Uncommon Orbital Lesions: Solitary Fibrous Tumors

Updated June 2025

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Rare spindle cell tumor that arises from mesenchymal cells

- Typically found in the pleura, pericardium, peritoneum, liver, and kidneys, and only rarely in the head and neck; between 1994 and 2018, only 90 cases of orbital solitary fibrous tumor reported (Shen, Cancer Manag Res 2018)

- Can have endothelial differentiation and significant vascularity

- Typically behaves in a benign manner, but malignancy, recurrence, invasion, and metastasis can occur (Bernardini, Ophthalmology 2003)

Epidemiology

(Le, Orbit. 2014)

- Most common in adults 30–50 years old

- Can occur at any age; children as young as 5 have been reported (Blandamura, J Clin Pathol 2014)

- 90 cases of orbital solitary fibrous tumors (SFT) reported in the literature

- Slight male predilection

History

- Slowly progressive, painless proptosis (most common sign)

- Decreased vision

- Diplopia

- Previous history of orbital tumor

Clinical features

Figure 1. Frontal photo demonstrating right inferolateral globe dystopia, exophthalmos, and exotropia from solitary fibrous tumor.

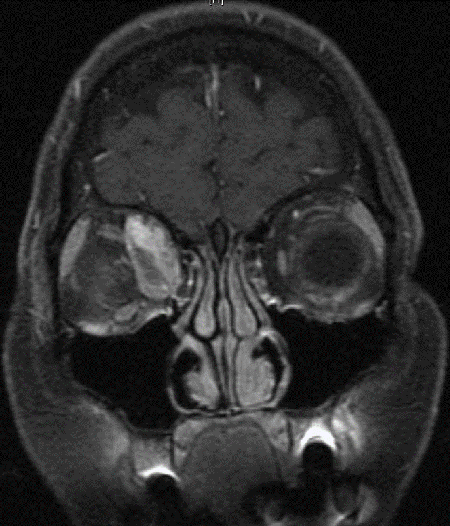

Figure 2. Coronal MRI of patient in Figure 1.

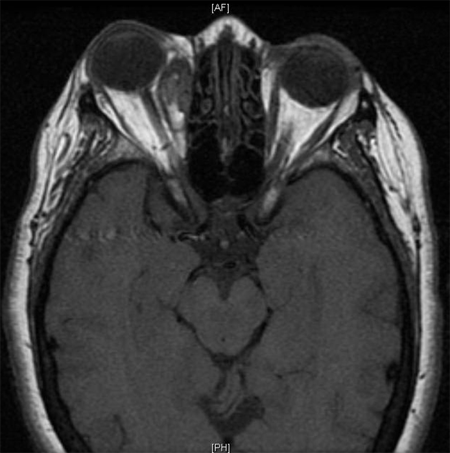

Figure 3. Axial MRI of same patient. Image courtesy Anne Barmettler, MD.

Figure 4. Frontal photo of patient with right orbital solitary fibrous tumor causing ptosis, edema, and erythema.

- Proptosis

- Dystopia

- Lid swelling

- Decreased motility

- Ptosis

- Chemosis

- Loss of vision due to optic neuropathy are rare.

- Typically occurs superiorly, but can occur anywhere in the orbit

- 20% superomedial

- 15% medial

- 13% superotemporal

- 7% inferotemporal

Testing

- Evaluation of motility, vision, pupils, Hertel exophthalmometry

- CT scan (Dalley, Radiol Clin North Am 1999; Kim, AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008)

- Typically well circumscribed, but can be irregular

- Nonencapsulated

- Bone erosion is rare, but can occur with longstanding, recurrent, or aggressive lesions

- 25% have focal areas of calcification

- Significant feeder vessels and enhancement is seen with intravenous contrast

Figure 5. Axial CT of patient from Figure 4 showing lateral orbital mass. Image courtesy Greg Griepentrog, MD.

- MRI (Dalley, Radiol Clin North Am 1999; Kim, AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008)

- T1

- Heterogenous

- Isointense to muscle, hypointense to fat

- T2

- Hypointense to muscle, hyperintense to fat

- Areas of signal void due to large blood vessels

- More heterogeneity

- Homogenous enhancement with gadolinium

- Flow voids indicating hypervascularity may be a common finding

- Echography (Johnson, Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2003)

- Firm, low-to-medium internal reflectivity, regular internal structure, moderate sound attenuation, vascularity

- Histopathology

- Well circumscribed

- Dense spindle cells with scant cytoplasm

- “Patternless pattern” consisting of thick bands of collagen with areas of hyper- and hypocellularity, storiform and fascicular formations, and neural-type palisades (Heathcote, Can J Ophthalmol 1997)

- Bands of collagen are a distinguishing feature not found in fibrous histiocytoma or hemgiopericytoma (Tam, Orbit 2008).

- Vascular channels

- Recurrent lesions can have mitotic figures, nuclear pleomorphism, and necrosis.

- Immunohistochemical staining

- Vimentin

- CD34 strongly positive in 90%–100% (Westra, Am J Surg Pathol 1994)

- Hemangiopericytomas by contrast tend to be weakly positive.

- Other tumors on the differential do not exhibit CD34 activity.

