastases.

- Eyelid tumors were much more likely to be poorly differentiated (49.8%) compared with head and neck (22.7%) and other sites.

Differential diagnosis

- Chronic blepharitis and especially meibomitis can cause atrophic change and destruction that is benign and mimics sebaceous malignancy.

- The nodular elevation, especially on the conjunctiva, can mimic leukoplakia.

- Scarring and adhesions in the conjunctiva can mimic ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.

- Intraepithelial spread can mimic squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva and carcinoma in situ.

- The nodular lid elevation can mimic chalazion.

- Chronic lid thickening due to tumor infiltration can mimic blepharoconjunctivitis.

- Improvement with topical steroids may delay diagnosis.

- Basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma may cause similar appearing destructive lid malignancies.

- Lacrimal gland tumor when it arises in the lacrimal gland

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Clinical behavior

Eyelid disease spreads to the bulbar conjunctiva, dictating need for adjuvant cryotherapy and/or wide surgical excision.

Caruncle disease extends directly to the bulbar conjunctiva.

Tumor often extends to the adjoining lid at the canthus.

Small tumors are amenable to cure by surgery alone.

- Early diagnosis and recognition are critical.

For larger tumors, some advocate excision of the skin and eyelid disease by the Mohs technique.

- However, the primary focus with eyelid sebaceous carcinoma is on posterior extension to the bulbar conjunctiva, with slit lamp biomicroscopy and map biopsies if necessary, and serial evaluation as appropriate.

Deeper extension and larger tumors, with invasion of the orbit, recognized clinically and confirmed by biopsy, dictates the need for more aggressive surgery and/or adjuvant treatment.

- The risk of hematogenous spread and extension to regional lymph nodes is increased.

Regional lymphadenopathy recognized clinically and/or by sentinel lymph node biopsy dictates the need for lymph node dissection and possibly adjuvant regional radiotherapy.

Perineural invasion evident on histopathology is a risk factor for in transit disease and an indication for adjuvant radiotherapy (OPRS 2011; 27:356).

Distant metastases, most commonly to the lung, liver and brain, have no specific treatment or cure.

Medical therapy

There is little data to suggest efficacy for chemotherapy or immunobiologic therapy with this tumor.

Topical mitomycin-C (Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88:718) or 5-fluorouracil (Ophthalmology 2000; 107: 2190) may effectively reduce intraepithelial disease, but cannot be considered curative because of the depth of penetration by the drug and at best has an adjuvant role.

Radiation

External beam radiation can be administered as primary or adjuvant therapy.

Thirteen patients were treated in Japan with primary radiotherapy, all responded with no local disease evident at five years (Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 82:605).

- A total dose of 50 to 66.6 Gy (median, 60 Gy) was delivered in 22 to 37 fractions.

In another series of 16 patients treated primarily with radiotherapy the median dose was 60 Gy, delivered in 18-37 fractions, with a median of 30 fractions (Strahlentherapie und Onkologie 2012: 188:1102)

Radiation fields are set with a 10-mm tumor-free margin on either side — the eyelid typically measures 30 mm in width — therefore the entire eyelid and beyond are included in the typical treatment field.

A lens shield is mounted on the cornea, which protects the lens, but potentially limits treatment of bulbar conjunctival disease.

Irradiated tumors grossly disappear within 4 months.

Dry eye and cataracts are the primary long-term complications.

Surgery

Complete wide surgical excision of the lid should include approximately 3-5 mm of histologically proven uninvolved tissue on either side of the tumor with margin control by either frozen section histopathology or Mohs’ micrographic surgery.

- The decision to include a 3 or 5 mm margin – or even a larger margin of 7-8 mm – depends on the likely elapsed time that has allowed for tumor growth, and the estimate of tumor size.

- The tumor spreads radially with time, initially with thin fronts of extension – these may not be clinically evident, and are difficult to identify even on histopathologic examination of the surgical margin.

- Growth may be deep to the skin or conjunctival surface, such as along the tarsal surface, which may not be visible on biomicroscopy.

- The decision to remove additional full thickness lid, based on clinical judgment, balances vigilance in excising the tumor and a desire for tissue preservation.

Conjunctival disease, whether recognized by map biopsies or slit lamp biomicrsocopy, is treated by a combination of surgery and cryotherapy

- When extensive conjunctival treatment, excision and grafting are required, compromise of the ocular surface is expected.

When tumor has extended to the adjoining lid, at the canthus, a wide radial excision is needed for adequate tumor free margins.

When tumor growth invades deep into the fornices and/or canthi, with potential orbital invasion, a decision is made regarding exenteration.

- Untreated orbital invasion is initially more of a risk for local recurrence, but continued tumor growth, unrecognized in the orbit, can lead to regional and distant metastasis.

- It is not assumed that exenteration is necessary to minimize the risk of metastasis – potential deep invasion suggests that planes of tumor infiltration in the orbit can be difficult to identify.

- Globe sparing, more limited excision is an option for limited orbital extension.

- Study the orbit by random and contiguous sampling and assess the degree of orbital involvement – it is difficult to predict the direction of deep orbital invasion.

