Acne Rosacea

Updated March 2025

Alexis Kassotis and Lora R. Dagi Glass, MD

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- The exact pathophysiology of disease development is uncertain, but is thought to be multifactorial, involving:

- Genetic predisposition (suspected).

- Causative gene(s) have yet to be identified using genomic studies.

- Dysregulation of the immune system.

- Genomic studies have demonstrated increased expression of genes involved in the innate and adaptive immune systems.

- Examples include increased expression of:

- Cathelicidin, which promotes inflammation and angiogenesis.

- Kallikrein 5 (KLK5), a serine protease that cleaves cathelicidin into its active form.

- Toll-like receptor 2, which activates KLK5.

- Colonization with Demodex folliculorum, a saprophytic mite.

- Thought to contribute to pathogenesis by continually stimulating the innate immune system via toll-like receptor 2 and toll-like receptor 4.

- D. folliculorum may colonize the sebaceous glands in otherwise healthy individuals, but is present in significantly higher rates in those with rosacea.

- One multicenter, cross sectional study found the density of D. folliculorum to be nearly 6 times higher in individuals with rosacea than disease-free controls (Casas, 2012).

- Activation of several cellular aberrancies, including nuclear factor kappa B, p38 and ERK kinases, and specific cytokines.

- Common triggers:

- Temperature changes

- Consumption of spicy food, hot beverages, chocolate, caffeine, or alcohol

- Ultraviolet (UV) light

- UV light leads to increased formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

- ROS can activate the KLK5-cathelicidin cascade and are also thought to cause the vasodilatory response seen in rosacea.

- Symptoms may be worsened by irritating topical agents or astringents and a variety of medications (i.e. vitamin B12, amiodarone, and nasal steroids).

- Emotional and psychological stress.

- Genetic predisposition (suspected).

Epidemiology

- Prevalence for rosacea ranges widely across populations and is estimated between 1 and 22% (van Zuuren, 2017).

- Most common in fair skinned individuals of Celtic origin.

- Classically presents in women aged 30-50.

- Phymatous changes are most likely to manifest in males in the 5th to 7th decades of life.

- The male to female ratio of rhinophyma is as high as 30:1 (Fink, 2018).

- Phymatous changes are not seen in the pediatric population.

- Ocular and periocular findings occur in up to 75% of cases (van Zuuren, 2017).

Clinical features

- Diagnostic criteria (National Rosacea Society Expert Committee, 2017):

- Diagnostic phenotypes (the presence of 1 is diagnostic):

- Characteristic pattern of persistent central face erythema (may worsen intermittently)

- Phymatous changes

- Sebaceous gland hypertrophy and fibrosis

- Thickened skin with nodularity

- Most commonly involves the bulb of the nose (rhinophyma)

- Major phenotypes (typically appear with diagnostic phenotypes, but 2 or more major features alone are diagnostic)

- Papules and pustules

- Flushing

- Telangiectasia

- Ocular manifestations

- Eyelid margin telangiectasia

- Scleritis or sclerokeratitis

- Interpalpebral conjunctival injection

- Spade-shaped corneal infiltrates

- Secondary phenotypes (typically appear with 1 or more diagnostic or major phenotypes)

- Facial edema

- Burning or stinging (most commonly in the malar distribution)

- Dryness of the central facial skin

- Ocular manifestations

- Posterior blepharitis caused by meibomian gland dysfunction with recurrent chalazia (Figure 1)

- Formation of a “honey crust” at the eyelid margin with cylindrical collarette of scale at the base of the eyelashes

- Conjunctivitis

- Irregular architecture at the lid margin

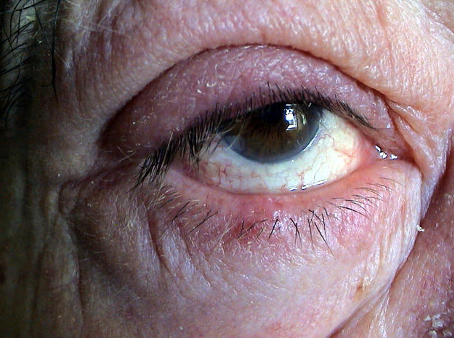

- Periocular erythema (Figure 2)

- Periocular edema

- Dry eye syndrome with related symptoms (i.e. itching, burning, foreign body sensation, epiphora)

- In part due to rapid tear breakup from evaporative tear dysfunction

- 2019 Global Rosacea Consensus (ROSCO)

- Ocular rosacea: margin telangiectasia, blepharitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis and anterior uveitis (Schaller, 2020)

- Diagnostic phenotypes (the presence of 1 is diagnostic):

Other diagnostic tests: none

- Skin biopsy is only beneficial to rule out other diseases, as it is non-specific and varies by phenotype.

