Benign Eyelid Neoplasia

Updated August 2024

Suzanne K. Freitag, MD; Nahyoung Grace Lee, MD; Edward J. Wladis, MD

Benign neoplasia are among the many lesions that commonly occur on the eyelids. Other articles in this series discuss malignant neoplasia, actinic keratosis, non-neoplastic degenerations, cysts, inflammations, and other diseases. Although benign, nevi and related lentiginous masses are also separately discussed. Features and management of individual lesions are discussed below. It is worth noting that clinical diagnoses are sometimes inaccurate and in one study, experienced physicians were mistaken in greater than 10% of cases (Norman 1989); hence a biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis is always a reasonable option, particularly in cases of clinical diagnostic uncertainty.

Syringoma

Establishing the diagnosis

- Etiology and epidemiology

- Benign eccrine sweat gland tumor

- Most cases are sporadic, but there is a genetic autosomal dominant inheritance pattern (Font 2006).

- More common in young women

- Slight predilection in Asians (Font 2006)

- Clinical features

- Can be subtle and not noticeable to the patient

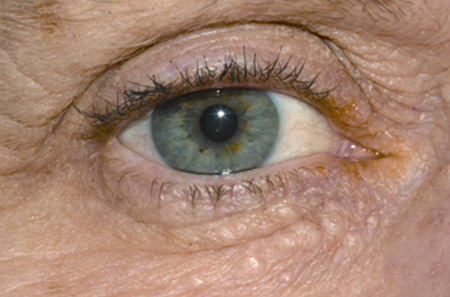

- Characteristic appearance: yellow-brown in color, flat or rounded, and cystic (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Syringoma.

- Can be solitary or multiple

- Multiple variants are often bilateral, symmetric, and most prominent on the lower eyelids.

- Range in size from 1–3 mm

- Evaluation to establish the diagnosis

- Definitive diagnosis by histopathology

- Numerous small ducts embedded in sclerotic stroma in the superficial dermis (Font 2006)

- Walls of ducts are lined by 2 rows of cuboidal-to-flattened epithelial cells (Saitoh 1993).

- Lumen contain periodic acid-Schiff-positive, eosinophilic, amorphous debris.

- Ducts may show a “tadpole” or comma-shaped extension of small basaloid cells.

Risk factors

- Down syndrome

- Chromosomal aberrations in Down syndrome predispose people to dysfunction of sweat glands (Saitoh 1993).

- Up to 18% of people with Down syndrome develop sweat-gland tumors.

- Diabetes mellitus: Pathogenesis unknown

- Marfan syndrome

- Connective tissues and exocrine glands are affected, leading to overproduction of sweat glands (Font 2006).

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

- Overproduction of sweat leading to sweat-gland tumors (Font 2006)

Differential diagnosis

- Acne Vulgaris

- Apocrine hidrocystoma

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Milia

- Pilomatrixoma

- Sebaceous adenoma

- Sebaceous hyperplasia

- Trichoepithelioma

Clinical management

- Observation

- Surgical excision, with particular attention to removing the deep core of the lesion

- CO2 laser ablation (Cho 2011), especially useful when multiple

Complications of treatment

- Rare; recurrence uncommon, unless multiple

- Post-laser transient hyperpigmentation (Hasson 2012)

Trichilemmoma

Establishing the diagnosis

- Etiology and epidemiology

- Originate from the outer sheath of the hair follicle

- Sporadic cases are common (Font 2006).

- Most commonly occurs in white females

- Multiple tumors may be a marker of Cowden’s disease or multiple hamartoma syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition with an increased risk of breast, thyroid, and gastrointestinal carcinoma.

- Clinical features

- Slow growing, asymptomatic papule and/or plaque on the face

- Can be solitary or multiple (Hidayat 1980)

- Rarely involves the lid margin or the inner canthus

- Flesh-colored, nodular or papillomatous, resembling verruca vulgaris or basal cell carcinoma (Hidayat 1980)

- Vary in size from 1 to 5 mm in diameter on the face or neck (Font 2006)

- Testing and evaluation to establish the diagnosis

- Definitive diagnosis by histopathology

- Glycogen-rich cells with clear cytoplasm (Font 2006)

- Peripheral palisading of columnar cells

- Often gets misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma

Risk factors

- Association with Cowden syndrome: Autosomal dominant with abnormal PTEN tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 10q23 (Al-Zaid 2012).

