Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Eyelid

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- The pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) differs at various anatomic sites based on unique oncogenetic pressures prevalent at that site.

- SCC in the eyelid seems primarily related to sun exposure, similar to neoplastic transformation in SCC of the conjunctiva.

- Ultraviolet radiation exposure might interact synergistically with cutaneous human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and SCC of the skin (Iannacone 2012).

- In a case control study of 156 cutaneous SCC patients, both sensitivity to sunlight and poor tanning, and seropositivity for HPV infection, increased the risk of SCC.

- However, sun exposure is likely a more critical etiologic factor.

- Precancerous lesions include actinic keratoses, which are keratinocyte derived and found predominantly in fair skinned individuals and on-sun exposed surfaces.

- Multistep carcinogenesis is the generally accepted model for SCC, likely beginning with mutation in a tumor suppressor, leading to genetic instability and the emergence of driver oncogenes (Ratushny 2012).

- Initial genomic instability in keratinocytes likely results from ultraviolet beta ray induced inactivation of p53.

- About 58% of cutaneous SCCs harbor UVB signature mutations such as CC→TT and C→T transitions (Brash 1991).

- Activating RAS, particularly Hras (Harvey rat sarcoma virus oncogene), is among candidate oncogene mutations that promote cutaneous SCC formation (Boukamp 2005).

- Aberrant ras activation promotes mitogenesis, resistance to apoptosis and angiogenesis.

- Tumor formation by human keratinocytes transformed through retrovirally mediated expression of HRAS is inhibited with blocking antibodies to laminin 332, a component of the basement membrane, and α6β4 integrin, one of its ligation partners.

- External environment controls are important mediators of cell growth and loss of control is involved in tumor progression.

- Epidermal stem cells are the putative cells of origin of cutaneous SCC.

Epidemiology

- Prevalence varies based on factors that include relative sun exposure.

- In a 10-year review of 100 periocular malignancies at a tertiary care hospital in Tehran, Iran, BCC represented 83%, SCC 8% and sebaceous carcinoma 6% (Bagheri 2013).

- The incidence of SCC in Peshawar, Pakistan, was even higher, among 222 malignant eyelid tumors 2007–2010: BCC 59%, SCC 31%, sebaceous carcinoma 7%, melanoma and others 2% (Hussain 2013).

- In Singapore, sebaceous carcinoma was relatively more common: BCC 82%, sebaceous carcinoma 11%, SCC 4% (Lim VS 2012).

- In Hong Kong, similar incidences were reported: BCC 75%, sebaceous carcinoma 11%, SCC 5% (Mak 2011).

- In Taiwan, among 1121 eyelid malignancies reported between 1979 and 1999, the mean age at diagnosis was 62.6±14.1 years, with BCC representing 65%, SCC 12% and sebaceous carcinoma 8% (Lin 2006).

- In an Olmstead County, Minnesota, retrospective survey of 174 malignant eyelid tumors from 1976 to 1990, 91% were BCC and 8% were SCC and no cases of sebaceous carcinoma were identified (Cook 1999).

- An unusual distribution of histopathology has been reported among 178 eyelid malignancies in New Delhi, India from 1982-1992, with an almost equal incidence of sebaceous carcinoma (32%), BCC (30%) and SCC (28%) (Sihota 1996).

- In Australia, where a fair-skinned population is exposed to a relatively high degree of sun exposure, the prevalence of periocular SCC is particularly high.

- In 79 periocular SCCs recorded in the Australian Mohs Database between 1993 and 1999, 68% were lower eyelid, 24% were medial canthus and 7% were upper eyelid, as expected based on angle to the sun (Malhotra 2004).

- In that group, among 73% primary tumors and 27% recurrent tumors, 49% were well differentiated, and 35% were moderately differentiated.

- Perineural invasion was seen in only 3 cases (2 recurrent and 1 primary) suggesting that this is a relatively late event in periocular SCC tumor progression.

