Facial implants

Updated August 2024

Goals and indications

Etiology

- Facial implants can be useful in both cosmetic and reconstructive settings

- They can help address bony volume loss that occurs with aging, correct congenital abnormalities, improve overall facial skeletal symmetry and projection1 and play an important role in facial gender confirming surgery.2,3

- Facial implants have the benefit of being both a permanent form of volume augmentation, while also being easily reversible since they can be easily removed, particularly if a non-porous implant is selected.

- In some instances, they can be inserted at the same time as other surgical procedures, including rhytidectomy, and may enhance post-operative outcomes by improving underlying skeletal support.4

Types of implants

- Commonly used materials include silicone, porous polyethylene, expanded polytetratluoroethylene (ePTFE), mesh polymers, hydroxyapatite and polymethacrylate. Each material has pros and cons.5

- Silicone implants can often be inserted through a smaller incision due to their flexible nature, and are easier to remove, as a firm fibrous pseudocapsle tends to form around them.

- Porous implants allow tissue ingrowth which may enhance implant stability, but because of this, they are also more challenging to remove.

- In some situations, custom implants can be created from pre-operative imaging. Three-dimensional reconstructions of computed tomography scans can be used to design custom implants to address unusual congenital anomalies, specific defects following trauma/surgery, or certain aesthetic concerns.6

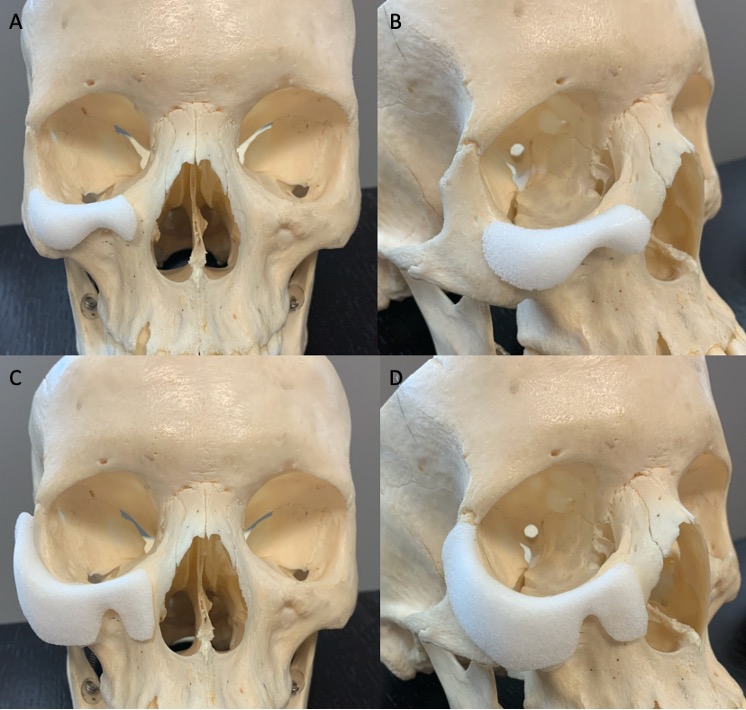

Orbital rim implants

- This implant sits along the inferior orbital rim and ranges from 1 – 3 cm in vertical height, with a cut-out for the infra-orbital nerve.

- Orbital rim implants can be used to improve lower eyelid position in patients with relative proptosis due to hypoplastic malar eminence, primary exorbitism, thyroid orbitopathy and post-blepharoplasty lagophthalmos.7-9

Figure 1. Orbital rim implant designs range from (A and B) those intended to augment only the anterior projection of the inferior orbital rim to (C and D) extended rim implants that reach laterally to the level of the zygomaticofrontal suture and medially to the nose.