- Postulated that these could be caused by a virus because of morphologic and histologic features that they share with verruca

Differential diagnosis

- Verrucca vulgaris

- Acneiform eruptions

- Cutaneous horn

- Folliculoma

- Trichoepithelioma

- Trichofolliculoma

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Trichilemmal carcinoma

Clinical management

- Observation

- Surgical excision

- Laser ablation (CO2)

- Cryosurgery (Shields 2008)

Complications of treatment

Rare; recurrence uncommon, unless multiple

Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe)

Establishing the diagnosis

- Etiology and epidemiology

- Develops from hair matrix cells

- Unknown etiology; sporadic and familial

- Familial cases have been observed but mode of inheritance is unclear (Zloto 2014)

- Tendency to affect young individuals

- Involves the periorbital region in 17% of cases (Font 2006)

- 40% develop in the first decade of life, 20% in the second (Font 2006).

- Pertinent elements of the patient history

- Slow growing, over months to years

- Asymptomatic, but can encounter episodes of inflammation or ulceration

- Rapid growth is rare, but there have been reports.

- Clinical features

- Subcutaneous red to blue mass that is fairly well circumscribed, freely movable, and firm or gritty to palpation (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Pilomatrixoma (Kumar 2008)

- Some reaching 1 cm in 2 weeks (Zloto 2014)

- Characteristic location near the lateral aspect of the eyebrow

- Most commonly involve the head and neck region followed by upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities.

- Average size of 10 mm or less (Shields 2008)

- Can be cystic to firm with intact overlying skin with telangiectatic vessels

- Testing and evaluation to establish the diagnosis

- Definitive diagnosis by histopathology

- Histopathology shows large masses of shadow cells, combined with basophilic cells, inflammation, foreign body giant cells, calcification, and ossification.

- Ultrasonography shows calcification within an ovoid complex mass at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous fat (Zloto 2014).

- Fine-needle aspiration leads to misinterpretation of the lesion as carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and pleomorphic adenoma (Font 2006).

- Calcium deposits are seen in 75% of lesions (Levy 2008).

Risk factors

- Multiple pilomatrixoma cases have been seen to have mutation in CTNNB1 gene (Levy 2008).

- Associated disorders with multiple pilomatrixoma include myotonic dystrophy, Gardner syndrome, hypercalcemia, and sarcoidosis (Levy 2008).

- Some consider pilomatrixoma a cutaneous marker of myotonic dystrophy.

Differential diagnosis

- Epidermoid cyst

- Dermoid cyst

- Sebaceous adenoma

- Juvenile xanthogranuloma

- Chalazion

- Keratoacanthoma

- Kaposi sarcoma

- Pilomatrix carcinoma

Clinical management

- Surgical excision with clean margins using shallow dissection and relaxed skin tension lines where possible

Complications of treatment

Recurrence with incomplete resections

Oncocytoma

Establishing the diagnosis

- Etiology and epidemiology

- Stems from glandular epithelium and occurs in various organs such as the salivary, thyroid, parathyroid, pituitary, and adrenal glands (Font 2006)

- Oncocytic metaplasia of ductal and acinar cells of lacrimal epithelium or conjunctival epithelium

- No clear inheritance pattern

- Often occurs in older individuals (>60 years)

- Male to female ratio is 1:5 (Shields 2008).

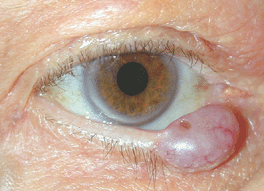

- Cutaneous oncocytoma is extremely rare with fewer than 5 case reports (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Oncocytoma (Cameron 2005).

- Most periocular oncocytomas are seen at the caruncle (Wobser 2013) but may also occur at the mucocutaneous border of the eyelid, the lacrimal sac, or the conjunctiva.