- Useful in differentiating from fibrous histiocytoma and hemangiopericytoma

- Malignant SFTs have been reported to lack reactivity (Girnita, Acta Ophthalmol. 2009)

- Malignant behavior is suggested by hypercellularity, tumors larger than 5 cm, more than four mitotic figures per 10 high-power microscopic fields, and tissue necrosis (Shen 2018).

Risk factors

- Middle-aged adults

Differential diagnosis

- Cavernous hemaniogoma

- Hemangiopericytoma

- Fibrous histiocytoma

- Schwannoma

- Glioma

- Meningioma

- Giant cell angiofibroma

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Typically a benign lesion with a rare possibility of recurrence and malignant transformation

Medical therapy

Radiatiotherapy has been used in cases of malignant transformation following subtotal excision (Blandamura, J Clin Pathol 2014).

Surgery

Complete excision is the mainstay of treatment.

Surgery can be complicated by significant bleeding due to vascularity of the lesion.

Friable lesions and infiltrative borders can lead to subtotal excision.

- Blandamura et al. reported 4 cases of subtotal excision where 3 of 4 patients did well postoperatively; however, 1 had a malignant transformation.

- Close follow-up could be considered in cases of residual disease with nonaggressive features on histopathology.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Surgical complication: risk of intraoperative bleeding due to lesion vascularity

Disease-related complications

(Verity, OPRS 2023)

- Recurrence:

- Surgically intact removal – 3% recurrence rate

- Surgically macroscopic dissection with cell spillage – 30% recurrence rate

- Incomplete excision – 82% recurrence rate

- Malignant transformation can occur in recurrent cases

- Future metastasis 3%

- 10 year progression-free survival

- Surgically intact removal – 94%

- Surgically macroscopic dissection with cell spillage – 60%

- Incomplete excision – 36%

Patient instructions

Patients need to be aware of the possibility of recurrence, malignancy and metastasis.

In addition to being followed closely, they need to note worsening vision, diplopia, or proptosis.

References and additional resources

- AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. 2010-11.

- Bernardini FP, de Conciliis C, Schneider S, Kersten RC, Kulwin DR. Solitary fibrous tumor of the orbit: Is it rare? Report of a case series and review of the literature. Ophthalmology. 2003; 110:1442–1448.

- Black EH, et al. Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2012; 860-1.

- Blandamura S, Alaggio R, Bettini G, Guzzardo V, Valentini E, Bedogni A. Four cases of solitary fibrous tumour of the eye and orbit: one with sarcomatous transformation after radiotherapy and one in a 5-year-old child’s eyelid. J Clin Pathol. 2014 Mar;67(3):263-7.

- Dalley RW.Fibrous histiocytoma and fibrous tissue tumors of the orbit. Radiol Clin North Am. 1999 Jan;37(1):185-94.

- Girnita L, Sahlin S, Orrego A, Seregard S. Malignant solitary fibrous tumour of the orbit. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009 Jun;87(4):464-7.

- Heathcote JG. Pathology update: solitary fibrous tumour of the orbit. Can J Ophthalmol. 1997 Dec;32(7):432-5.

- Johnson TE, Onofrey CB, Ehlies FJ. Echography as a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of orbital solitary fibrous tumor. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Jan;19(1):68-74.

- Kim HJ, Kim HJ, Kim YD, Yim YJ, Kim ST, Jeon P, Kim KH, Byun HS, Song HJ. Solitary fibrous tumor of the orbit: CT and MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008 May;29(5):857-62.

- Le CP, Jones S, Valenzuela AA. Orbital solitary fibrous tumor: a case series with review of the literature. Orbit. 2014 Apr;33(2):145-51.

- Roelofs KA, Juniat V, O’Rouke M, et al. Radiologic Features of Well-circumscribed Orbital Tumors With Histopathologic Correlation: A Multi-center Study. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2024 Jul-Aug 01;40(4):380-387.

- Rootman J. Diseases of the Orbit: A multidisciplinary approach. 2nd revised edition, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002; 273-4.

- Shen J, Li H, Feng S, Cui H. Orbital solitary fibrous tumor: a clinicopathologic study from a Chinese tertiary hospital with literature review. Cancer Manag Res; 2018 10: 1069-1078.

- Tam ES, Chen EC, Nijhawan N, Harvey JT, Howarth D, Oestreicher JH. Solitary fibrous tumor of the orbit: a case series. Orbit. 2008;27(6):426-31.

- Vahdani K, Rose GE, Verity DH. Long-Term Surgical Outcome for Orbital Solitary Fibrous Tumors. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023 Nov-Dec 01;39(6):606-613.

- Westra WH, Gerald WL, Rosai J. Solitary fibrous tumor. Consistent CD34 immunoreactivity and occurrence in the orbit. Am J Surg Pathol.1994; 18:992–998.

- Young TK, Hardy TG. Solitary fibrous tumor of the orbit with intracranial involvement. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 May-Jun;27(3).

- Ziegenfuß C, van Landeghem N, Meier C, et al. MR Imaging Characteristics of Solitary Fibrous Tumors of the Orbit : Case Series of 18 Patients. Clin Neuroradiol. 2024 Sep;34(3):605-611.

Financial disclosures

Financial Disclosures

Reviewers

Ann Tran – Research Funding, Argenyx; Research Funding and Consultant, Genetech