Naso-Orbital Ethmoid Fractures

Updated July 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Naso-orbital ethmoid (NOE) fractures are common injuries found after high-velocity blunt trauma.

Epidemiology

There have been varying trends, but motor vehicle collisions and interpersonal violence are the 2 most common causes of maxillofacial fractures. Falls and sports injuries are less common causes.

The male to female ratio of maxillofacial fractures is 2:1.

Ocular injury has been reported in 24%–28% of facial fracture cases. Cervical spine injury is also found in 1.3% of patients with facial fractures and 4% of patients with facial injury from motor vehicle collision.

History

Specifics of the trauma including

- Mechanism of injury

- Timing

- Other interventions already undertaken

In conscious patients, history should focus on

- Breathing

- Vision

- Diplopia

- Occlusion

- Prior facial trauma

- Prior ocular disease

- Point tenderness

- Tearing

- Nasal airway obstruction

- Review of prior photographs

In addition to facial fractures and ocular injury, care often needs to be coordinated with other teams caring for

- Airway

- Cervical spine

- Any intracranial concerns

Clinical features

An NOE fracture centers on the frontal process of the maxilla and can also involve the ethmoid bone, lacrimal bone, nasal bone and frontal bone.

- The maxillary bone segment includes the inferior 2/3rds of the medial orbital rim and the lacrimal crests.

- The segment articulates with the medial orbital wall and nasal dorsum.

The inferior fracture line often extends through the inferior orbital rim lateral to the lacrimal crest connecting into the piriform aperture.

- The superior fracture line extends from the medial wall, through the medial rim above the canthal tendon, and into the nasal dorsum.

- As such, the fracture involves the medial canthal tendon–bearing bone segments and can lead to displacement or disruption (Figure 1).

An NOE fracture can occur in isolation from central midface trauma and is often bilateral in such circumstances.

- Nearby fractures of the frontal bone, frontal sinus, or inferior orbital rim are common in unilateral injuries.

- The NOE fracture is also a part of other named fracture patterns.

- Nasal fractures are classified by visualizing a coronal plane through the nasal bone where the fracture occurred, with Phase I being the most anterior portion.

- NOE fractures are elements of a Plane III nasal fracture.

- By definition, Phase III fractures through the nasal dorsum include the medial orbital rim.

- There is extensive literature regarding the management of nasal dorsum reconstruction, and the usage of bone or cartilage grafting might need to be considered.

- NOE fractures are also common elements of high Le Fort II fractures and Le Fort III fractures.

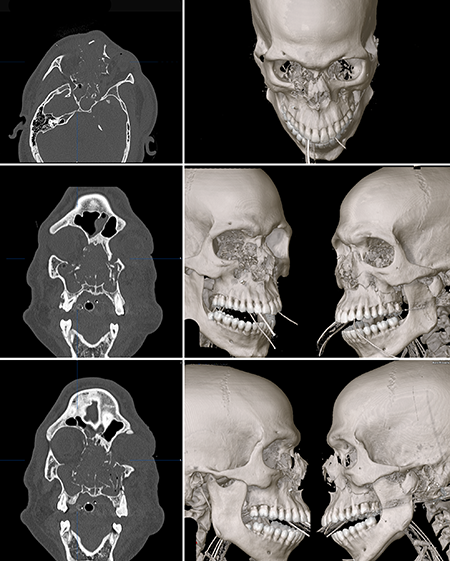

Figure 1. Complex facial fracture from a gunshot wound with a severely comminuted right NOE fracture (Type III) and less comminuted left NOE fracture (Type I).

Testing

- Clinical exam for standard signs of orbital and ophthalmic injury as well as various specific signs of an NOE or nasal bone fracture

- Periorbital bruising

- Nasal bone instability evaluated by pinching the nasal dorsum

- Telecanthus (greater than 40 mm intercanthal distance in any patient, less for Caucasians)

- Flattened nose with widened nasal dorsum

- Upturned nasal tip

- Narrowing of horizontal palpebral fissure

- Epistaxis, hematoma, or rhinorrhea on intranasal exam

- Subcutaneous emphysema

- Mobility or a “click” on palpation of the medial canthal tendon

- Signs of nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- CT scanning to evaluate the bone and soft tissue injury

- Thin-cut noncontrast maxillofacial CT scanning: Modern spiral scanning and thin cuts allows for multiplanar reformatting to view images in the coronal, axial and sagittal planes and also 3D reconstruction.

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

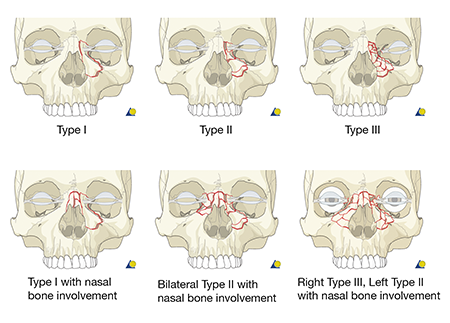

The degree of bone comminution within the maxillary bone segment can be used to subclassify the fracture.