- Adjuvant radiotherapy is a reasonable option for potential tumor invasion; adequate data on the efficacy is unavailable.

Once tumor invasion to orbital fat or muscle is recognized, adjuvant radiotherapy and/or exenteration are two accepted management options, since no medical treatment has proven efficacy.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

Careful, long term monitoring is needed.

Local tumor recurrence is treated by surgery and cryotherapy.

Regional recurrence is treated by surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy.

There is no effective treatment for distant metastasis.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Extensive upper lid excision and reconstruction can compromise the integrity of the ocular surface.

Radiotherapy can compromise the ocular surface and intraocular tissues.

Tearing and chronic ocular irritation are multifactorial in these patients.

Diplopia may result from deep orbital excision.

Ptosis and lagophthalmos are predictable with loss of levator muscle.

Ectropion, trichiasis, and lid retraction may require multiple surgical repairs, particularly challenging in an irradiated field.

Disease-related complications

Thirteen patients with orbital extension were treated in New Delhi with exenteration, with or without adjuvant radiotherapy (Orbit 2012; 31:150).

- Recurrence in the lid was observed in 7/13 patients (54%)

- Time to local recurrence ranged from 3-24 months (median 8 months).

- Eleven of the 13 had clinical preauricular lymphadenopathy, underwent parotidectomy and lymph node dissection, and all 11 cases had nodal involvement on histopathology.

- No patient developed distant metastasis.

- Adjuvant radiotherapy may reduce the rate of local recurrence – recurrence appeared in 2 of 7 patients treated with post-operative radiotherapy (RT) and 5 of 6 patients who did not receive adjuvant RT.

In nonocular sebaceous carcinomas, identified through the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, only sixteen of 1,433 patients (1.1%) had regional lymphadenopathy identified, and nodal metastasis was not an independent risk factor for disease related survival (Laryngoscope 2013, 123:2165).

- Nodal metastasis occurred exclusively with poorly or undifferentiated tumors.

- Tumor grade was the primary risk factor for survival in this cohort of nonocular sebaceous carcinomas with a hazard ratio of 4.97 (p=.038) – there was approximately a five times greater probability of tumor related death with this risk factor than without the risk factor.

Nodal recurrence may occur more than ten years after primary tumor resection (JAMA Ophthalmol 2013; 131:1091).

Chronic pain is not infrequently reported by patients without clinical evidence of residual disease which creates a vexing challenge

- Prior disruption of periocular nerves may be responsible for the pain, possibly with aberrant regeneration

- Direct tumor extension may be responsible for the pain, with perineural involvement not clinically evident – difficult to confirm by biopsy.

- Mechanical irritation may be responsible for deep pain, but this may be difficult to rectify.

Death from sebaceous carcinoma continues to occur in a small number of patients.

- In a study of 43 patients treated at Moorfields Eye Hospital from 1976 to 1992, treated primarily with surgery in 37 and radiotherapy in 6 cases – 4 patients died from the tumor (Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82:1049).

- In a study of 60 patients treated at Wills Eye Hospital from 1974-2003, death from metastasis occurred in 6% (Ophthalmology 2004; 111:2151).

Historical perspective

In 1977 Tenzel published a case series of 3 sebaceous adenocarcinomas and urged that “the excision of a portion of eyelid beyond the most subtle conjunctival changes (is) necessary to obtain margins that are free of tumor.” (Arch Ophthalmol 1977; 95:2203).

Boniuk and Zimmerman in 1969 wrote that the tumor “may be more common than previously suspected.” (Arch Ophthalmol 1969; 82:66).

In 1965 there were 140 cases of eyelid sebaceous carcinoma reported in the literature, identified by Subramanian (BJO 1965; 49:93).

References and additional resources

- Aronow ME, Singh AD. Radiation therapy: conjunctival and eyelid tumors. Develop Ophthalmol 2013; 52:85.

- Chao AN, Shields CL, Shields JA. Outcome of patients with periocular sebaceous gland carcinoma with and without conjunctival intraepithelial invasion. Ophthalmology 2001; 108:1877.

- Condon GP, Browstein S, Codere F. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid masquerading as superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1985; 103:1525.

- Dasgupta T, Wilson LD, Yu JB: A retrospective review of 1349 cases of sebaceous carcinoma. Cancer 2009; 115:158.

- Dzubow LM. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid: treatment with Mohs surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1985; 11: 40.

- Esmaeli B, Nasser QJ, Cruz H, et al: American Joint Committee on cancer T category for eyelid sebaceous carcinoma correlates with nodal metastasis and survival. Ophthalmology 2012; 119: 1078.

- Gaskin BJ, Fernando BS, Sullivan CA, et al: The significance of DNA mismatch repair genes in the diagnosis and management of periocular sebaceous cell carcinoma and Muir-Torre syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95:1686.

- Gauthier A, Campolmi N, Tumahal P, et al: Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid and Muir-Torre syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014; 132:1025.

