Basal Cell Carcinoma

Updated August 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Clinical recognition confirmed by biopsy and histopathologic exam

Etiology

- Primarily UV (especially 290–320 nm ultraviolet B) and sun exposure

- Ultraviolet spectrum is divided into three regions: UVA (320–400 nm), UVB (280–320 nm), and UVC (200–280 nm).

- UVB is primary cause of erythema after sun exposure and sunburn.

- UVB most closely associated with BCC and is also the primary cause of skin aging changes.

- UVA is associated with skin sensitivity from sulfonamides, phenothiazines, psoralens (PUVA therapy).

- UVC is absorbed by the atmosphere ozone layer.

- Intense intermittent (sporadic, particularly by indoor workers) recreational sun exposure is associated with melanoma and BCC, chronic occupational sun exposure associated with SCC (Zanetti 2006).

- Relative sun exposure at different sites was compared with the relative incidence of periocular BCC — correlation was poor suggesting alternative etiologic factors.

- Sun sensitive skin — BCC patients report being more prone to sunburn (pain and/or blistering lasting 2 or more days) after first hour of sun exposure.

- Early age UV exposure — meta-analysis of 9,328 nonmelanoma skin cancers, showed indoor tanning a risk when exposure is before age 25 (Wehner 2012).

- Red hair is risk factor and for multiple BCCs (Kiiski 2010).

- Blond hair, freckles and extremity moles (Wu 2013)

- Lightly pigmented iris, correlates with light pigmentation

- Family history of melanoma is a risk factor for BCC (Wu 2013).

- Cumulative UV exposure might not be a risk factor — time spent outdoors, in summer, not consistently significant in case control studies (Karagas 2014).

- Cigarette smoking is not associated with eyelid BCC (Wojno 1999), but does increase risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (Leonardi-Bee 2012).

- Chronic human papillomavirus infection not associated with BCC, does increase the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (Karagas 2010).

Epidemiology

- According to the American Cancer Society BCC accounts for half of all cancers in the US (Rubin 2005).

- More than one million cases annually in the US (Cancer Facts and Figures, American Cancer Society).

- Australia has the highest incidence of BCC in the world.

- Men and women are equally affected (Cook 1999).

- Correlation with latitude is stronger for SCC than BCC.

- Reported increase in incidence of BCC might be due to improved surveillance.

- Among malignant eyelid tumors in Olmstead County from 1976 to 1990, BCCs accounted for 90% (Cook 1999).

- Age and gender adjusted incidence was 14.4 BCC per 100,000 individuals per year.

- Most national registries in the US do not collect information on BCC, so epidemiologic data on BCC in general is limited (Wu 2013).

History

- Nodule

- Ulceration

- Growth

- Erythema

- Bleeding

- Persistence

- Progression

- Prior skin lesions

Clinical features

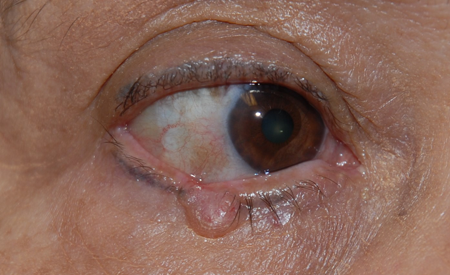

- Nodular lesion is a pearly papule, often with central ulceration (noduloulcerative BCC), madarosis and loss of normal tissue architecture, with overlying telangiectasia and rolled border (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nodular basal cell.

- Morpheaform lesion is an indurated scar-like plaque with indistinct margins.

- At lid margin, mostly arise in anterior lamella, BCC is rarely seen on nonhair-bearing surfaces such as palms and soles.

- At clinical margins, tumor can be circumscribed or infiltrative

- Morpheaform spreads beneath epithelium, nodular spread is more superficial.

- Pigmented BCCs (Figure 2) are rare, and behavior is similar to other BCC (Kirzhner 2012).

Figure 2. Pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

- Metastasis from BCC is possible, though very rare, with a median interval from presentation to metastasis of 9 years.