- This has implications for the canthal tendon’s required management.

- Markowitz, Manson, et al. described 3 subtypes (Figure 2):

- Type I: Minimal comminution with the medial canthal tendon attached to a large bone segment

- Type II: Comminution of the bone fragments with the medial canthal tendon remaining attached to a bone fragment

- Type III: Comminution with disinsertion or disruption of the medial canthal tendon

Figure 2. Subclassifications of NOE fractures.

Risk factors

Seat belt has been reported to decrease the risk of maxillofacial injury by 72%.

Differential diagnosis

- Other facial fractures

- Zygomatic maxillary complex fractures

- Le Forte fractures

- Internal orbital fractures (floor and/or medial wall fractures)

- Optic canal fractures

- Soft tissue swelling

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

Extensive fractures of the midface are often associated with significant functional and cosmetic deformities if not repaired.

Identification of an NOE fracture and medial canthal disruption can be challenging with extensive edema, so a high degree of suspicion is needed and orbital imaging should be performed often.

A rare complication of Plane III nasal fractures and extensive NOE fractures that are not repaired is dorsal nasal instability or collapse.

- Airway obstruction has been reported and management can be complex.

Medical therapy

Although fractures ultimately might need to be reduced and repaired surgically, immediate medical therapy can include

- Avoiding nose blowing to prevent orbital emphysema

- Antibiotics for patients with signs or history of sinus disease

- Oral or IV steroids, which might reduce swelling, but have not shown a benefit to long-term outcomes

- Nasal decongestants

- Epistaxis treatments with clot extraction, application of topical vasoconstrictors, nasal sprays, or packing if necessary

- Ice

- Rest

- Bed head elevation

Surgery

- Indications and general concepts

- When neurologically and clinically stable, surgical repair involves open reduction and microplate fixation of unstable segments to more stable cranial and lower facial skeleton components.

- A Type I injury requires plating of the large unstable segment superiorly and inferiorly (see below).

- A type II injury requires transnasal wiring to stabilize the canthal tendon bearing bone segment (see below).

- A type III injury requires attachment of the tendon to a bone fragment or bone graft and transnasal wiring as per a type II injury.

- Incisions for NOE fracture exposure

- Depend on

- Fracture extend

- Location

- Associated injuries

- Include

- Superior fracture line access

- Coronal flap

- Existing lacerations

- Upper blepharoplasty incision

- Local vertical midline incision over radix

- Local horizontal incision over bridge of nose

- Lower fracture line access

- Gingiva buccal sulcus incision

- Lower eyelid transcutaneous or transconjunctival incision

- Small tear-trough incision

- Fracture repair technique

- Intranasal forceps can aid in repositioning/reduction of telescoped segments.

- Consider avoiding placing a plate that spans the entire length of the fracture segment.

- In attempting to cover both the most superior and inferior fracture lines, the large plate adds fullness that will be visible postoperatively.

- Rather, use a smaller plate for the superior and inferior fracture lines.

- Complete and wide exposure of the fracture lines is important.

- Over-dissection of an undisrupted medial canthal tendon causes bleeding into the subperiosteal space, resulting in possible medial canthal fullness.

- Medial canthal tendon repair

- Reduction of medial canthal bearing bone fragments (Type II) or a disrupted medial canthal tendon insertion (Type III) can be achieved with several techniques.

- Secondary telecanthus correction is challenging, so under-correction is common and long-term over-correction is near impossible, but some degree of intraoperative over-correction should be attempted.

- Transnasal wiring

- For a Type II injury

- A 28-G wire can be passed through 2 drill holes on the bone segment.

- These are then taken across the nasal bones at a level below the ethmoid arteries and superior and posterior to the lacrimal sac fossa.

- A 14-G angiocatheter can be reverse-passed across the nasal bones to provide a conduit that the wire can be passed through.

- Once across, the wire can be security to a plate or screw on the superior on the unaffected side.

- If a coronal incision has been made or the laceration approach extends across the nasal dorsum, simply bend them over the nasal bones toward one another and twist them together to tighten and then bend them together toward the unaffected side.

- Aiming the wire slightly superiorly toward the contralateral glabellar area can help in creating the proper vector and allow more purchase to support the wire.

- For a Type III injury

- The surgeon can attach the tendon to the bone segment with a 3-0 wire or heavy nylon suture, then wire as for a Type II injury.

- If the bone segment is obliterated, a bone graft can be used.

