Actinic Keratosis

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Chronic, cumulative sun exposure leading to hyperkeratosis (thickening of keratin layer) and atypical keratinocytes within the basal layer (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Actinic keratosis.

- Actinic keratoses are pre-cancerous lesions that may progress to squamous cell carcinoma

Epidemiology

- More common in the elderly, particularly those with fair complexion and a history of chronic sun exposure

- Affects 11–26% of the United States population (Iorio 2013)

- 4% of men > 40 years old, 34% of men > 70 years old

- 9% of women > 40 years old, 18.2% of women > 70 years old

- Risk of transformation to SCC is 0.1–0.24% per year

- Rate of conversion to invasive SCC is 5–20% over 10–25 years

History

- Chronic sun exposure

- Age

- History of previous skin cancer

- Immunosuppression

- Transplant patients

- HIV

- Pruritus and burning of affected area

Clinical features

- Flat or elevated, scaly, erythematous, keratotic plaque

- Rarely occurs as a single lesion; most commonly there are multiple lesions over a “field”

- Found on sun-exposed areas (face, dorsum of hands, head, neck, forearms)

- Can be pigmented (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Pigmented actinic keratosis.

- Can form a keratin horn

- Sandpapery texture on palpation

- Lesion will vary in size and texture over periods of time depending on the amount of keratinization, which can flake off and reaccumulate

Testing

- Typically actinic keratosis (AK) is a clinical diagnosis and biopsy is not necessary

- Biopsy can be considered in the following situations due to increased risk of a SCC (Dréno 2014)

- Skin is thickened

- > 1 cm

- Induration

- Inflammation

- Ulceration

- Bleeding

- Rapid growth

- Pain on palpation

Risk factors

(Iorio 2013)

- Cumulative ultraviolet radiation

- Sun exposure

- Lack of sunscreen use

- Common in the elderly population because sunscreen was not widely available until the 1950s and its importance not fully realized until more recently

- Proximity to the equator

- Tanning beds and sunbathing

- Fair complexion

- Most commonly Fitzpatrick Type I and II; however, often seen in Type III and even Type IV

- Advanced age

- History of previous SCC and other skin carcinomas

- Immunocompromised state

- Males > females

Differential diagnosis

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Bowen’s disease

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Seborrheic keratosis

- Actinic lentigines (sun spots)

- Melanoctic lentigines

- Melanoma

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

- Given the risk of transformation to SCC, most clinicians favor excision and/or treatment (Lagler, 2012).

Medical therapy

- Advantageous for primary lesion, field areas (large photo-damaged areas common to the scalp and face) (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Actinic keratosis of the scalp.

- Topical 5% 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)

- Inhibits DNA synthesis and RNA transcription

- Mainstay of topical treatment

- Apply cream bid for 2–4 weeks

- Clearance rate is 43–96%; however, up to 65% recur at 12 months

- Reports of successful use on eyelid AK, including margin lesions (Couch 2012)

- 64% resolved with 2-week treatment course

- 46% required additional treatment for recurrence or persistence

- < 15% of the patients had mild ocular problems including mild keratitis and chemosis that resolved with lubrication

- Imiquimod therapy (particularly for extensive facial lesions)

- Toll-like receptor 7 agonist

- Causes release of cytokines and an inflammatory response

- Dosing varies: typical dose is 3 times weekly for 8 hours (overnight) for 4 weeks, followed by 4 weeks of rest and reevaluation

- Higher clinical and histopathologic clearance and decreased rate of recurrence compared to 5-FU and cryosurgery (Krawtchenko 2007)

- They reported a clearance rate of a field at 12 months of 73% for imiquimod, compared to 33% for 5-FU and 4% for cryotherapy

- Dreno et al., however, report a clearance of 55% for two cycles

- Imiquimod has been used for treatment of periocular basal cell carcinoma, however ocular toxicity including irritation and keratitis can limit its use. (Carnero 2010)

- Diclofenac gel

- Nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory drug that inhibits cyclooxygenase pathway

- Causes apoptosis and anti-angiogenesis

- Apply bid for 2–3 months

- Maximum effect is seen 30 days after treatment cessation

- There is only one report on the use on periocular tissue (Batra 2012).

- They obtained clearance in 4/4 patients.