- Metastasis is to regional lymph nodes, followed by bone, liver, and lung.

- Prognosis with metastatic disease is poor with mean survival ranging from 8 months to 3.6 years (Walling 2004).

- Primary BCC on the caruncle (Mejer 1998) has been reported in 9 cases (Ugurlu 2014).

- Intraocular invasion by periocular BCC has been reported in a patient with lepromatous leprosy (Aldred 1980).

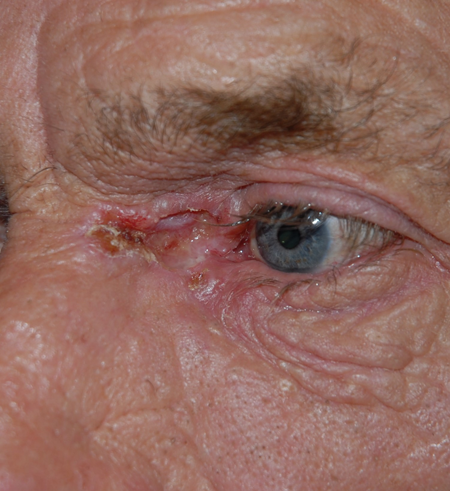

- Orbital invasion especially with recurrent medial canthal lesions (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Deep medial canthal basal cell carcinoma.

- Recurrent tumor can be evident beneath the conjunctiva without recurrent skin involvement (Lee 2010).

- Vigilant histopathologic evaluation of all lesions removed from the eyelid is important.

- A 28-year-old man underwent excision of a presumed upper lid margin wart, without histopathologic evaluation, which actually harbored a BCC.

- He developed and died of intracranial extension 7 years later (Moro 1998).

Testing

- Biopsy — histopathology

- Oval nuclei

- Scant cytoplasm

- Cells resemble basal cells of epidermis

- Rarely display anaplasia

- First project into upper dermis

- Palisading = tumor cells at periphery arranged in radial pattern

- Abundant collagen in stroma is typical of morpheaform

- Lacunae = islands of tumor cells retract from stroma

- Desmosomal and hemidesmosomal attachments are present, but reduced in number

- Necrosis is common

- Morpheaform BCC has elongated strands of infiltrating tumor, several cell layers thick

- Superficial spreading tumors can have deeper tumor buds extending into the dermis.

- Palisading cells push their way into surrounding and infiltrate less

- Basosquamous tumors have squamous differentiation — might be more likely to recur

Risk factors

- Unusual risk factors — Among solid-organ transplant recipients, risk of SCC is 65 to 250 times higher, and risk of BCC is 10 times higher than general population (Jensen 1999).

- Xeroderma pigmentosum — extremely rare, autosomal recessive, multiple cutaneous malignancies including BCC, develop at an early age, inability to repair DNA damage from UVB.

- One case described, had 166 BCCs over 16 years (Ramkumar 2011), with no SCCs or melanomas.

- That patient died from progressive neurologic degeneration with loss of hearing, inability to walk, difficulty swallowing, and global cerebral atrophy.

- A second described patient with early sun protection was spared skin tumors, but died of neurologic degeneration with hearing loss, areflexia, ataxia, and decreased vision.

- In a larger study of 27 patients with xeroderma pigmentosum from Saudi Arabia, the gender distribution was equal (14 males).

- History of consanguinity was present in one third of the patients.

- Eyelid BCC developed in four patients (Alfawaz 2011).

- Cockayne syndrome is similarly caused by defect in nucleotide excision and DNA repair, causes vision loss and neurologic degeneration.

- Genetic syndromes associated with BCC risk (cancer.gov).

- Basal cell nevus syndrome — see separate outline.

- Bazex-Dupre-Christol syndrome — X-linked autosomal dominant; congenital hypotrichosis; follicular atrophoderma on dorsal hands, feet, face, elbows, knees; chromosomal locus Xq24-q27.