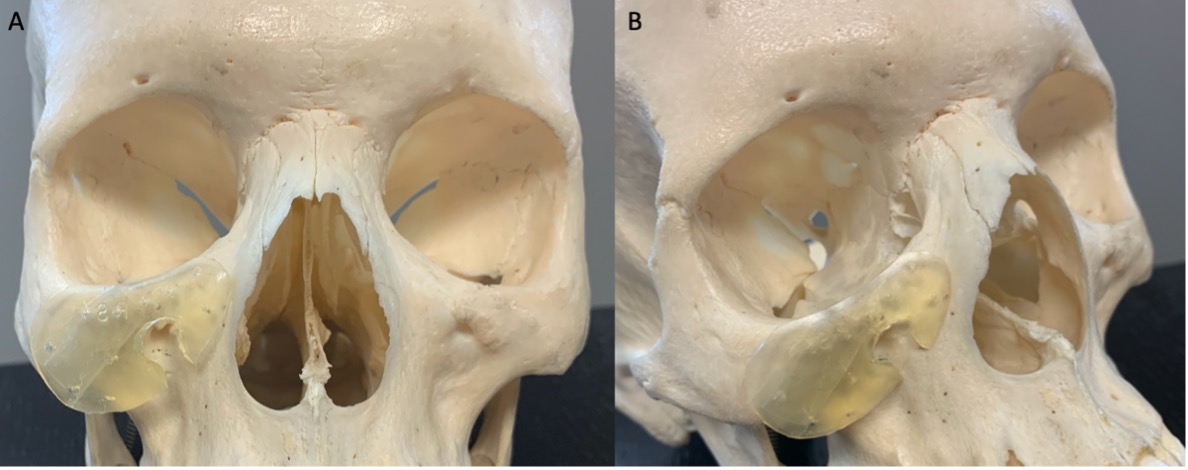

Tear trough implants

- While similar in placement to orbital rim implants, tear trough implants extend more medially and less laterally. They also impart less anterior projection than the orbital rim implants, and are typically made of silicone.

- The goal of this implant is not to improve anterior projection of the inferior orbital rim, but rather to fill in the soft-tissue hollow in the medial 2/3rds of the lower eyelid.

Figure 2. (A and B) Silicone tear trough implant positioned with its superior edge along the inferior orbital rim, with a notch trimmed out to avoid impingement of the infraorbital nerve.

