Acquired Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

Updated May 2024

Nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) is a blockage of the lacrimal outflow system that may be complete or incomplete with various degrees of tearing, discharge, and infection. NLDO is rarely associated with bleeding. Exquisite pain may accompany acute lacrimal sac distention due to dacryolithiasis and/or dacryocystitis. Mucopurulent discharge is often seen with distal obstruction of the lacrimal sac or duct, while clear tearing is often associated with punctal or canalicular obstruction.

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Involutional stenosis (idiopathic)

- Most common cause of obstruction

- Associated with closure of the lumen by inflammatory infiltrates and edema possibly due to infection or autoimmune disease

- Women are two times more frequently affected then men

- Women have narrower canals than men (McCormick A, et al. The diameter of the nasolacrimal duct measured by computed tomography: gender and racial differences. Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 37: 357-61, 2009 AND Shigeta K, et al. Sex and age differences in the bony nasolacrimal canal: an anatomical study. Arch Ophthalmol, 125: 1677-81, 2007.)

- Dacryolithiasis

- Cast formation within the sac and duct resulting in obstruction

- Consist of shed epithelial cells, lipids and amorphous debris with or without calcium

- Trauma

- Particularly midface and nasal orbital ethmoid (NOE) fractures

- Consider prophylactic silicone intubation in some cases

- Drugs

- Chemotherapy medications

- Taxol derivatives: Docetaxel and Paclitaxel

- 5-Fluorouracil

- Radioactive iodine 131 therapy

- Phospholine iodide ophthalmic drops

- Cholinesterase inhibitor

- Rarely used today

- Idoxuridine ophthalmic drops

- Used for ocular HSV infections

- Canalicular obstruction

- Inflammatory disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), formerly Wegener’s

- Eosinophilic angiocentric fibrosis (EAF)/IgG4-related disease

- Lethal midline granuloma (LMG)

- Neoplasm

- Lymphoma (Figure 1)

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Inverting papilloma

- Sinonasal tumors

Figure 1. Lymphoma.

- Periorbital radiation therapy for malignancies

- Nasal pathology

- Cocaine inhalation abuse

- Tumor

- Prior nasal or sinus surgery

- Iatrogenic damage may occur from maxillary antrostomy with functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS)

- Chronic sinusitis/rhinitis

- Lacrimal plugs (displaced, especially intracanalicular)

- Dental impaction

Epidemiology

- Women are two times more frequently affected than men

- Age

- Babies: congenital NLDO

- Young adults

- Canalicular obstruction/herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection

- Facial trauma (often males)

- Middle age: dacryolith (especially women and smokers)

- Elderly: primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction

History

- Location: unilateral versus bilateral

- Lifestyle effect/functional status

- Onset

- Acute

- Dacrocystitis

- Dacryolithiasis

- Chronic

- Tearing by location

- Indoors without reflex tearing: anatomic block/NLDO

- Outdoors only: often pseudo epiphora/reflex secretion

- “Watery eyes” due to allergy or dysfunctional tearing syndrome

- Timing

- Constant (block/NLDO)

- Intermittent

- Dacryolith, allergy, impacted turbinate

- Partial/incomplete (functional) NLDO

- Tear quality

- Clear tears (punctal/canalicular obstruction)

- Blood-tinged tears (consider tumor)

- Lesion might be at the level of the conjunctiva, lacrimal sac, or lacrimal gland.

- Might be idiopathic

- Also consider menstruation, severe epistaxis, bleeding diathesis, and corneal disease (Ho, VH, et al. Bloody tears of unknown cause: case series and review of the literature. OPRS, 20: 442-7, 2004).

- Copious debris with mattering (stasis/NLDO)

- Prior infections

- Dacryocystitis

- Conjunctivitis (HSV): associated pain/numbness

- Topical and systemic medications

- Previous facial surgery

- Pertinent medical conditions

- GPA

- Systemic inflammatory/rheumatologic disease

Clinical features

- Patients often present with excess tearing, mucopurulent discharge with mattering of the lids and skin.

- Occasionally skin breakdown is present.