- Pertinent elements of the patient history

- Slow growing and asymptomatic

- Rarely presents with unilateral conjunctivitis and epiphora

- Clinical features

- Solitary and unilateral

- Mean size and 4 x 4 x 3 (Shields 2008)

- Can be solid or cystic

- Red/tan color

- Testing and evaluation to establish diagnosis

- Diagnosis established by histopathology

- Benign oncocytes seen on pathology as uniform, oval cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Font 2006)

- Nuclei are small, round with a single nucleolus

- Occasional goblet cells are scattered within the epithelial lining

- Composed of tubules lined by tall columnar epithelium with finely granular cytoplasm (Font 2006)

Risk factors

- None

Differential diagnosis

- Caruncular nevus

- Papilloma

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Sebaceous adenoma

- Sebaceous hyperplasia

Clinical management

- Observation

- Local excision

Complications of treatment

- Scarring

- Eyelid deformity

Eyelid neurofibroma

Establishing the diagnosis

- Epidemiology

- Results from proliferation of all elements of a peripheral nerve

- Increased incidence with age, most common over 40–50 (Font 2006)

- Rare familial forms exist

- Pertinent elements of the patient history

- Gradual onset

- Chronic course

- Clinical features

- Neural tumor that can affect skin in all parts of the body

- Solitary lesions are unassociated with systemic disease

- Multifocal or diffuse lesions are associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis (Shields 2008)

- Eyelid and orbit can be involved by

- Solitary neurofibroma (fibroma molluscum)

- Multiple localized neurofibromas

- Plexiform neurofibroma (Shields 2008)

- Plexiform neurofibromas develop in young children as a thickening of the entire eyelid that causes an S-shaped curve to the margin of the upper eyelid (Figure 4)

Figure 4. Eyelid neurofibroma.

- Plexiform neurofibromas can extend into the eyebrow, conjunctiva, and orbit

- Testing and evaluation to establish diagnosis

- Diagnosis established by histopathology

- Composed of combination of Schwann cells, peripheral nerve axons, neural fibroblasts, and perineural cells (Bechtold 2012)

Risk factors

Type 1 neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen’s disease)

Differential diagnosis

- Chalazion

- Subcutaneous or orbital capillary hemangioma

Clinical management

- Observation of small, asymptomatic solitary neurofibromas

- Surgical excision or debulking

- Use of CO2 laser at time of surgical resection for hemostasis (Bechtold 2012)

Infantile capillary hemangioma

Establishing the diagnosis

- Etiology

- Hamartomatous neoplasm of endothelial cells (Font 2016)

- Exact pathogenesis is unknown

- Speculation of genetic component

- Epidemiology

- Most common benign periorbital tumor of childhood

- 4–5% incidence

- Racial predilection for Caucasians (10–12%) compared to blacks (1.4%) and Taiwanese and Japanese (0.2–1.7%) (Callahan 2012)

- Pertinent elements of the patient history

- Periocular hemangiomas can be noted at birth (Shields 2008)

- Usually become manifest within the first 2-6 weeks of life; nearly all are identified by six months of age

- Clinical features

- Superficial lesions appear as bright red papules or nodules and will blanch with pressure, which distinguishes them from port-wine stains (Figure 5) (Font 2006; Callahan 2012)

Figure 5. Infantile Capillary Hemangioma.

- Deeper lesions result in an array of cutaneous color tone changes, and may present with a blue or purple coloration (Callahan 2012).

- Usually follows a typical course divided into the following stages (Callahan 2012):

- Nascent (0–3 months)

- Early proliferative (6–10 months)

- Late proliferative (6–10 months)

- Plateau (variable)

- Involution (half by 4 years of age and 3 quarters by 7 years)

- Abortive

- Amblyopia is the most common ophthalmic complication of infantile hemangioma and affects 40–60% of patients.

- Systemic complications are associated with multifocal hemangiomas (more than 5 cutaneous lesions): PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial abnormalities, cardiac defects/aortic coarctation, and eye abnormalities, Shields 2008)

- Kasabach-Merritt syndrome: thrombocytopenia with bleeding diathesis due to platelet entrapment with a large capillary hemangioma

- For superficial lesions, diagnosis is usually clinical.

- Lesions with deeper components can be evaluated with ultrasonography, which shows an increased vessel density and high-flow pattern (Rizvi 2013).

- The extent of deeper lesions can best be evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging, which demonstrates lesions that are isointense to extraocular muscles on T1 imaging and hyperintense on T2.