- A small split thickness calvarial bone graft harvested from the parietal bone will be of sufficient strength that a screw can be placed in the segment at the desired point of attachment of the medial canthal attachment wire.

- Barb wire

- An alternative and popular approach to a Type II or III injury is to use a titanium canthal barb through the skin or the caruncle.

- A major benefit to a barb approach is that in a type III injury, the missing bone segment is not an issue; the barb is passed through a plate placed deeper in the orbit and this creates adequate support for the tendon.

- Here a stab incision is made either just below in the inferior canaliculus or directly in the medial canthal tendon with an 11 or 15 blade or through the caruncle with a Westcott scissor and the canthal barb is placed through the wound.

- The desired point of attachment is again just superior and posterior to the lacrimal sac fossa and can be found by redraping the face and placing a needle full thickness through the medial canthal tendon and visualizing its point of contact with the bone.

- The canthal barb wire comes attached to a Keith needle, but a 14-G angiocatheter again facilitates passing the wire transnasally.

- Prior to passing the wire transnasally, a small prebent fixation plate is slid down the wire to create a deep pivot point for the wire to direct the medial canthal tendon appropriately.

- This plate should extend vertically over the superior orbital rim inferior to the trochlea and into the orbit posteriorly.

- It is fixated with 2 screws on the anterior portion of the rim and the most posterior hole, where the wire passes should be at the desired location superior and posterior to the lacrimal sac fossa.

- Creating a small fracture here allows the plate to go even further medial and reduces any undercorrection from the plate itself.

- After passing the wire through the plate, the wire is passed transnasally and can be fixed to plates on the contralateral side.

- If the fracture is unilateral, the wire can be wound around a screw or bent back and placed between the two screws and under the plate.

- As the wire is expensive and fragile, care should be used when sliding the wire through the plate.

- Mini-plate cantilevered fixation

- A Y-shaped mini-plate can also be directed posteriorly into the orbit on the affected side of the injury and secured to the lateral dorsum of the nose and then further secured to the canthal tendon with a nonabsorbable suture.

- This technique has the advantage of not requiring bilateral access and can also be done in the absence of stable bone.

- Although the barb can be unwieldy in that it breaks if over manipulated, it provides a more secure medial canthal attachment than a suture.

- Bone grafts to restore nasal projection and contour as appropriate.

- Septoplasty is often difficult in the acute NOE setting.

- Repair of other internal orbital, ZMC, or Le Forte injury components

- Tear duct intubation if the fracture involves injury to the proximal lacrimal drainage system

Other management considerations

Distal nasolacrimal duct injury can be difficult to assess for initially due to swelling, although bony disruption of the nasolacrimal duct can often be seen on axial CT sections of the midface.

Repositioning of bone fragments will give the best chance for restoration of the nasolacrimal duct passage.

Because probing is unlikely to treat a complete transection of the nasolacrimal duct (NLD) and can cause trauma in partially injured NLD, in patients with NLD obstruction, secondary dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) performed should be performed instead.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

Late repair requires extensive mobilization of fracture elements, often with osteotomies.

Because exposure needs to be greater to create a safe osteotomy relative to that needed for surgical repair, early repair is preferable.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Postoperative orbital hemorrhage

- Surgically drain if vision is compromised (canthotomy, cantholysis, placement of drain).

- Postoperative loss of vision

- Rule out optic nerve injury from displaced bone fragments.

- Repeat CT scan.

- Consider high-dose corticosteroids, although this has no proven benefit in traumatic optic neuropathy of any etiology.

- Rule out orbital hemorrhage causing an orbital compartment syndrome and manage with medical or surgical decompression.

- Infection

- Lower eyelid malposition, such as ectropion or retraction

- Postoperative telecanthus or persistent flattening of nose

- Requires adequate transnasal wiring

- Poor apposition of medial eyelid to globe

- Requires posterior attachment of medial canthal tendon to region of posterior lacrimal crest

- Epicanthal scarring or widening

- Can be treated with various microflaps, such as Mustarde, Y-V flap, Fuente del Campo, Uchida, or various modifications

- Epiphora

- Probing and irrigation to evaluate for nasolacrimal duct injury

Disease-related complications

The following can occur with or without surgical treatment:

- Dorsal nasal collapse

- Sensory nerve injury with persistent anesthesia

- Septal hematoma and secondary perforation

- Septal deviation

- Soft tissue injury complications

- Chronic sinusitis or mucocele

- Nasal airway obstruction

- Severe epistaxis (injury to anterior ethmoidal artery)

- CSF rhinorrhea

- Medial canthal displacement/telecanthus

- Nasolacrimal duct injury and epiphora

- Cerebral injury

- Facial deformities

- Nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- Ophthalmic injury

Historical perspective

Early publications on management of “nasoorbitoethmoid” fractures or “nasoethmoid orbital” fractures have discussed various aspects of fixation.