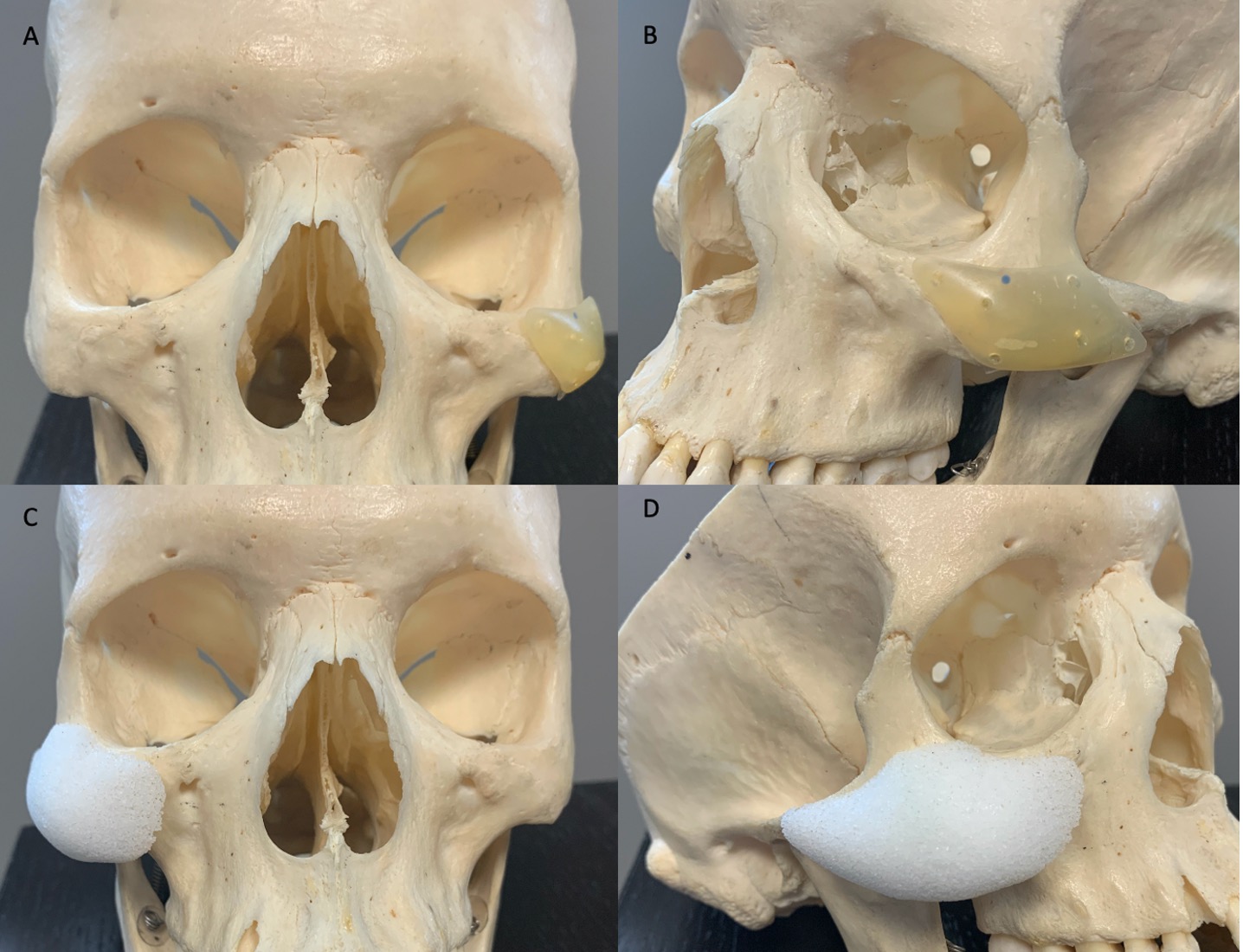

Cheek implants

- Several different designs of cheek implants exist and can be used to augment sub-malar volume, malar volume, or both.

- Extended variations can be used to augment the entire mid-face, from the nasal area to the zygomatic arch.

Figure 3. (A) Silicone malar implant and (B) medpor combined shell, designed to augment both malar and sub-malar volume.