- Computed tomography is generally not recommended for children in this vulnerable age group.

- For lesions of unclear etiology or unusual appearance, biopsy can be performed.

- Histopathology

- Diagnosis is confirmed with GLUT-1 on immunohistochemistry, which is expressed only in infantile hemangioma endothelium (Font 2006).

Risk factors

- Prematurity, low birth weight, multiple gestations, and advanced maternal age

- Chorionic villus sampling has been stipulated as a risk factor, but the literature lacks robust confirmatory data (Callahan 2012).

Differential diagnosis

- Port-wine stain (nevus flammeus)

- Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

- Tufted angioma (Rizvi 2013)

Clinical management

(Callahan 2012)

- Observation because lesions can involute spontaneously

- Systemic beta blockers: Studies show 100% arrest of progression of hemangiomas and regression of deep orbital hemangiomas.

- Treatment is typically coordinated with pediatrician who will follow for systemic side effects.

- Topical beta-blockers: Superficial hemangiomas are successfully treated with 0.1% or 0.5% timolol maleate twice daily. Studies report a reduction in size ranging from 55–95%.

- Intralesional beta blockers: Injection of propranolol 1 mg/mL demonstrated 40% excellent response, 40–45% fair or good response, and 20% no response.

- Systemic steroids: Large doses of prednisone demonstrated an 84% response rate after 2 months of therapy.

- Intralesional steroids: Mixture of betamethasone and triamcinolone is injected into the lesion with a volume of 1–2 mL depending on the size of the lesion. Response can be drastic and rapid.

- Topical steroids: 1/3 had a good response, 1/3 a partial response, and 1/3 failed to respond.

- Interferon-alpha: Systemic anterferon-alpha induced regression of half or more in 90% of cases.

- Laser (pulse dye laser): destruction of the hemangioma using light of the same wavelength as vessels; effective in treatment of superficial lesions. Laser arrested progression of 97% of hemangiomas, completely resolved 14%, and partially regressed 15%.

- Surgical excision

Complications and side effects of treatment

(Callahan 2012)

- Systemic steroids: behavioral changes, irritability, cushingoid appearance, and growth delay

- Intralesional steroids: ophthalmic artery embolization, cutaneous hypopigmentation, fat atrophy, calcification, and full thickness eyelid necrosis

- Topical steroids: skin hypopigmentation, hypertrichosis, glaucoma, cataract formation

- Interferon-alpha: neutropenia and spastic diplegia with 10–30% risk of neurotoxicity; treatment was abandoned.

- Vincristine: peripheral neuropathy, constipation, jaw pain, and hematologic toxicity

- Pulsed dye laser: hyperpigmentation and atrophic scarring

- Surgery: intraoperative hemorrhage

- Systemic beta blockers: hypotension, bradycardia, bronchospasm, congestive heart failure, hypothermia, sleep disturbance, blunted hypoglycemic response

- Topical beta blockers: sleep disturbance in 1 patient

- Intralesional beta blockers: no side effects

Disease-related complications

Amblyopia

Lymphangioma/lymphatic malformation

Establishing the diagnosis

- Etiology and epidemiology

- Hamartomatous growth of lymph channels (Font 2006)

- Eyelid lesions are typically more diffuse, but easier to manage than orbital lesions (Shields 2008).

- Can be associated with concomitant conjunctival and facial lesions

- Majority of eyelid lymphangiomas represent anterior extension of orbital lesions or extension of facial lesions (Pang 1984).

- Caused by blockage of the lymphatic system as fetus develops (Goble 1990)

- More than 50% are evident at birth and 90% become apparent by the 2 year of life (Goble 1990).

- Clinical features

- Deep to epidermis as dark blue, soft, fluctuant mass (Font 2006)

- Slow growing

- Might not be clinically apparent until there is bleeding into a pre-existing subclinical lymphangioma

- Spontaneous or post-traumatic bleeding into the lymph channels can produce blood-filled cavitary pseudocysts (“chocolate cysts”).

- True regression does not occur with lymphangioma (Shields 2008).

- Can clinically resemble a varix or varices

- Testing and evaluation to establish diagnosis

- Ultrasound biomicroscopy can reveal subcutaneous mass with multicystic internal structure and fluid levels (Horgan 2008).