- Those with a distended sac may report pain, discharge and sometimes a history of prior cellulitis.

- Intermittent blurred vision often accompanies an enlarged marginal tear strip.

- Red eye

- Elevated marginal tear strip due to reflux and associated ocular irritation

- Normal or low marginal tear strip might be present with a functional obstruction in the elderly with hyposecretion and toxic tears

- Lacrimal sac mass below the medial canthal tendon

- The strong superior aspect of the medial canthal tendon prevents superior extension of the lacrimal sac.

- Tumors above the medial canthal tendon often require imaging.

- Compressible mass with mucoid or mucopurulent reflux: dacryocystitis

- Noncompressible mass

- Painless: Consider neoplasm; imaging is warranted.

- Painful: lacrimal sac mucocele (Figures 2 and 3) +/- facial cellulitis

- Excessive tearing (true epiphora)

- Overflow of tears due to a “plumbing problem”

- Patients present with tissue in hand and might deny allergies and pain.

- Mucopurulent discharge sometimes associated with ocular irritation and red eye

- Blurred vision: Elevated marginal tear strip bothersome with downgaze reading

- Eyelash mattering and crusting: reflux due to outflow obstruction

- Pain due to obstruction causing inflammation from secondary infection including dacryocystitis, dacryocystocele, abscess and sometimes facial cellulitis

- Intermittent tearing partially improved with topical steroids and or antihistamines seen with incomplete/partial nasolacrimal obstruction

- Bloody tears: Consider malignancy.

Figure 2. Mucocele with topical anesthetic cream.

Figure 3. Mucocele drainage.

Testing

Ophthalmic exam

- Visual acuity, pupillary, ocular motility, and slit-lamp biomicroscopy exams

- External exam

- Look for eyelid malpositions, floppy/lax eyelids, facial palsy/synkinesis, incomplete blink, punctal absence, stenosis or eversion, incipient entropion, and trichiasis.

- Measure eyelid laxity/distraction and snapback tests.

- Puncta should not be visible without eyelid eversion.

Slit-lamp exam

- Look for eyelid, corneal, and conjunctival abnormalities such as canaliculitis, symblepharon, giant papillary conjunctivitis, chalazion, and molluscum.

- Evaluate tear quality: tear breakup time (TBUT) and tear film debris.

- Evaluate tear quantity: measure tear meniscus/marginal tear strip (MTS).

- Increased marginal tear strip

- Greater than 0.2 mm by slit beam

- If lower eyelid retraction hinders MTS assessment, hold the lower lid upward near the inferior limbus while using slit-lamp.

Lacrimal-sac palpation

- Palpate for enlarged lacrimal sac or abscess cavity.

- Expression of pus with medial canthal pressure

- A distended sac with mucopurulent reflux to palpation signifies a NLDO. If the nasal exam is normal, DCR is indicated.

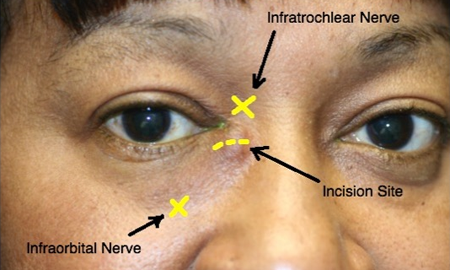

Figure 4. Lacrimal sac abscess incision and drainage.

Nasal evaluation

Assess vestibule and septum.

Inspect for tumor, impacted turbinate, and polyposis/mucosal abnormality.

Physiologic tests

- Dye disappearance test (DDT)

- Procedure

- Instill fluorescein.

- Observe under cobalt blue filter.

- Look for asymmetry of the MTS.

- Persistence of dye or significant asymmetry after 5 minutes indicates an obstruction.

- DDT does not determine site of lacrimal drainage abnormality.

- Site of obstruction determined by inspection of the eyelids, palpation of the lacrimal sac, and irrigation of outflow system

- Interpretation

- Significant delay in clearance time suggests lacrimal obstruction.

- Asymmetric dye disappearance time suggests unilateral obstruction to outflow.