- In a study of 111 patients treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center from 1952 to 2000, 24% had regional nodal metastasis, and 6% had distant metastasis (Faustina 2004).

- These unusually high percentages reflect the tertiary referral patterns of a cancer center.

- In an older study of periocular eyelid malignancies, the diagnosis of SCC was changed in 18 of 49 tumors to another diagnosis, including sebaceous gland carcinoma (10), basal cell carcinoma (4), papilloma (1) and keratosis (3) (Doxanas 1987).

- Among 648 eyelid malignancies diagnosed at the Wills Eye Hospital from 1978 to 1987, 24 (3.7%) were SCC; age range was 55–96 years (median 72 years) (Dailey 1994).

History

- It is helpful to define the relative degree to which the patient was exposed to unprotected ultraviolet irradiation.

- Occupational history

- Military history

- Social history — where the patient lived, favorite recreational activities

- Medical history — is there a history of radiation for inflammatory (acne) or malignant skin conditions?

- A history of previous skin cancer might suggest recurrence and more extensive local progression.

- Current lesion — duration, change in appearance, rate of growth, prior biopsy, inflammation, bleeding

- History of pre-existing lesion such as actinic keratosis, Bowen disease, radiation dermatoses, burn scars, and inflammatory lesions

- Prior lesions removed or “burned off” without pathologic diagnosis

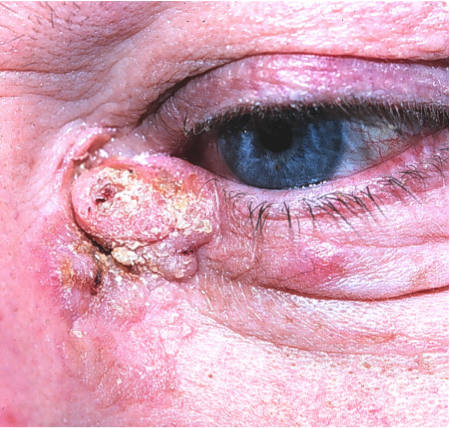

Clinical features (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

- Hyperkeratotic macular (flat) or nodular (elevated) skin lesion

- Can have significant inflammatory component

- Later phases can have ulceration.

- Associated sun-damaged skin

- Loss of normal eyelid architecture (i.e., loss of lashes, eyelid margin distortion)

- Regional lymphadenopathy

- Recurrent bleeding or scabbing episodes

Testing

- Incisional or excisional biopsy depending on clinical presentation

- Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with enhancement if intraorbital or intracranial spread is suspected

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

- The Seventh Edition AJCC definition for eyelid carcinoma:

- T1 = tumor ≤ 5 mm, not invading tarsus or lid margin

- T2a = tumor > 5 mm, < 10 mm, or any tumor invading tarsus or lid margin

- T2b = tumor > 10 mm, < 20 mm, or any tumor involving full thickness eyelid

- T3a = tumor > 20 mm, or any tumor invading adjacent ocular structure or orbit, or perineural invasion

- T3b = complete tumor resection requires enucleation, exenteration or bone removal

- T4 = tumor not resectable

- cN0 = no regional lymph nodes, based on exam and imaging

- pN0 = no regional lymph nodes, based on biopsy

- M0 = no distant metastasis

- M1 = distant metastasis

- There have been no studies of prognosis based on staging for eyelid SCC.

Figure 1. Image courtesy Navdeep Nijhawan, MD.

Figure 2. Image courtesy Mark. J. Lucarelli, MD, FACS.

Risk factors

- Sun exposure

- Previous skin cancer

- Previous irradiation

- Psoralen therapy

- Human papillomavirus

Differential diagnosis

- Basal cell carcinoma — nodular, morpheaform (sclerosing)

- Actinic keratosis

- Chronic inflammatory blepharitis

- Keratoacanthoma (considered to be a low-grade squamous-cell carcinoma)

- Papilloma

- Sebaceous carcinoma

- Nonspecific, chronic dermatitis

- Inverted follicular keratosis

- Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia

- Amelanotic melanoma

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Spontaneous resolution is not observed with this tumor.