- Brooke-Spiegler syndrome — autosomal dominant; multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas and spiradenomas, in head and neck, appear in early childhood, gradually increase in number and size; chromosomal locus 16q12-q13 — can predispose to and/or mimic BCC (Hester 2013).

- Exposure to ultraviolet light

Differential diagnosis

Simulating lesions are important to recognize:

- Trichoepithelioma — benign, usually multiple, dome shaped, can have telangiectasia

- Histologically similar with islands of palisading basaloid cells

- Clinically the lesion do not disrupt surrounding tissues

- Histologically the palisading islands do not infiltrate or distort

- Sebaceous carcinoma

- Origin is posterior lamella, mostly meibomian glands,

- Spreads earlier posteriorly onto conjunctiva

- Oil red-O stain for lipid

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- SCC more commonly arises from precursor lesion

- Faster growth

- Ill-defined borders

- Syringoma

- Nevus

- Marginal chalazion

- Seborrheic keratosis

- Actinic keratosis

- Papilloma

- Apocrine hydrocystoma

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Local slow growth is typical, can be more infiltrative or nodular and ulcerative, depending on histopathologic variant.

- Metastasis is rare — BCC has an unusual dependence on stroma for evolution and progression

- In animal models, stromal alteration precedes tumor.

- Transplantation of tumor is difficult without stroma.

- Limits spread beyond local stroma.

Medical therapy

- Imiquimod 5% cream (Aldara, 3M Pharmaceuticals, Minneapolis, Minnesota) can be used for small nodular tumors (Blasi 2005).

- Use of imiquimod for BCC on the eyelid is off-label and not FDA approved.

- Since 2004, in addition to FDA approval of imiquimod for actinic keratosis and external genital warts, approval was added for treatment of small (less than 2.0 cm in diameter), primary superficial BCC on the trunk, neck, or limbs of an adult with normal immune function.

- Since chances of cure are higher with surgery, indication is cases in which surgery is less indicated than medical therapy (cancer.gov).

- Approval was based on short term double blind controlled studies — among 365 patients, 75% of treated patients had no evidence of disease, clinically or on repeat biopsy, after twelve weeks (Geisse 2004).

- In a long term study of 182 patients, 79% had no evidence of recurrence at two years.

- In ten eyelid margin nodular tumors, ranging in size from 5 x 5 mm to 27 x 10 mm, treated once a day, five times per week, for 8 to 16 weeks, 80% resolved clinically and histologically (Carneiro 2010).

- The patient can apply cream in the morning, left in place for 8 hours, applied 5 days per week for at least 6 weeks, avoiding contact with the eye.

- Fifteen eyelid BCCs were treated with imiquimod daily, five days/weeks, for six weeks, and all showed histopathologic remission within three months, sustained for 24 months (Garcia-Martin 2011).

- Nodular lid margin BCC might need to be treated longer than the standard 6 weeks because it is thicker than typical superficial BCC.

- Twice daily dosing is limited by inflammation.

- Anecdotal opinion from dermatologists is that a stronger inflammatory response is more closely associated with remission.

- Can be more of a problem with thin eyelid skin and tumors adjacent to lid margin.

- Imiquimod’s exact mechanism of action is not known.

- Acts through Toll-like receptor 7 to activate monocytes in antigen presentation, stimulating cytokine mediated tumor suppression.

- Side effects when treating eyelid tumors include keratitis and conjunctivitis.

- Photodynamic therapy is an alternative for lid margin BCC.

- A photosensitizing agent, methyl aminolevulinate is applied topically to lesion and surrounding 4-5 mm.

- Covered with aluminum foil and occlusive dressing for four hours.

- Uses an 80-Joule light-emitting diode light source (632 nm) illuminated for 8 minutes — eye is protected by metallic shield or Frost suture lid closure.

- Requires two photodynamic therapy sessions separated by a week.

- In a study of 16 BCCs treated with this technique complete clinical recovery was observed after 5-year follow-up in 13 patients (82%) (Puccioni 2009).

- Two patients did not respond at all to treatment and 1 patient presented with recurrence after 3 years of tumor-free follow-up.