- Gonzalez-Fernandez F, Kaltreider SA, Patnaik CD, et al: Sebaceous carcinoma: Tumor progression through mutational inactivation of p53. Ophthalmology 1998; 105:497.

- Hata M, Koike I, Maegawa J, et al: Radiation therapy for primary carcinoma of the eyelid: tumor control and visual function. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie 2012: 188:1102.

- Hou JL, Killian JM, Baum CL, et al: Characteristics of sebaceous carcinoma and early outcomes of treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery versus wide local excision: an update of the Mayo Clinic experience over the past 2 decades. Dermatol Surg 2014; 40:241.

- Jagan L, Zoroquiain P, Bravo-Filho V, et al: Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid and Muir-Torre syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol 2015; 99:909.

- Jakobiec FA, Mendoza PR: Eyelid sebaceous carcinoma: clinicopathologic and multiparametric immunohistochemical analysis that includes adipophilin. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157:186.

- Jakobiec FA, Werdlich X: Androgen receptor identification in the diagnosis of eyelid sebaceous carcinoma. AJO 2014; 157:687.

- Kass LG, Hornblass A: Sebaceous Carcinoma of the Ocular Adnexa. Survey Ophthalmol 1989; 33:477.

- Kiyosaki K, Nakada C, Hijiya N, et al: Analysis of p53 mutations and the expression of p53 and p21 WAF1/CIP1 protein in 15 cases of sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2010; 51:7.

- Koreen IV, Flint A, Nelson CC, et al: Nondiagnostic conjunctival map biopsies for sebaceous carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2009; 127:961.

- Lin A, Bhorade AM, Sugar J, et al: Neoplastic corneal pannus in sebaceous cell carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2004; 122:1402.

- Margo CE, Mulla ZD: Malignant tumors of the eyelid: A population based study of non-basal cell and non-squamous cell malignant neoplasms. Arch Ophthalmol 1998; 116: 195.

- Milman T, Schear MJ, Eagle RC: Diagnostic utility of adipophilin immunostain in periocular carcinomas. Ophthalmology 2014; 121:964.

- Muqit MM, Foot B, Walters SJ, et al: Observational prospective cohort study of patients with newly-diagnosed ocular sebaceous carcinoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97:47.

- Pfeiffer ML, Savar A, Esmaeli B: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for eyelid and conjunctival tumors: what have we learned in the past decade? Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2013; 29:57.

- Pfeiffer ML, Yin V, Myers J, Esmaeli B: Regional nodal recurrence of sebaceous carcinoma of the caruncle 11 years after primary tumor resection. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013; 131:1091.

- Sa HS, Rubin ML, Xu S, Ning J, Tetzlaff M, Sagiv O, Kandl TJ, Esmaeli B. Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis and survival for sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid: observations in 100 patients. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019 Jul;103(7):980-984. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312635. Epub 2018 Aug 21. PMID: 30131380.

- Sa HS, Tetzlaff MT, Esmaeli B. Predictors of Local Recurrence for Eyelid Sebaceous Carcinoma: Questionable Value of Routine Conjunctival Map Biopsies for Detection of Pagetoid Spread. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Sep/Oct;35(5):419-425. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001343. PMID: 30865067.

- Sawada Y, MD, Fischer JL, Verm AM, et al: Detection by impression cytologic analysis of conjunctival intraepithelial invasion from eyelid sebaceous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 2045.

- Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, et al: Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids: Personal experience with 60 cases. Ophthalmology 2004; 111:2151.

- Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle RC, Shields CL: Sebaceous Carcinoma of the Ocular Region: A Review. Surv Ophthalmol 2005; 50:103.

- Song A, Carter K, Nasreen S, et al: Sebaceous cell carcinoma of the ocular adnexa: Clinical presentations, histopathology and outcomes. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008; 24: 194.

- Tetzlaff MT, Curry JL, Yin V, et al: Distinct pathways in the pathogenesis of sebaceous carcinomas implicated by differentially expression mRNAs. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015; online publication.

- Thomas WW, Fritsch VA, Lentsch EJ: Population-Based Analysis of Prognostic Indicators in Sebaceous Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Laryngoscope 2013; 123:2165.

- Tryggvason G, Bayon R, Pagedar NA: Epidemiology of sebaceous carcinoma of the head and neck: Implications for lymph node management. Head Neck 2012; 34:1765.

- Tumuluri K, Kourt G, Martin P: Mitomycin C in sebaceous gland carcinoma with pagetoid spread. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88:718.

- Watanabe A, Sun MT, Pirbhai A, et al: Sebaceous carcinoma in Japanese patients: clinical presentation, staging and outcomes. Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97:1459.

- Yeatts RP, Waller RR. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid: pitfalls in diagnosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1985; 1: 35.

- Yeatts RP, Engelbrecht NE, Curry CD, et al. 5-Fluorouracil for the treatment of intraepithelial neoplasia of the conjunctiva and cornea. Ophthalmology 2000; 107: 2190.

- Zurcher M, Hintschich CR, Garner A, et al: Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid: a clinicopathologic study. Br J Ophthalmol 1998; 82:1049.