- Definitive diagnosis by histopathology; 3 types of lymphangiomas:

- Dermal (lymphangioma circumscriptum)

- Cavernous: most common in the ocular adnexa and orbit

- Cystic: frequently involves the neck (cystic hygroma)

- Subepidermal lymphatic vesicles of lymphangioma circumscriptum are endothelium-lined spaces that are completely separate from the normal lymphatic system (Goble 1990).

Risk factors

- Maternal alcohol use (Horgan 2008)

- Viral infections during pregnancy

- Cystic lymphangioma is associated with Noonan syndrome, Down syndrome, and Turner syndrome.

Differential diagnosis

- Hemangioma

- Varix

- Glomus tumor

- Malignant melanoma

- Epidermal cyst

- Venous angiomas

- Herpetic vesicles

Clinical management

- Observation

- Surgical resection for circumscribed tumors

- Surgical debulking for diffuse, symptomatic tumors (Shields 2008), with or without the use of fibrin glue (Boulos 2005)

- Percutaneous drainage and ablation with sclerosing agents. (Hill, 2012)

- There are reports of success with systemic treatment with sildenafil. (Gandhi, 2013)

- Sirolimus may be an effective treatment for lymphangioma of the head and neck. A review article analyzed 28 studies, with 105 children and found nearly 91% responded to sirolimus treatment. Side effects of this treatment included neutropenia and infections. (Wiegand S, Dietz A, Wichmann G. Efficacy of sirolimus in children with lymphatic malformations of the head and neck.)

- A systematic review of orbital lymphangiomas analyzed 9 case series and 10 patients, and found partial or complete response in all of the patients (Shoji et al. The Use of Sirolimus for Treatment of Orbital Lymphatic Malformations: A Systematic Review. OPRS 2020).

Complications of treatment

Recurrence with incomplete resections

Sebaceous adenoma

Establishing the diagnosis

- Occurs on skin of the eyelids, meibomian glands, and sebaceous glands of the caruncle in older individuals (Singh 2005)

- Clinical features

- Tan, pink, or yellow nodules or papules usually 5 mm in greatest dimension (Font 2006)

- Can be clinically mistaken for basal cell carcinoma (Singh 2005)

- Can display overlying crusting or ulceration

- Lobular and organoid architecture (Takayama 2013)

- Slow growth

- Sebaceous adenoma associated with Muir-Torre syndrome can undergo cystic change, whereas those of sporadic type do not exhibit this feature (Singh 2005).

- Testing and evaluation to establish the diagnosis

- Definitive diagnosis by histopathology

- Connection or replacement of the overlying squamous epithelium (Font 2006)

- Expansion and increased prominence of the peripherally located basaloid cells (Shields 2008)

- Compared to sebaceous hyperplasia, there is an increase in the number of germinative cells (Singh 2005).

- Maintains a prominent population of mature sebocytes often concentrated in the central portion of the neoplasm

- Bubbly or multivacuolated cytoplasm and crenated nuclei are helpful features to differentiate them from other eccrine, melanocytic, keratinocytic, or xanthomatous lesions (Font 2006).

Risk factors

- Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS)

- Autosomal dominant disorder characterized by sebaceous gland adenoma or carcinoma, keratoacanthomas, gastrointestinal malignancies, and other systemic tumors (Shalin 2010)

- Number of sebaceous adenomas can range from 1 to >100.

- 43% of patients with MTS were diagnosed with colorectal malignancies followed by genitourinary (21%) and breast (14%) (Rishi 2004)

- Family history of visceral malignancies is prominent in patients with malignancy and MTS (Singh 2005)

- Viral infections during pregnancy (Shalin 2010)

- Cystic lymphangioma is associated with Noonan syndrome, Down syndrome, and Turner syndrome (Singh 2005)

Differential diagnosis

- Sebaceous hyperplasia

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Seborrheic keratosis

- Sebaceous carcinoma

Clinical management

- Complete surgical resection

- Medical workup for Muir-Torre syndrome with referral to gastroenterologist

Complications of treatment

Recurrence with incomplete resections

References and additional resources

- Al-Zaid T, Ditelberg JS, Prieto VG. Trichilemmomas show loss of PTEN in Cowden syndrome but only rarely in sporadic tumors. J Cut Pathol. 2012;39;493-499.