- Vismodegib and Sonidegib (Odomzo, Sun Pharmaceuticals) are inhibitors of the hedgehog pathway.

- Inappropriate activation of the hedgehog (HH) signaling pathway is found in sporadic and familial cases of BCC (Rubin 2005).

- HH protein binds to tumor-suppressor protein patched homologue 1 (PTCH1).

- PTCH1 suppresses G-protein coupled, transmembrane receptor smoothened (SMO).

- SMO regulates a family of (GL1) transcription factors — in the absence of PTCH1, SMO is constitutively active resulting in continuous activation of target genes.

- In addition, mutations in p-53 tumor-suppressor gene is found in 50% of sporadic BCC mostly C ÚT and CC Ú

- FDA approved for metastatic BCC and recurrent locally invasive disease and nonsurgical candidates.

- Tumors with orbital invasion can be treated with vismodegib to shrink tumor pre-operatively, facilitating surgical excision (Kahana 2013).

- Vismodegib is an oral medication, dose is 150 mg/day.

- Side effects include muscle spasms, hair loss, nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, dysageusia, loss of appetite.

- Sonidegib is an oral medication, dose is 200mg/day.

Radiation

- Can be primary modality for smaller tumors —34–65 Gy in fractionated doses of 2.5–6.5 Gy with shielding of globe

- Treated clinically, tumor-free margin can be relatively small (1 mm) or large (1 cm).

- Morpheaform type can be relatively radioresistant.

- Complications from radiotherapy include:

- Lash loss

- Dry eyes

- Keratopathy

- Skin atrophy and necrosis

- Chronic dermatitis

- Orbital radiotherapy might be appropriate after exenteration if surgical margins are not tumor free.

Surgery

- Mohs’ micrographic surgery — see separate outline

- Studies have shown that even with incomplete excision of a head and neck BCC about 20% do not recur.

- One theory is that even with apparent incomplete excision, the tumor has been completely excised

- Processing error might be responsible, surgeon excising adequate margin, but pathologist not studying true margin.

- Another theory is that BCC induces an immune response which can control or eradicate residual tumor.

- Another theory is that BCC natural history can be slow growth and follow-up in those studies is inadequate.

- Surgeon should be aware of pathologist’s technique in studying tumor margin.

- The expected degree of subclinical spread dictates the appropriate tumor free surgical margin.

- In one study, 98% of BCCs 2 cm in diameter or less were adequately excised by a 4-mm margin (Wolf 1987).

- Subclinical extension in 138 nodular BCCs averaged 2.1 mm (Hamada, 2005).

- That study suggests a 3-4-mm surgical margin.

- In a study of 69 eyelid BCCs with five year follow-up after excision using 4-mm clinical margin there were no recurrences for noninfiltrative (nodular and superficial) BCCs and 4% recurrence rate for infiltrative tumors (Hamada 2005).

- Subclinical extension in 51 morpheaform BCCs averaged 7.2 mm (Wolf 1987).

- That study suggests need for 9-10 mm clinical margin for morpheaform (infiltrative) tumors.

- Tumor diameter greater than 2 cm, long standing duration and recurrence, aggressive histologic pattern, perineural and perivascular invasion — risk factors for significant subclinical extension, requiring large surgical margin (Walling 2004).

- In a retrospective analysis of 382 eyelid BCCs with follow-up of 5.7 years, recurrence rates increased from 5.36% after primary excision to 14.7% after secondary excision.

- Loaf of bread method — pathologist identifies longitudinal spread of the tumor, and studies two distal margins, assuming that width of surgical excision is adequate.

- Specimen is cut once, longitudinally down center of the lesion, cut edge is embedded and studied.

- Loaf of bread cross method — pathologist identifies longitudinal and horizontal spread of the tumor, and studies both distal margins and both wide margins, assuming that remainder of surgical excision is adequate.

- Specimen is cut twice, longitudinally down center, and horizontally across the width, all four edges are embedded and studied, each of four margins are determined separately.