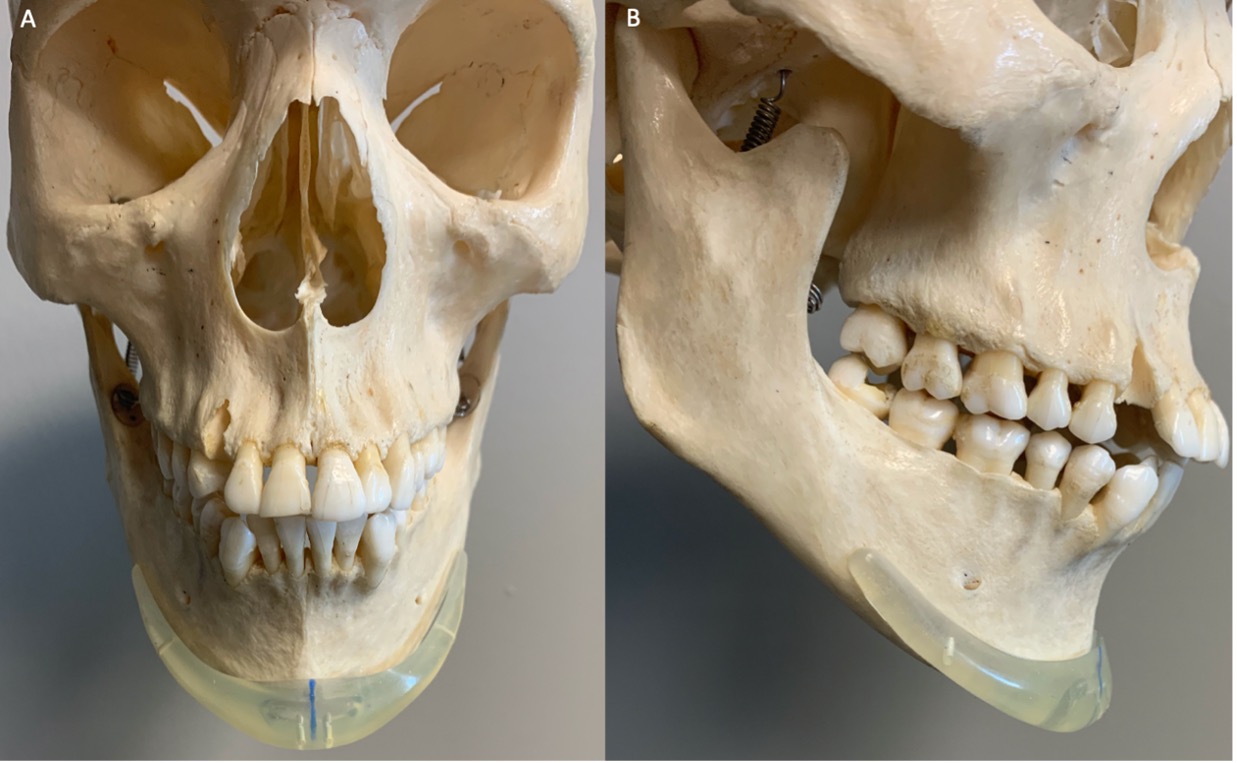

Chin implants

- Chin implants augment the anterior projection of the chin in patients with genial retrusion. They can also augment the vertical dimension of the chin to make the chin appear longer.

- The chin implant is positioned centrally, but various designs extend to the lateral mandible for blending purposes, or further, to the pre-jowl sulcus, to simultaneously address aesthetic concerns in this region.

Figure 4. (A and B) Medium sized silicone chin implant which should be positioned with the blue mark aligned with the center of the patient’s face. The tail of the implant should sit along the inferior border of the mandible, well below the mental foramen.

Mandibular implants

- Mandibular implants can be used to augment the angle and/or projection of the jaw.

- A purely mandibular angle implant increases projection at the angle of the jaw and can also be used to add vertical length for a more defined jawline. A wrap-around version allows augmentation of both the lateral and inferior borders of the mandibular angle. Finally, a lateral augmentation onlay adds volume to the lateral profile of the mandible at the posterior body of the angle.

- Implant selection is based on the type of augmentation desired, including horizontal volume, vertical volume or both.

Temple implants

- Temple implants are intended to be permanent solution to address temporal hollowing

- While hollowing occurs as part of the aging process, it is also encountered frequently following surgical procedures in this region where the temporalis muscle is disinserted and undergoes post-operative atrophy.

- Implant size can be selected depending on the degree of temporal hollowing.

Nasal implants

- A variety of designs exist and can be selected to augment or correct deformities of the nasal dorsum and/or nasal tip cartilage.

- Implants can also be used to widen the nostrils and augment the nasal valve, which serves to prevent collapse of the nostril during inhalation.

Pre-operative evaluation

- Existing facial asymmetries should be evaluated and discussed, and the surgeon should gain a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s goals.

- A thorough pre-operative history should be obtained, specifically including any history of prior craniofacial trauma, previous surgical and non-surgical interventions (including injectable fillers), health of dentition and periodontia (if an oral insertion route is being considered), general health (bleeding dyscrasias, diabetes) and social history (smoking) that are likely to increase the risk of complications (bleeding or infection) or otherwise impair post-operative healing.

- Some surgeons recommend starting oral antibiotics the day prior to surgery, and continuing for a 10-day post-operative course.5

Orbital rim implants

- Patients benefiting from orbital rim implants tend to have a prominent eye with a recessed inferior orbital rim. This is known as a negative vector. These patients often develop inferior scleral show and rounding of the lower eyelid.