Markowitz and Manson’s 1991 classification schema for describing these fractures continues to be used.

Joseph Gruss described his own classification system with 5 types (NOE alone, NOE + central maxillary fracture, NOE + Le Fort II or III line, NOE + orbital dislocation and NOE + bone segment loss).

Gruss also described the role of bone grafting and nasolacrimal duct injury outcomes (17% of 49 patients required DCR).

Converse and Smith described nasal bone and canthal tendon involvement in internal orbital fractures.

Beat Hammer is often credited for the technique and adaptation of barb wire for medial canthal attachment.

Contributions to medial canthal tendon reconstruction technique also include Tessier, McCarthy, Shore, Antonyshyn, Callahan, Howard, Engelstad, Kirsten, Anderson, Bilyk, Rubin, Mustarde, and many others.

References and additional resources

- Manson PN. Chapter 34, The Management of Midfacial and Frontal Bone Fractures. In: Georgiade NG, ed. Plastic, Maxillofacial and Reconstructive Surgery. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997:351-76.

- Markowitz BL, Manson PN, Sargent L, et al. Management of the medial canthal tendon in nasoethmoid orbital fractures: the importance of the central fragment in classification and treatment. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 1991;87:843-53.

- Krausz AA, El-Naaj IA, Barak M. Maxillofacial trauma patient: coping with the difficult airway. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES 2009;4:21.

- Sargent LA. Nasoethmoid orbital fractures: diagnosis and treatment. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2007;120:16S-31S.

- Baumann A, Ewers R. Transcaruncular approach for reconstruction of medial orbital wall fracture. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 2000;29:264-7.

- Manson PN, Crawley WA, Yaremchuk MJ, Rochman GM, Hoopes JE, French JH, Jr. Midface fractures: advantages of immediate extended open reduction and bone grafting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 1985;76:1-12.

- Hammer B. Secondary Correction of Posttraumatic Deformities After Naso-Orbito-Ethmoidal Fractures: An Invited Technique. The Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Trauma. 2001:44–51.

- Titanium Barb Wire with Needle for Canthal Tendon Procedures. 2015, at http://www.synthes.com/sites/NA/NAContent/Docs/Product Support Materials/Brochures/MXBROTiWirBarbNeedleJ7094B.pdf.)

- Titanium Barb Wire with Needle for Medial Canthal Procedures: A Technique Guide.

- Engelstad ME, Bastodkar P, Markiewicz MR. Medial canthopexy using transcaruncular barb and miniplate: technique and cadaver study. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 2012;41:1176-85.

- Shore JW, Rubin PA, Bilyk JR. Repair of telecanthus by anterior fixation of cantilevered miniplates. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1133-8.

- Chaon BC, Lee MS. Is there treatment for traumatic optic neuropathy? Current opinion in ophthalmology 2015;26:445-9.

- Lima V, Burt B, Leibovitch I, Prabhakaran V, Goldberg RA, Selva D. Orbital compartment syndrome: the ophthalmic surgical emergency. Survey of ophthalmology 2009;54:441-9.

- Fuente del Campo A. A simple procedure for aesthetic correction of the medial epicanthal fold. Aesthetic plastic surgery 1997;21:381-4.

- Yamaguchi K, Imai K, Fujimoto T, Takahashi M, Maruyama Y. Cosmetic Comparison Between the Modified Uchida Method and the Mustarde Method for Blepharophimosis-Ptosis-Epicanthus Inversus Syndrome. Annals of plastic surgery 2014.

- Mustarde J. Epicanthal Folds and the Problem of Telecanthus. Transactions of the ophthalmological societies of the United Kingdom 1963;83:397-411.

- Uchida J. [Triangular flap method in medial and lateral canthotomy]. Keisei geka Plastic & reconstructive surgery 1967;10:120-3.

- Anderson RL, Nowinski TS. The five-flap technique for blepharophimosis. Archives of ophthalmology 1989;107:448-52.

- Johnson CC. Surgical Repair of the Syndrome of Epicanthus Inversus, Blepharophimosis and Ptosis. Archives of ophthalmology 1964;71:510-6.

- Gruss JS. Naso-ethmoid-orbital fractures: classification and role of primary bone grafting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 1985;75:303-17.

- Gruss JS, Hurwitz JJ, Nik NA, Kassel EE. The pattern and incidence of nasolacrimal injury in naso-orbital-ethmoid fractures: the role of delayed assessment and dacryocystorhinostomy. British journal of plastic surgery 1985;38:116-21.

- Converse JM, Smith B. Naso-orbital fractures and traumatic deformities of the medial canthus. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 1966;38:147-62.

- Smith B, Nesi FA. Orbital fractures and medial canthal reconstruction. Clinics in plastic surgery 1978;5:505-11.