- Lid margin excision differs from typical elliptical skin excision (superficial margin ends at the lid margin, deep margin ends at mucosal surface — two margins extend to “air”).

- Therefore, if loaf of bread cross method is used, only three margins are examined.

- If loaf of bread method is used, two vertical lid margin incisions are examined. (The pentagon of the lid margin excision is the “horizontal” extent, assumed to be tumor free).

- En-face frozen section histopathology is an alternative technique for studying lid margin tumors (Wong 2002).

- The primary tumor is excised as a wedge and submitted for permanent histopathology.

- Additional 1 mm taken from the medial and lateral edges, and third 1-mm margin from the periphery of the pentagon, are studied by frozen histopathology.

- Outer margins are embedded facing up.

- When residual tumor is noted, additional 1-mm margins are studied until all margins are clear.

- Particularly valuable technique when orientation of the tissue margin by the pathologist is less reliable — the surgical excision can be proven adequate if either edge of the specimen is negative for tumor.

- Even if the specimen is not oriented properly, only 1 mm of additional tissue will be sacrificed in confirming complete tumor removal.

- In a study of 77 lesions studied with this technique, and follow-up of up to 5 years, there were no cases of recurrence.

- For periocular BCC tumors that do not involve the lid margin studying entire periphery of surgical margin is preferred

- Many ophthalmic surgeons prefer to refer medial canthal BCCs for Mohs micrographic surgery.

- For lid margin tumors, the hemicircle extending above or below the lid margin tumor, representing 50% of the peripheral surgical margin, does not exist.

- Referral for Mohs’ micrographic surgery for a lid margin BCC, therefore, depends on the adequacy of available pathologic examination of vertical incisions at the lid margin.

- If pathologic evaluation is adequate at two vertical incisions, and peripheral surgical margins are wide, the Mohs’ technique does not offer distinct advantage over standard pathologic evaluation for lid margin tumors.

- Studies of frozen section histopathology for lid margin BCC have suggested that 95-100% tumor excision can be expected even with small surgical safety margins (Auw-Haedrich 2009).

- Presumes careful histopathologic examination of lid margin incisions, adequate clinical margins by surgeon, and wide peripheral excision by surgeon (Chalfin 1979).

- Doxanas et al. reported no recurrences among 39 tumors excised with frozen section control (Doxanas 1981).

- In that study, recurrence rate was 5% among 126 tumors when tumor margins were not monitored.

- Potential tissue preservation by Mohs technique refers to peripheral surgical margin for lid margin tumors

- Pathologic examination of lid margin is same for both techniques.

- Stereoscopic microdissection enhances frozen section control and improves cure rate (Levin 2009).

- Stereoscopic microscopic examination of the excised tissue, before cutting and embedding, facilitates accurate orientation of the surgical margin.

- Laser surgery, such as use of carbon dioxide laser, might be preferable when patient requires anticoagulants (Bandieramonte 1997).

- Area of tissue destruction is surrounded by 30-50 micron mantle of thermal coagulation with CO2 laser (Arndt 1982).

- BCC with deep tumor invasion might require exenteration for adequate resection.

- Among 64 patients with BCC and orbital invasion, presenting evidence of orbital invasion included mass with bone fixation, limitation of ocular motility and globe displacement (Leibovitch 2005).

- 64% were medial canthal tumors.

- 83% of BCC with orbital invasion were infiltrating and morpheaform types; 8% were basosquamous.

- In that study, 70% required exenteration.

- In an earlier study of 11 patients with orbital invasion by BCC exenteration was recommended in all cases (Howard 1992).

- In a recent study of 28 periocular BCCs that required exenteration, 53% were medial canthal lesions (Iuliano 2012).

- Radiotherapy can be combined with primary tumor debulking or secondary tumor excision.

- Deep recurrence and intracranial extension are risk with radiotherapy.

- BCC with anterior orbital invasion, including medial canthal lesions, is more recently managed with globe sparing tumor excision.