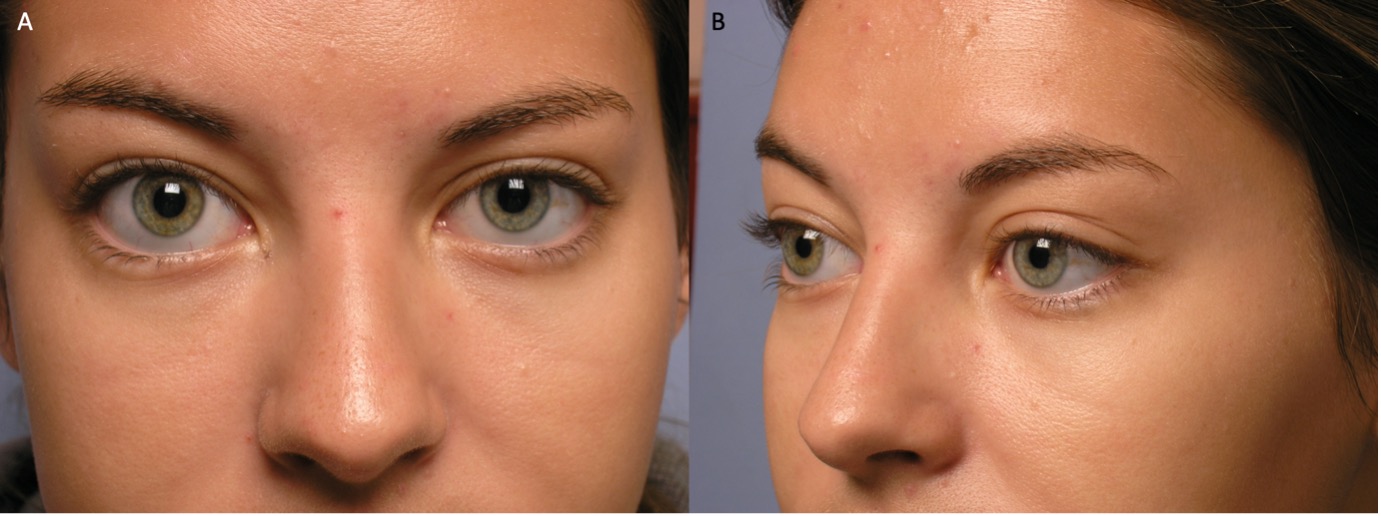

Figure 5. (A and B) A young patient demonstrating features consistent with prominent globe morphology, including inferior scleral show and rounding of the lower eyelid. Laboratory and radiologic work up for possible thyroid eye disease was unremarkable.

Cheek implants

- Evaluation of the patient’s oral health should be performed, as insertion of the implant through an oral incision in the setting of dental or periodontal disease can increase the risk of infection.

- The projection of the central and lateral portions of the mid-face are evaluated to determine which type of implant is indicated.