- 50% recurred

- Photodynamic therapy (PDT) (Iorio 2013)

- Apply 5-aminolevulinic acid 3 hours prior to illumination

- Red (630–700 nm) or blue (400–470 nm) light source.

- Typically done in 2 sessions

- Clearance rate at 3 months is reportedly 59%–91% (Dréno 2014)

- Indicated for multiple AK of the face and scalp

- PDT has been used on eyelid BCC with good success (Togsverd-Bo 2009)

- There are limited reports on the use of PDT for periocular AK (Toledo-Alberola 2012)

- They did not report the duration of follow-up.

- They reported good cosmetic result; however, in the postoperative photo there is a significant ectropion. It is difficult to determine if it was present prior to the PDT or if there is a causal relationship, as this issue was not addressed in the manuscript.

- Retinoids might play a role in prevention and treatment of AK; however, a randomized study has not been done (Ianhez 2013)

Surgery

Surgical excision

- A survey of ASOPRS members in 2012 showed that most treat periocular AK with surgical excision (Lagler 2012)

- Useful for treatment of periocular lesions due to the adverse effects of other treatments and possibility of ocular irritation with topical modalities.

- Recurrent lesions carry high risk of squamous cell carcinoma and should be biopsied.

Cryosurgery

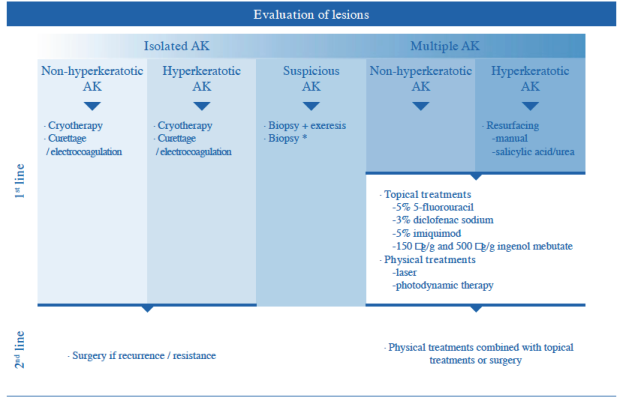

- Generally considered by dermatologists to be the first-line treatment for isolated AKs (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Treatment algorithm proposed by Dréno in 2014.

- No standard treatment. Typically apply for 10–30 seconds until a frozen ring develops.

- Reported clearance rate is highly variable at 67.2–98% (Martin 2010)

- Dreno et al. report:

- Clearance rate at 3 months 68–75% with 1–2 applications

- 5–88% at 24 months with 2 applications

- Risk of recurrence 1.2%–12% within 1 year (Krawtchenko 2007)

- Variable results in the literature due to lack of standardized method and difficulty in determining extent of clinical margins

- Most useful for isolated lesions

- Issues of scarring, hypo- and hyperpigmentation limit its use periocularly

Laser therapies

- Ablative Er:Yag and CO2

- Used for large areas of AKs

- A recent randomized trial showed cryotherapy was superior to CO2 ablative laser in treatment of isolated lesions (Zane 2014).

- Similar response at 3 months; however, few recurrences at 12 months in the cryotherapy group

- Also showed superior results for cryo to thick lesions

- Nonablative fractional Er:Yag and CO2

- Not intended as monotherapy

- Optimizes penetration of topical treatments

- Can be used to decrease the incubation time for PDT (Jang 2013)

Combination of multiple medical and/or surgical therapies

Typically the treatment of AK is directed at isolated lesions as well as treating the field.

Follow-up for regression/progression

(Werner 2013)

- Single lesions without a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) or immunosuppression

- 20–30% regress without treatment

- With treatment, 15–53% recur

- No data available for single lesion in patients who are immunosuppressed or who have history of NMSC

- Field areas

- Regression rate

- Scalp and face is 0–7.2%

- Immunosuppressed 0%

- Recurrence within 12–14 months is 57%

- Data on regression has questionable external validity due to high number of undefined study drop-outs, population differences, and possibility of patient behavior modification including decreased sun exposure and sunscreen use.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Topical 5% fluorouracil

- Extreme photosensitivity expected and normal

- Severe erythema and crusting expected and normal

- Scarring and poor cosmetic outcome

- Careful patient selection and counsel prior to use

- Treatment can be temporarily discontinued if significant reaction occurs

- Mild ocular irritation

Imiquimod therapy

- Similar to 5-FU but not as severe

- Improved cosmetic outcome compared to 5-FU (Krawtchenko 2007)

- Ocular irritation and keratitis

Surgical excision

- Scarring or tissue loss can result in

- Eyelid malposition

- Trichiasis

- Mechanical impairment of lacrimal drainage

- Infection is rare.