Differential diagnosis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Flushing disorders

- Acne vulgaris

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Cutaneous malignancy

- Other forms of blepharitis: seborrheic, staphylococcal, meibomian gland dysfunction without underlying rosacea

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Medical therapy

- Treatments for ophthalmic symptoms:

- Blepharitis:

- Lid hygiene and warm compresses

- Avoid triggers (i.e. alcohol, spicy good, UV)

- Dry eye management

- Lubricating drops, gels, ointments

- Punctal plugs

- Oral omega-3 fatty acids

- Nutritional supplementation using flax seed and fish oil

- Cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion

- Topical treatment

- Azithromycin drops, cyclosporine drops, tacrolimus drops, steroid drops

- Topical metronidazole (applied to the eyelids)

- Oral doxycycline

- Doxycycline should be avoided in children under 8 years of age due to pigment deposition in bones and teeth.

- Oral azithromycin has been used successfully as an off-label alternative to doxycycline.

- It may be used in combination with topical tacrolimus.

- Other oral options:

- Minocycline

- Erythromycin

- Metronidazole

- Cyclosporine

- Surgical therapies:

- Punctal closure

- LipiFlow system

- Intense pulsed light (may be efficacious)

- Intraductal meibomian gland probing

- Treatments for erythema and telangiectasia:

- Conservative management with avoidance of triggers and cold compresses

- Topical alpha-adrenergic agonists (brimonidine or oxymetazoline for erythema)

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors

- Oral beta blockers

- Oral doxycycline

- Laser therapy, intense pulsed light therapy, or electrodessication

- Treatments for papules and pustules:

- Avoidance of triggers

- Topical azelaic acid

- Topical ivermectin

- Topical metronidazole gel

- Topical minocycline

- Oral doxycycline

- Refractory disease:

- Isotretinoin (highly teratogenic)

- Treatments for phymatous features:

- Topical retinoids

- Oral doxycycline

- Oral isotretinoin

- Physical destruction of fibrous tissue (carbon dioxide laser therapy, surgical laser ablation, electrosurgery, electrocautery, dermabrasion, cryotherapy and scalpel excision)

- Maintenance therapy for cutaneous disease:

- Topical metronidazole is the most rigorously studied and frequently used maintenance therapy. It was demonstrated in a placebo-controlled trial to be efficacious in maintaining remission for up to 6 months (Dahl, 1998).

- Topical azelaic acid and ivermectin have also been demonstrated to sustain remission (Stein-Gold, 2014).

- Maintenance therapy for ocular disease involves continuous management of dry eyes (i.e. artificial tears) and lid hygiene.

Prognosis: chronic, relapsing, remitting course

Future directions

An ongoing clinical trial is assessing the impact of topical MAP kinase inhibition in rosacea (clinical trial NCT05616923).

Complications

- Chronic, symptomatic blepharitis

- Vision threatening keratitis with corneal erosions, ulceration, perforation, scarring (rare)

- Psychological morbidity

- Individuals with sustained erythema from rosacea were found in a meta-analysis to have lower scores on validated health related quality of life questionnaires than their disease-free counterparts (Bewley, 2016).

- Anxiety, depression, embarrassment and feelings of stigmatization are frequently reported in this population.

- Significant impediment to work, with subsequent economic considerations.

Photograph attributed to Hellenic Dermatological Atlas.

Figure 1. Ocular rosacea with blepharitis and chalazion on the lower eyelid margin.

Photograph attributed to Hellenic Dermatological Atlas.

Figure 2. Acne rosacea with rhinophyma as well as periocular and central face erythema.