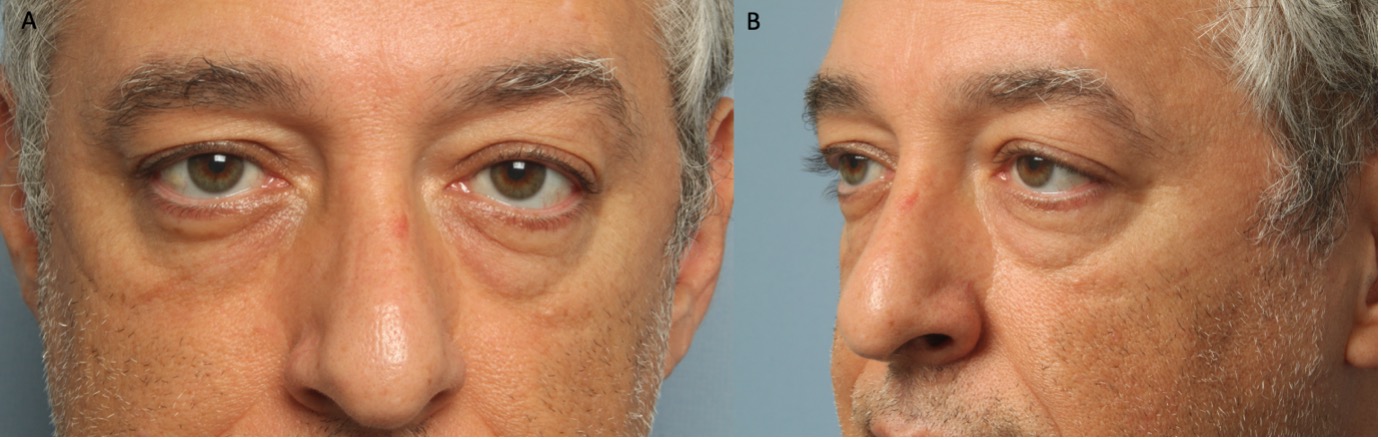

Figure 6. (A and B) A middle-aged patient demonstrating significant descent and deflation of the mid-face. A combined shell style cheek implant would be reasonable to consider in this patient.

Chin implants

- Riedel’s plane can be used to assist in identifying a recessed chin that would benefit from augmentation. In females, it may be appropriate for the chin to fall slightly behind this plane (1-3 mm). In males, more significant chin projection may be desirable, as this imparts a more masculine appearance.

- Patients who would benefit from a chin implant often have an over-bite, and may also have a poorly defined cervicomental angle.

- It is helpful to assess the degree of muscle dimpling. Patients with a recessed chin often retract their mentalis and will have evidence of dimpling on the skin. This may or may not improve following chin augmentation.

- It is necessary to evaluate whether or not the patient has a congenitally hypoplastic mandible and would therefore benefit more from moving the entire jaw forward with a sliding genioplasty.

Figure 7. Riedel’s plane is formed by drawing a line that touches the upper and lower lips. This figure demonstrates 3D photographs of a patient (A) with a recessed chin and (B) following simulated insertion of a large chin implant, which improves the chin projection to within approximately 2mm of Riedel’s plane.

Surgical technique

General considerations

- The shape, contour, and implant material to be used should be selected pre-operatively. Most implants are available in a range of sizes (small, medium, large, extra-large). Some come with sizers that can be inserted at the time of surgery in order to aide selection of the optimal implant size required to achieve the desired outcome.

- Implant insertion can be performed under local, IV sedation or general anesthesia, depending on both patient factors and other planned simultaneous procedures.

- Implants are often soaked in antibiotic solution prior to insertion.

Orbital rim implants

- A swinging eyelid approach is often required to allow for optimal exposure and implant positioning. To achieve this, a lateral canthotomy is performed and the inferior limb of the lateral canthal tendon disinserted. The conjunctiva and lower eyelid retractors are then incised approximately 4mm below the inferior tarsal border.

- A 4-0 silk traction suture may be placed in the lower lid retractors to provide better exposure. The dissection is carried down to the orbital rim in the sub-orbicularis plane using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection.

- Once the arcus marginalis is adequately exposed, it is incised, leaving a 3mm cuff of intact tissue. The implant can later be secured to the cuff of periosteum. The sub-periosteal plane is developed from the frontozygomatic suture to the anterior lacrimal crest. The insertion of the levator labi superioris overlies the infraorbital neurovascular bundle and thus must be disinserted to provide for adequate visualization. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the infraorbital nerve in an effort to prevent post-operative paresthesia.

- After an adequate sub-periosteal pocket has been created, the arcus marginalis can be elevated slightly so that the superior edge of the implant wraps around the orbital rim.

- The implant sits on the inferior orbital rim with slight extension medially towards nose and laterally towards the body of the zygoma. The implant can be trimmed to optimize the desired augmentation.

- Porous implants can be secured by one- or two-point screw fixation. Silicone implants can be secured to the remaining rim of arcus marginalis with permanent or dissolvable sutures. A sub-orbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) lift can be performed to augment the midface elevation, particularly in cases where there is deficient anterior lamella.