- In a study of 20 patients with medial canthal BCC and anterior orbital invasion, orbital extension was evident on radiologic imaging in 50% (Madge 2010).

- 12 of 20 had extraocular muscle movement restriction after deep orbital tumor excision.

- One tumor recurrence required exenteration, with mean 38 month follow-up.

Other management considerations

- Cryotherapy is a tissue sparing alternative to surgery

- Liquid nitrogen, nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide can be used as freezing agents.

- Double freeze thaw to temperature -50°C

- Alternate temperatures are -25° and -30°C

- Adequacy of tumor removal cannot be determined

- Tissue fibrosis can cause lid malposition.

- Pigment alteration and lid notching can limit cosmetic outcome.

- For smaller tumors — size less than 1–1.5 cm

- In a study of 100 primary periocular BCCs, maximum diameter 8mm, treated with nitrous oxide cryotherapy, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed a 5-year recurrence rate of 8% (Moesen 2011).

- Improvements in instrumentation, technology and training might advance the efficacy of cryosurgery for eyelid BCC (Buschmann 2002).

- Trials of sunscreen efficacy have shown protection for SCC but not BCC (Green 1999).

- Sunscreen might prevent multiple BCC (Pandeya 2005).

- Sunscreen protection is impractical for periocular, particularly lid margin BCC.

- Chronic use of nonselective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and COX-2 inhibitors, such as diclofenac and meloxicam, might reduce the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma but does not reduce the risk of BCC (Johannesdottir 2012).

- NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes which might be involved in carcinogenesis.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

- Referral for regular dermatology screening exams

- Once BCC has been detected, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend complete skin examination every 6 to 12 months for life (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2014).

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Tissue preservation balanced with adequate tumor excision and prevention of recurrence

- Complications are function of primary tissue destruction by tumor and morbidity associated with reconstruction (see associated outlines on lid reconstruction).

Disease-related complications

- Risk factors for exenteration with periocular BCCs has been studied (Iuliano 2012).

- In a cohort of 506 periocular BCCs in Naples, Italy, from 1984 to2003, the exenteration rate was 5.5% (28 patients), including 8 tumors that required exenteration as primary treatment.

- Tumors requiring exenteration were disproportionately in the medial canthus compared to the lower lid for other patients.

- Initial treatment without margin control was a significant risk factor for exenteration.

- Tumor type showing infiltration, as opposed to nodularity, was a significant risk factor.

- The recurrence rate after exenteration was 28%.

- Two patients died of tumor related causes.

- In a study of 417 BCCs treated in Sydney, Australia from 1990-2004 the same three factors — medial canthal location, morpheaform growth pattern, and incomplete excision — were risk factors for tumor recurrence (Nemet 2006;).

Historical perspective

- In a 1969 review of 273 eyelid BCCs, collected over prior fifteen years, the correct clinical diagnosis was only made in 60% of cases (Payne 1969).

- The recurrence rate was 12%.

- Tumor death rate was 2% (duration of lesion was 4–15 years).

- Exenteration rate was 3%.

- Four of 8 patients who required exenteration developed subsequent recurrence.

- Of 147 eyelid tumors treated at the Memorial Hospital in New York City 1925–1935, 85% were BCCs, 54% were lower lid, and 28% medial canthus (Martin 1939).

- In 1824, Jacob, a Dublin oculist, described “an ulcer of peculiar character which attacks the eyelids and other parts of the face” (Dublin Hosp Rep 1824;4:232).

- The term ulcus rodens was first used by Hermann Lebert in 1851 (Jackson 1995).

- The lesion resembled something a rat had gnawed.

- In 1853 Sir James Paget introduced the term rodent ulcer (Paget 1953).

- Komprecher in 1903 suggested origin from basal epidermis and introduced the term basal cell carcinoma (Kromprecher 1903).

- Prior to the 1800s these lesions were called “noli me tangere,” which means do not touch, a Biblical reference to St. John, chapter 20, verse 17 — these lesions were considered incurable until the mid-19th century when surgical excision became popular (Bennett 1974).