- There is no role for observation once the diagnosis has been made.

- It might be worth confirming the diagnosis before intervening surgically because of the many simulating lesions.

Medical therapy

- Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), also known as HER1 or Erb1 is a transmembrane receptor protein with multiple ligands including epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor alpha.

- Activation of EGFR in keratinocytes results in proliferation, migration and resistance to apoptosis, and overexpression has been implicated in carcinogenesis at a number of sites including mucosal and cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck.

- EGFR overexpression correlates with aggressiveness of disease and EGFR inhibition has been studied for SCC using tyrosine kinase inhibitors (gefitinib and erlotinib) and monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab) (Yin 2013). These drugs are not FDA-approved for eyelid SCC.

- PD-1 inhibitors are checkpoint inhibitors that have been used in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic disease

- Systemic chemotherapy is reserved for unresectable disease or distant metastasis.

Radiation

- External beam radiotherapy is recommended for patients with evidence of perineural invasion (Bowyer 2003).

- Doses range from 50 to 90 gray with a mean of 60 gray.

- The target field can include the forehead, cheek, and cavernous sinus.

- When perineural invasion involves the facial nerve, the target field can also include the parotid gland and neck.

Surgery

- Incisional biopsy

- Treatment of choice is total excision of the lesion with either intraoperative frozen section tumor margin control or Mohs micrographic surgery.

- Reconstruction to re-establish function and aesthetics

Other management considerations

- Cryotherapy is available as adjuvant treatment after surgery and for individuals who refuse surgery or are poor surgical candidates

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy may detect regional spread of disease. Theoretically, this detection should facilitate better treatment. However, the current literature does not show a clear survival benefit.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

- After complete surgical resection confirmed by intraoperative margin control, consider annual follow-up to assess recurrence or the development of other lesions.

- Adjacent areas that feature unsatisfactory healing or new suspicious masses should be biopsied.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Eyelid/facial dysfunction with ocular surface compromise or other ocular/facial functional compromise (tearing, diplopia, ptosis, lagophthalmos, cicatricial eyelid ectropion/retraction)

- Radiation to the orbit might cause ischemia, necrosis, erythema, edema and chronic discharge.

- Unacceptable eyelid/facial aesthetic result

Disease-related complications

- In a study of 21 cases of perineural spread of cutaneous SCC via the orbit, the forehead and eyebrow were the most common sites of the primary lesion (McNab 1997) (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Forehead and eyebrow lesion, which has a high likelihood of perineural invasion, especially because the surrounding tissues show evidence of prior surgery and this is likely a recurrent tumor.

- 9 presented with pain, 20 had altered sensory nerve function, 14 had ophthalmoplegia, and 14 had evidence of facial nerve dysfunction.

- 14 of these patients died of disease within 9 months to 5 years after recognition of perineural invasion.

- Direct tumor extension into orbit with functional compromise (vision loss, diplopia, pain)

- Tumor board review (if available) might be helpful in determining subsequent medical or surgical therapies.

- Direct tumor extension in adjacent facial tissues such as the lacrimal drainage system

- Regional metastasis

Historical perspective

- In 1902, roentgen-induced SCC was first reported by Frieben soon after the discovery of x-rays.

- In 1902, Krompecher distinguished between basal cell carcinoma and SCC (Reifler 1986).

- In 1963, Lorenz Zimmerman wrote that “in the past decade new concepts in dermal pathology have developed regarding many lesions that had formerly been interpreted clinically as squamous cell carcinoma.” (Kwitko 1963).

- Among 1,176 eyelid lesions studied at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology from 1955-1959, 550 were malignant, of which 91% were basal cell carcinomas.