- Jones I test, primary dye test

- The Jones I test evaluates lacrimal outflow under normal physiologic conditions

- Procedure

- Fluorescein is instilled into the conjunctival cul-de-sac followed by placing a cotton-tipped applicator under the inferior turbinate to retrieve dye at 2 and 5 minutes.

- Alternatively, one can look at the posterior pharynx for clearance with a cobalt blue light and a tongue depressor or on a tissue after nose blowing with occlusion of the other nostril.

- Interpretation

- Positive dye recovery indicates a patent nasolacrimal drainage system, although recovery times might be variable, and false-negative results are frequent (up to 1/3rd of patients).

- Positive dye recovery often indicates normal function.

- A negative Jones I test does not differentiate between inadequate physiologic function (functional block) and anatomic obstruction.

- Jones II test, secondary dye test

- Because of the error and technical difficulty associated with performing these clinic procedures, the Jones I and Jones II tests are infrequently used.

- If the Jones I test is negative, the Jones II test can be performed to confirm anatomic patency.

- Nonphysiologic test

- Procedure: The conjunctival sac is cleared of remaining dye and clear saline is irrigated through the nasolacrimal system.

- Interpretation

- Free flow with irrigation suggests normal anatomy, whereas reflux with fluorescein suggests an obstruction.

- Dye retrieved in nose present with partial obstruction at the lower sac or duct

- Clear saline retrieved in the nose is seen with punctal or canalicular obstruction and punctal eversion.

- Reflux through the opposite punctum with dye is seen with common canalicular obstruction.

- Reflux around irrigating cannula is seen with canalicular obstruction.

- Canalicular probing and irrigation

- Nasolacrimal duct probing is not performed in the tearing adult; it is painful and nontherapeutic.

- Nonphysiologic test

- Procedure

- Instillation of topical anesthetic

- Evaluation for punctal stenosis and dilate as needed

- Consider peripunctal local anesthesia with extensive manipulation

- Gentle technique required with careful attention to the flow pattern and palpation of the lacrimal sac to determine the site of the obstruction

- Diagnostic and unlikely a therapeutic test

- Lacrimal irrigation is unnecessary and contraindicated with dacryocystitis, but nasal examination is recommended.

- Interpretation

- Easy cannula placement and irrigation into the nose without reflux

- Patent nasolacrimal duct

- Possible functional obstruction

- Repeat evaluation for reflex hypersecretion.

- Easy cannula placement with combination of reflux and saline into the nose

- Partial obstruction/dacryostenosis

- Functional obstruction

- Easy cannula placement, sac distention, mucoid reflux, and no fluid flow into the nose: complete NLDO

- Difficulty advancing the cannula, reflux of clear saline through the system and no sac distention: common canalicular obstruction

- Difficulty advancing cannula and inability to irrigate: canalicular obstruction

Nasal speculum evaluation of the nose

Imaging studies

Most ASOPRS members do not routinely order imaging for the majority of patients with epiphora (Nagi KS, et al. Utilization patterns for diagnostic imaging in the evaluation of epiphora due to nasolacrimal obstruction: a national survey OPRS, 26: 168-71, 2010).

Consider imaging with

- History of associated bleeding

- Globe displacement

- Abnormal nasal examination

- History of naso-orbital facial fractures, nasal sinus disorders

- Congenital malformations/facial clefts

Special tests

These are not routinely used. Clinical evaluation is often all that is needed.

- Dacryocystography (DCG)

- Nonphysiologic

- Procedure: radiopaque material injected with a syringe through a lacrimal cannula and into each lower canaliculus and imaged radiographically

- This test can identify the level of obstruction and better define the anatomy as well as outline fistulae, diverticulae, mucoceles, neoplasms, and casts of the sac.

- In addition, slow clearance of the dye at 30 minutes can be helpful in confirming the presence of a functional block.

- Dacryoscintigraphy (DSG)

- Nuclear medicine test in which a radioactive tracer used to evaluate nasolacrimal drainage

- Advantages of being noninvasive and physiologic

- Helpful in identifying the site of obstruction, confirming decreased transit time in functional blocks, and quantifying tear drainage

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

Clinical evaluation and occasionally imaging is used to assess the disease stage.