References and additional resources

- Aldred WV, Ramirez VG, Nicholson DH. Intraocular invasion by basal cell carcinoma of the lid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98(10):1821-1822.

- Alfawaz AM, Al-Hussain HM. Ocular manifestations of xeroderma pigmentosum at a tertiary eye care center in Saudi Arabia. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27(6):401-404.

- Arndt KA, Noe JM. Lasers in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118(5):293-295.

- Auw-Haedrich C, Frick S, Boehringer D, Mittelviefhaus H. Histologic safety margin in basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:802.

- Bandieramonte G, Lepera P, Moglia D, et al. Laser microsurgery for superficial T1-T2 basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid margins. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(7):1179-1184.

- Bennett JP. From noli-me-tangere to rodent ulcer: the recognition of basal cell carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 1974;27(2):144-154

- Blasi MA, Giammaria D, Balestrazzi E. Immunotherapy with imiquimod 5% cream for eyelid nodular basal cell carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1136-1139.

- Buschmann W. A reappraisal of cryosurgery for eyelid basal cell carcinomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(4):453-457.

- Carneiro RC, de Macedo EM, Matayoshi S. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of periocular Basal cell carcinoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(2):100-102.

- Chalfin J, Putterman AM. Frozen section control in the surgery of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87(6):802-809.

- Cook BE Jr, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(4):746-750.

- Doxanas MT, Green WR, Iliff CE. Factors in the successful surgical management of basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;91(6):726-736.

- Garcia-Martin E, Gil-Arribas LM, I

- Hamada S, Kersey T, Thaller VT: Eyelid basal cell carcinoma: non-Mohs excision, repair and outcome. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89:992-994.

- Kahane A, Worden FP, Einer VM: Vismodegib for eye-threatening orbital basal cell carcinoma: A clinicopathologic report. JAMA Ophthalmic 2013; 131:1364-1366.

- Karagas MR, Waterboer T, Li Z, et al: Genus beta human papillomavirsuses and incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin: population based case-control study. Br Med J 2010; 341:c2986.

- Kiiski V, de Vries E, Flohil SC, Bijl MJ, et al: Risk factors for single and multiple basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146:848-855.

- Kirzhner M, Jakobiec F: Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features of pigmented basal cell carcinomas of the eyelids. Am J Ophthalmic 2012; 153:242-252.

- Leonardi-Bee J, Ellison T, Bath-Hextall F: Smoking and the risk on nonmelanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol 2012; 148:939-946.

- Puccioni M, Santoro N, Giansanti F, et al: Photodynamic therapy using methyl aminolevulinate acid in eyelid basal cell carcinoma: a 5-year follow-up study. Ophthal Pl Reconstr Surg 2009; 25:115-118.

- Rubin AI, Chen EH, Ratner D: Basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2262-2269.

- Walling HW, Fosko SW, Geraminejad PA, et al: Aggressive basal cell carcinoma: Presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Cancer Metast Rev 2004; 23:389-402.

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren M, et al: Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systemstic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J 2012; 345:e5909.

- Wojno TH: The association between cigarette smoking and basal cell carcinoma of the eyelids in women. Ophthalmic Pl Reconstr Surg 1999; 6:390-392.

- Wolf DJ, Zitelli JA: Surgical margins for basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 1987; 123:340-344.

- Wu S, Han J, Li W, Li T, Qureshi AA: Basal-cell carcinoma incidence and associated risk factors in U.S. women and men. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178:890-897.

- R Zanetti 1, S Rosso, C Martinez, A Nieto, A Miranda, M Mercier, D I Loria, A Østerlind, R Greinert, C Navarro, G Fabbrocini, C Barbera, H Sancho-Garnier, L Gafà, A Chiarugi, R Mossotti. Comparison of risk patterns in carcinoma and melanoma of the skin in men: a multi-centre case-case-control study. Br J Cancer 2006 Mar 13;94(5):743-51.