References and additional resources

- Akhyani M, Ehsani AH, Ghiasi M, Jafari AK. Comparison of efficacy of azithromycin vs. doxycycline in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized open clinical trial. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(3):284-288.90.

- Akpek EK, Merchant A, Pinar V, Foster CS. Ocular rosacea: Patient characteristics and follow up. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1863-1867.

- Bewley A, Fowler J, Schöfer H, et al. Erythema of rosacea impairs quality of life: results of a meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther.2016;6:237-247

- Casas C, Paul C, Lahfa M, et al. Quantification of Demodex folliculorum by PCR in rosacea and its relationship to skin innate immune activation. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21(12): 906-910.

- Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, et al. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:679-683.

- Deeks ED. Ivermectin: a review in rosacea. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16(5):447-452

- Fink C, Lackey J, Grande D. Rhinophyma: A Treatment Review. Dermatologic Surgery. 2018; 44(2): 275-282.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: The 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):148-155.

- Gold LS, Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L, et al. Minocycline 1.5% foam for the topical treatment of moderate to severe papulopustular rosacea: Results of 2 phase 3, randomized, clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(5):1166.

- Halioua B, Cribier B, Frey M, Tan J. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:163-168

- Juliandri J, Wang X, Liu Z, et al. Global rosacea treatment guidelines and expert consensus points: The differences. J Cos Dermatol. 2019;18(4):960-965.

- Kroshinsky D & Glick SA. Pediatric Rosacea. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(4):196-201.

- Lane SS, DuBiner HB, Epstein RJ, et al. A new system, the LipiFlow, for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2012;31(4):396‐404.

- Maskin SL, Alluri S. Intraductal meibomian gland probing: background, patient selection, procedure, and perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:1203‐1223.

- Mohamed-Noriega K, Loya-Garcia D, Vera-Duarte GR, Morales-Wong F, Ortiz-Morales G, Navas A, Graue-Hernandez EO, Ramirez-Miranda A. Ocular Rosacea: An Updated Review. Cornea. 2025 Apr 1;44(4):525-537. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000003785. Epub 2025 Jan 14. PMID: 39808113; PMCID: PMC11872267.

- Schaller M, Almeida LMC, Bewley A, Cribier B, Del Rosso J, Dlova NC, Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kautz G, Mannis MJ, Micali G, Oon HH, Rajagopalan M, Steinhoff M, Tanghetti E, Thiboutot D, Troielli P, Webster G, Zierhut M, van Zuuren EJ, Tan J. Recommendations for rosacea diagnosis, classification and management: update from the global ROSacea COnsensus 2019 panel. Br J Dermatol. 2020 May;182(5):1269-1276. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18420. Epub 2019 Oct 16. PMID: 31392722; PMCID: PMC7317217.

- Stein Gold L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Long-term safety of ivermectin 1% cream vs azelaic acid 15% gel in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: results of two 40-week controlled, investigator-blinded trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1380-1386.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

- van Zuuren E. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017: 377(18):1754-1764.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol. 2019; 181(1): 65-79.

- Wladis EJ & Adam AP. Treatment of ocular rosacea. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2018;63(3):340-346.

- Wladis EJ, Aakalu VK, Foster JA, et al. Intense Pulsed Light for Meibomian Gland Disease: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2020;S0161-6420(20)30267-0.

- Wladis EJ, et al. Intense Pulsed Light for Meibomian Gland Disease: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology, 2020; 127:1227-1233.

- Wladis EJ, Iglesias BV, Adam, AP, Gosselin EJ. Molecular Biologic Assessment of Cutaneous Specimens of Ocular Rosacea. Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2012;28(4):246-25.

- Wladis EJ, Lau KW, Adam AP. Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Is Enriched in Eyelid Specimens of Rosacea: Implications for Pathogenesis and Therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;201:72‐81.

- Wladis EJ, Swamy S, Herrmann A, Yang J, Carlson JA, Adam AP. Activation of p38 and Erk Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases Signaling in Ocular Rosacea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(2):843‐848.

- Yelverton C. Topical maintenance therapy for rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2):AB23.

Financial disclosures

Reviewers

Lora Dagi Glass: Consultant, Ora Clinical