- The canthal tendon is then reconstructed and the conjunctival incision is closed.

Tear trough implants

- Tear trough implants can often be inserted through a trans-conjunctival approach alone, however if intraoperative exposure is limited, a swinging eyelid approach can be utilized.

- Surgical dissection is similar to the approach described above for orbital rim implant insertion.

- The implant is typically secured with sutures to the arcus marginalis.

Cheek implants

- Cheek implants are placed in the sub-periosteal plane of the mid-face. It is critical to ensure that they are inserted into the sub-periosteal plane in order to avoid injury to the mimetic muscles and the facial nerves.

- A horizontal incision is made 10 – 15 mm above the canine tooth and carried down to the periosteal level. The periosteum is then incised and elevated as dissection is carried superiorly along the anterior wall of the maxilla and laterally to expose the medial portion of the zygomatic arch. The sub-periosteal pocket should be large enough to comfortably accommodate the implant, but not so large as to allow undesired mobility of the implant in the early post-operative period.

- Implant sizers can be inserted to aide in selecting the optimal size of implant, and consideration can be given to irrigating the surgical field with antibiotic solution.

- Once the implant itself has been inserted, care should be taken to ensure that the entire implant is sitting flush with the bone, and that there is no portion that is inadvertently folded up or down.

- After the implant is placed in the pocket, the cheeks and lips can be manipulated to simulate facial animation. If this results in displacement from the incision pocket, the implant should be trimmed to optimize fit.

- In some instances, no additional fixation is required (the implant is well-conforming and in a tight sub-periosteal pocket, showing minimal movement with manipulation of the overlying soft tissues intraoperatively); however, fixation with a single screw can improve the predictability of post-operative outcomes by further diminishing the risk of implant migration. Optimal regions for screw fixation include the lateral buttress or lateral piriform aperture, as the bone is relatively thick in both of these locations.

- In order to achieve symmetric implant placement, it can be useful to measure the distance from various anatomical landmarks, such as the infraorbital foramen, to the implant and to ensure that these are similar on both sides.

- The wound can be irrigated with antibiotic solution at this point

- Closure of the mucosa is achieved with interrupted 4-0 chromic sutures. The closure of the incision should not be water-tight as this can lead to a hematoma or seroma.

- Post-operatively, antibacterial mouthwashes can be used for the first week after surgery.

Chin implants

- The patient’s midline can be marked in the pre-operative area while they are in an upright position to ensure optimal centration of the implant intraoperatively.

- Implants can be inserted via either an intra-oral or an extra-oral (cutaneous incision in the submental area) route.

- When proceeding via an intra-oral route, some prefer to make a hinged incision whereby the mucous membrane of the lower lip is incised approximately 15mm anterior to the mandibular sulcus. Once the mucosa and orbicularis oris are incised, dissection is carried posteriorly towards the mandible. The mentalis muscles are transected near their periosteal origin, exposing the periosteum for subsequent sub-periosteal dissection. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the mental neurovascular bundles, which lie 12-15 mm superior to the inferior mandibular border.

- Alternatively, a submental transcutaneous approach can be taken, particularly when a submental incision is required for other simultaneous procedures addressing the neck. This incision is typically placed at the submental crease or slightly behind it. Dissection can be carried straight down to the periosteum at the inferior border of the mandible in the midline, and then a sub-periosteal pocket is created to appropriately fit the implant, remaining cognisant of the location of the mental foramen.

- Once an adequate sub-periosteal pocked has been created, the implant can be selected and trimmed to optimize fit and projection. The implant is ideally positioned low, on the thick central mandibular bone with the tails below the mental foramen and neurovascular bundles. A general rule of thumb is to align the inferior border of the implant flush with the inferior edge of the mandible.

- Consideration can then be given to fixating the implant.

- The transected mentalis muscles should be re-approximated. If an intra-oral approach was used, the mucosa is then closed in a bi-layered fashion. Similarly, a bi- or tri- layer closure of the cutaneous incision (periosteum, sub-cutaneous tissue, skin) should be performed if a trans-cutaneous approach was utilized.