- Of 115 lesions that had been diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma, only 12 were considered squamous cell carcinomas on review.

- Among the tumors previously confused with SCC were keratoacanthoma (Boniuk 1967) and inverted follicular keratosis (Boniuk 1963).

References and additional resources

- Basic and Clinical Sciences Course, Section 4: Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors; Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System, 2013–2014. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Ophthalmology Monographs 8. Surgery of the Eyelid, Orbit & Lacrimal system, 1, 1993. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Focal Points: Periorbital Skin Cancers: The Dermatologist’s Perspective, Module 1, 2006. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Bagheri A, Tavakoli M, Kanaani A, et al. Eyelid masses: a 10-year survey from a tertiary eye hospital in Tehran. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20(3):187-192.

- Boniuk M, Zimmerman LE. Eyelid tumors with reference to lesions confused with squamous cell carcinoma. II. Inverted follicular keratosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;69:698-707.

- Boniuk M, Zimmerman LE. Eyelid tumors with reference to lesions confused with squamous cell carcinoma. 3. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;77(1):29-40.

- Boukamp P. Non-melanoma skin cancer: what drives tumor development and progression? 2005;26:1657-1667.

- Bowyer JD, Sullivan TJ, Whitehead KJ, Kelly LE, Allison RW. The management of perineural spread of squamous cell carcinoma to the ocular adnexae. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;19(4):275-281.

- Brash DE, Rudolph JA, Simon JA, et al. A role for sunlight in skin cancer: UV-induced p53 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(22):10124-10128.

- Cook BE Jr, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(4):746-750.

- Dailey JR, Kennedy RH, Flaharty PM, Eagle RC Jr, Flanagan JC. Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;10(3):153-159.

- Doxanas MT, Iliff WJ, Iliff NT, Green WR. Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1987;94(5):538-541.

- Faustina M, Diba R, Ahmadi MA, Esmaeli B. Patterns of regional and distant metastasis in patients with eyelid and periocular squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(10):1930-1932.

- Frichen A. Cancroid des rechten Handruckens nach Langdauender Einwirkung von Rontgenstrahlen. Fartuch Roentgenstr. 1902;6:106.

- Hussain I, Khan FM, Alam M, Khan BS. Clinicopathological analysis of malignant eyelid tumours in north-west Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63(1):25-27.

- Iannacone MR, Wang W, Stockwell HG, et al. Sunlight exposure and cutaneous human papillomavirus seroreactivity in basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(3):399-406.

- Kwitko ML, Boniuk M, Zimmerman LE. Eyelid tumors with reference to lesions confused with squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;69(6):693-697.

- Lin HY, Cheng CY, Hsu WM, Kao WH, Chou P. Incidence of eyelid cancers in Taiwan: a 21-year review. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(11):2101-2107.

- Mak ST, Wong AC, Io IY, Tse RK. Malignant eyelid tumors in Hong Kong 1997-2009. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2011;55(6):681-685.

- Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, Selva D. The Australian Mohs database: periocular squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(4):617-623.

- McNab AA, Francis IC, Benger R, Crompton JL. Perineural spread of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma via the orbit. Clinical features and outcome in 21 cases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(9):1457-1462.

- Ratushny V, Gober MD, Hick R, et al. From keratinocyte to cancer: the pathogenesis and modeling of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Investig. 2012;122:464.

- Reifler DM, Hornblass A.Surv Ophthalmol. Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid. 1986;30(6):349-365.

- Sihota R, Tandon K, Betharia SM, Arora R. Malignant eyelid tumors in an Indian population. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114(1):108-109.

- Yin VT, Pfeiffer ML, Esmaeli B. Targeted therapy for orbital and periocular basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29(2):87-92.

- Freitag SK, Aakalu V, Tao JP, et al. Ophthalmic Technology Assessment – Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Eyelid and Conjunctival Malignancy: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology, 2020, epub ahead of print.