Functional impairment is ascertained by patient history.

Risk factors

- Age

- Smoking

- Surgery near the lacrimal sac/duct

Differential diagnosis

- Upper system obstruction/stenosis

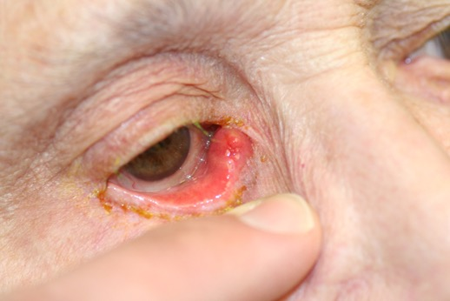

- Canaliculitis (Figure 5)

- Canalicular obstruction

- Eyelid malposition and trichiasis

- Conjunctivitis: giant fornix syndrome

Figure 5. Canaliculitis.

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

See aforementioned sections.

Medical therapy

For an open system versus a functional obstruction/incomplete NLDO, re-examine and assess for reflex hypersecretion.

- Optimize lid hygiene, dry eye and/or allergy treatment.

- Topical steroids to reduce mucosal edema with incomplete obstruction

- Topical antihistamines

- Recheck tear pump

- Apply tape for 1–2 hours while awake and upright to horizontally tighten a lax lower eyelid in a superolateral direction. Evaluate for improvement in tearing.

Radiation therapy

- Useful for management of NLDO secondary to lymphoma and possible management of inflammatory disease

Surgery

- Lacrimal probing and silicone stent placement

- Option for incomplete obstruction

- Sisler trephination for canalicular obstruction

- Balloon dacryoplasty used predominantly for pediatric NLDO

- Lacrimal duct stent

- Poor success rate

- Polyurethane stent, success overseas 18%

- DCR and stent +/- MMC

- External

- Intranasal

- Endoscopic

- Laser

- FESS assisted

- Endonasal

- Transcanalicular laser DCR/Endoscopic

- Recanalize the nasolacrimal duct with endodiathermy bipolar probe

- Adjuvant MMC

Other management considerations

If malignancy is suspected, biopsy lacrimal sac and intranasal lesion.

In the presence of a tumor, DCR might be contraindicated.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

Outcomes are excellent. Success rates of dacryocystorhinostomy range from 63% to 100% (Karim R, et al. A comparison of external and endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy for acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Clin Ophthalmol, 5: 979-89, 2011. Zaidi FH, et al. A clinical trial of endoscopic vs. external dacryocystorhinostomy for partial nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Eye, 25: 1219-24, 2011)

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) leak

- Prevention: imaging, careful rhinostomy, minimize manipulation of the middle turbinate

- Management: repair often with sinus or neurosurgeon

External scar

- Prevention: careful placement within the RSTL

- Management: massage, steroid/5 F-U injections, scar revision

- In one study, 9% of patients rated their external scar as “very visible” and 26% rated it as “moderately visible” (Devoto MH, et al. Postoperative evaluation of skin incision in external dacryocystorhinostomy. OPRS, 20:358–361, 2004.)

Disease-related complications

- Infection

- Chronic conjunctivitis

- Facial cellulitis

- Orbital cellulitis (Figure 6)

- Fistula formation

- Surgical risks

Figure 6. Orbital cellulitis. Consider NLDO in the differential.

Historical perspective

- DCR

- Toti 1904 France

- Lester Jones

References and additional resources

- AAO BCSC Section 7 : Orbit, Eyelids and Lacrimal System

- AAO MOC Exam Study Guide, Oculoplastics and Orbit

- ASOPRS Web Information on the Tear System

- External DCR video, Dr. Rob Bernardino

- External DCR video, Dr. Patrick Boulos

- EyeWiki (TM) Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

- EyeWiki (TM) Dacryocystorhinostomy

- Anijeet, D., Dolan, L., & MacEwen, C. J. (1996). Endonasal versus external dacryocystorhinostomy for nasolacrimal duct obstruction. (D. Anijeet, Ed.). Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Athanasiov, P. A., Madge, S., Kakizaki, H., & Selva, D. (2011). A review of bypass tubes for proximal lacrimal drainage obstruction. Survey of Ophthalmology, 56(3), 252–266.