- A compression dressing can be applied at the end of the case

Temporal implants

- An incision is made posterior to the hairline and dissection is then carried down to the temporalis fossa.

- A parallel incision is made in the fascia, and a periosteal elevator can be used to elevate the fascia off the muscle over the entire temple region.

- The implant is then inserted into this pocked and can be fixated to the temporalis fascia with a suture.

Post-operative management

- Pre-, intra- and post-operative antibiotics are recommended by many surgeons, although rigorous scientific evidence is lacking due to the relatively low incidence of post-operative infection, particularly of non-porous implants (<1%).1

- When implants are inserted via an intra-oral incision, chlorhexidine mouth washes can be used after meals for 2 weeks.

- Cool compresses in the first 72 hours

- Consider post-operative steroids if significant swelling

- Following insertion of cheek implants, a liquid or soft diet is often recommended for the first 48 hours. Patients should also be advised to avoid excessive facial animation for the first 2-3 days.

- Compression dressings may be useful in the early post-operative period to decrease the risk of seroma/hematoma formation and minimize post-operative edema

Complications

- Temporary paresthesia and moderate swelling post-operatively can be expected. Permanent numbness is rare. If numbness of the lower lip persists for more than one week following insertion of a chin implant, exploration to confirm that the implant is not impinging on the mental nerves may be indicated. Numbness of the upper lip and teeth, or shooting pain in this region, is indicative of infraorbital neuropathy and also may require exploration if it persists beyond one week.

- Damage to the facial nerve uncommon, but possible.

- Formation of a hematoma or seroma surrounding the implant

- Implant infection can arise in the early post-operative period or several years later. The patient should be started on antibiotics, which might salvage the implant; however, in most instances, the implant must be removed.10 There is some evidence to suggest that the risk of infection is higher with porous implant materials.1

- Implant migration or extrusion

- Asymmetry

- Over- or under-correction: Many recommend waiting 6 weeks prior to exchanging the implant, as it can be difficult to assess the final outcome earlier than this.

- Resorption of underlying bone can occur; however, newer implant designs aim to distribute pressure over a greater anatomic surface area with the goal of reducing the risk of significant bone resorption.

References

- Oliver JD, Eells AC, Saba ES, et al. Alloplastic Facial Implants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Outcomes and Uses in Aesthetic and Reconstructive Plastic Surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(3):625-636.

- Gupta N, Wulu J, Spiegel JH. Safety of Combined Facial Plastic Procedures Affecting Multiple Planes in a Single Setting in Facial Feminization for Transgender Patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(4):993-999.

- Morrison SD, Satterwhite T. Lower Jaw Recontouring in Facial Gender-Affirming Surgery. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019;27(2):233-242.

- Kridel RWH, Patel S. Cheek and Chin Implants to Enhance Facelift Results. Facial Plast Surg. 2017;33(3):279-284.

- Floyd EM, Eppley B, Perkins SW. Postoperative Care in Facial Implants. Facial Plast Surg. 2018;34(6):612-623.

- Copperman TS, Idowu OO, Jalaj S, et al. Patient-Specific Implants in Oculofacial Plastic Surgery. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020.

- Weinberg DA, Goldberg RA, Hoenig J, Shorr N, Baylis HI. Management of relative proptosis with a porous polyethylene orbital rim onlay implant. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;15(1):67-73.

- Goldberg RA, Soroudi AE, McCann JD. Treatment of prominent eyes with orbital rim onlay implants: four-year experience. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19(1):38-45.

- Steinsapir KD. Aesthetic and restorative midface lifting with hand-carved, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene orbital rim implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(5):1727-1737; discussion 1738-1741.

- Rayess HM, Svider P, Hanba C, Patel VS, Carron M, Zuliani G. Adverse Events in Facial Implant Surgery and Associated Malpractice Litigation. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2018;20(3):244-248.