- Alniemi ST, Griepentrog GJ, Diehl N et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of periocular infantile hemangiomas. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(7):889-893.

- Bechtold D, Hove HD, Prause JU, et al. Plexiform neurofibroma of the eye region occurring in patients without neurofibromatosis type 1. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(6):413-415.

- Boulos PR, Harissi-Dagher M, Kavalec C, Hardy I, Codère F. Intralesional injection of Tisseel fibrin glue for resection of lymphangiomas and other thin-walled orbital cysts. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2005 May;21(3):171-6.

- Callahan AB, Yoon MK. Infantile hemangiomas: A review. Saud J Ophthalmol. 2012;26(3):283-291.

- Cameron JR, Barras CW. Oncocytoma of the eyelid. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2005;83(1):125.

- Cho SB, Kim HJ, Noh S et al. Treatment of syringoma using an ablative 10,600-nm carbon dioxide fractional laser: a prospective analysis of 35 patients. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(4):433-438.

- Gandhi NG, Lin LK, O’Hara M. Sildenafil for pediatric orbital lymphangioma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:1228-30.

- Font RL, Croxatto JO, Rao NA. Tumors of the eye and ocular adnexa (AFIP atlas of tumor pathology). Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology in collaboration with the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2006.

- Goble RR, Frangoulis MA. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the eyelids and conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:574-575.

- Hasson A, Farias MM, Nicklas C, Navarrete C. Periorbital syringoma treated with radiofrequency and carbon dioxide (CO2) laser in 5 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(7):879-880.

- Hidayat AA, Font RL. Trichilemmoma of eyelid and eyebrow. A clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98(5):844-847.

- Hill RH 3rd, Whiels WE 2nd, Foster JA, et al. Percutaneous drainage and ablation as first line therapy for macrocystic and microcystic orbital lymphatic malformations. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:119-25.

- Horgan N, Shields CL, Minzter R, et al. Ultrasound biomicroscopy of eyelid lymphangioma in a child. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2008;45:55-56.

- Kumar S. Rapidly growing pilomatrixoma on eyebrow. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2008;56:83-84.

- Levy J, Ilsar M, Deckel Y et al. Eyelid pilomatrixoma: a description of 16 cases and a review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(5):526-535.

- Norman GR, Rosenthal D, Brooks LR et al. The development of expertise in dermatology. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125(8):1063-1068.

- Pang P, Jakobiec FA, Iwamoto T et al. Small lymphangiomas of the eyelids. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1278-1284.

- Rishi, K and Font R. Sebaceous Gland Tumors of the Eyelids and Conjunctiva in the Muir-Torre Syndrome: A Clinicopathologic Study of Five Cases and Literature Review. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:31-36.

- Rizvi SA, Yusuf F, Sharma R, Rizvi SW. Management of superficial infantile capillary hemangiomas with topical timolol maleate solution. Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30(1):62-64.

- Saitoh A, Ohtake N, Fukuda S. Clear cells of eccrine glands in a patient with clear cell syringoma associated with diabetes mellitus. Am J Dermatopathol 1993;15:166-168.

- Shalin SC, Lyle S, Calonje E, et al. Sebaceous neoplasia and the Muir-Torre syndrome: important connections with clinical implications. Histopathology. 2010;56:133-147.

- Shields JA, Shields CL. Eyelid, Conjunctival, and Orbital Tumors. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. 2008.

- Singh AD, Mudhar HS, Bhola R, et al. Sebaceous Adenoma of the Eyelid in Muir-Torre Syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:562-565.

- Takayama K, Usui Y, Ito M, et al. A case of sebaceous adenoma of the eyelid showing excessively rapid growth. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:667-670.

- Wobser M, Haferkamp S, Roth S, et al. Periocular cutaneous oncocytoma with signs of disrupted oxygen metabolism. J Cutan Pathol. 2013 Dec;40(12):1054-1058.

- Zloto O, Fabian ID, Dai VV. Periocular pilomatrixoma: a retrospective analysis of 16 cases. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(1):19-22.