- Bertelmann E. Rieck P. Polyurethane stents for lacrimal duct stenoses: 5-year results. Graefes Archive for Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 244(6):677-82, 2006 Jun.

- Boulos PR, Rubin PA. A lacrimal sac abscess incision and drainage technique. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008 Sep;126(9):1297-300

- Burkat CN. Lucarelli MJ. Tear meniscus level as an indicator of nasolacrimal obstruction. Ophthalmology. 112(2):344-8, 2005 Feb

- Chung YA. Yoo IeR. Oum JS. Kim SH. Sohn HS. Chung SK. The clinical value of dacryoscintigraphy in the selection of surgical approach for patients with functional lacrimal duct obstruction. [Clinical Trial. Journal Article] Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 19(6):479-83, 2005 Sep

- Cuthbertson FM. Webber S. Assessment of functional nasolacrimal duct obstruction–a survey of ophthalmologists in the southwest. [Journal Article. Multicenter Study] Eye. 18(1):20-3, 2004 Jan

- Devoto MH. Bernardini FP. de Conciliis C. Minimally invasive conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy with Jones tube. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 22(4):253-5, 2006 Jul-Aug.

- Dolman, P. J. (2003). Comparison of external dacryocystorhinostomy with nonlaser endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Ophthalmology, 110(1), 78–84.

- Duffy MT. Advances in lacrimal surgery. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 11(5):352-6, 2000 Oct.

- Eichhorn, K., & Harrison, A. R. (2010). External vs. endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: six of one, a half dozen of the other? Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, 21(5), 396–403.

- Esmaeli, B. (2005). Management of excessive tearing as a side effect of docetaxel. Clinical Breast Cancer, 5(6), 455–457.

- Esmaeli, B., Hidaji, L., Adinin, R. B., Faustina, M., Coats, C., Arbuckle, R., et al. (2003). Blockage of the lacrimal drainage apparatus as a side effect of docetaxel therapy. Cancer, 98(3), 504–507.

- Francisco FC. Carvalho AC. Francisco VF. Francisco MC. Neto GT. Evaluation of 1000 lacrimal ducts by dacryocystography. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 91(1):43-6, 2007 Jan.

- Harris GJ. Sakol PJ. Beatty RL. Relaxed skin tension line incision for dacryocystorhinostomy. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 108(6):742-3, 1989 Dec 15.

- Kashkouli MB. Beigi B. Murthy R. Astbury N. Acquired external punctal stenosis: etiology and associated findings. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 136(6):1079-84, 2003 Dec.

- Lee, D. W. X., Chai, C. H. C., & Loon, S. C. (2010). Primary external dacryocystorhinostomy versus primary endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: a review. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, 38(4), 418–426.

- Massaro BM, Gonnering RS, Harris GJ. Endonasal laser dacryocystorhinostomy: A new approach to nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1172-1176.

- Mazow ML. McCall T. Prager TC. Lodged intracanalicular plugs as a cause of lacrimal obstruction. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 23(2):138-42, 2007 Mar-Apr.

- Pinilla I. Fernandez-Prieto AF. Et al. Nasolacrimal stents for the treatment of epiphora: technical problems and long-term results. Orbit. 25(2):75-81, 2006 Jun.

- Sekhar, G. C., Dortzbach, R. K., Gonnering, R. S., & Lemke, B. N. (1991). Problems associated with conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy. AJOPHT, 112(5), 502–506.

- Watkins, L. M., Janfaza, P., & Rubin, P. A. D. (2003). The evolution of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Survey of Ophthalmology, 48(1), 73–84.

- Woog, J. J., & Sindwani, R. (2006). Endoscopic Dacryocystorhinostomy and Conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 39(5), 1001–1017.