- Complications can generally be prevented by careful surgical technique.

Cryosurgery

- Hypo-and hyperpigmentation

- Scarring can occur especially if the freeze is too deep.

- Since no excision occurs, free surgical margins cannot be checked.

Risks of all techniques

- Recurrence or progression to squamous cell carcinoma

- Incomplete removal

- One of the main drawbacks of nonsurgical treatments that can limit their use in the periocular setting

- There is significant dermatology literature documenting success of nonsurgical treatment, but reports of their periocular use are relatively limited.

- Although the risk of recurrence, SCC foci, and progression to SCC is relatively low, it is the opinion of the authors that lesions involving the eyelids often necessitate more aggressive management than similar lesions found on other areas of the face and body.

- Complete excision is more easily justified because of the risk of development of destructive SCC that could result in a large defect and difficult repair.

- This sentiment is seemingly reflected in the survey done by Lagler and Freitag showing a higher rate of excision of AK by ASOPRS members.

- By the same reasoning, it could also be beneficial to use nonsurgical methods on large lesions, potentially sparing the patient a large resection of an in-situ lesion and a complicated repair.

Disease-related complications

Risk of malignant transformation

(Werner 2013)

Rate of progression to SCC is variable, but approximate lifetime risk is 10%.

- Rate of progression is dependent upon several factors

- Presence of multiple vs single actinic keratosis (AK)

- History of other NMSC

- Without history of NMSC: 0.075% per year

- With at least two NMSC: 0.53% per year

- Immunocompetence

- 40% progression in immunosuppressed transplant patients

97% of SCC arise from AK.

Squamous cell carcinoma that develops from an AK is usually very indolent, but can be invasive.

Historical perspective

- The management of AK has changed significantly, shifting from primarily surgical to nonsurgical.

- There are increasing numbers of studies using nonsurgical methods for eyelid lesions, and these techniques will likely continue to increase in the future.

References and additional resources

- American Academy of Dermatology. Dermatology A to Z, Diseases and Treatments, Actinic Keratosis.

- Monograph 8, Surgery of the Eyelids, Lacrimal System, & Orbit, 2nd edition, 2011. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 4: Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors; Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System, 2013-2014. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Ackerman AB, Mones JM. Solar (actinic) keratosis is squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):9-22.

- Batra R, Sundararajan S, Sandramouli S. Topical diclofenac gel for the management of periocular actinic keratosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(1):1-3.

- Black EH, et al. Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2012;580-581.

- Carneiro RC, de Macedo EM, Matayoshi S. Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of periocular Basal cell carcinoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(2):100-102.

- Couch SM, Custer PL. Topical 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of periocular actinic keratosis and low-grade squamous malignancy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(3):181-183.

- Dréno B, Amici JM, Basset-Seguin N, Cribier B, Claudel JP, Richard MA. Management of actinic keratosis: a practical report and treatment algorithm from. AKTeam™ expert clinicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(9):1141-1149.

- Ianhez M, Fleury LF Jr, Miot HA, Bagatin E. Retinoids for prevention and treatment of actinic keratosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(4):585-593.

- Iorio ML, Ter Louw RP, Kauffman CL, Davison SP. Evidence-based medicine: facial skin malignancy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(6):1631-1643.

- Jang YH, Lee DJ, Shin J, Kang HY, Lee ES, Kim YC. Photodynamic therapy with ablative carbon dioxide fractional laser in treatment of actinic keratosis. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25(4):417-422.

- Krawtchenko N, Roewert-Huber J, Ulrich M, Mann I, Sterry W, Stockfleth E. A randomised study of topical 5% imiquimod vs. topical 5-fluorouracil vs. cryosurgery in immunocompetent patients with actinic keratoses: a comparison of clinical and histological outcomes including 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(Suppl 2):34-40.

- Lagler CN, Freitag SK. Management of periocular actinic keratosis: a review of practice patterns among ophthalmic plastic surgeons. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(4):277-281.

- Martin G. The impact of the current United States guidelines on the management of actinic keratosis: is it time for an update? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(11):20-25.

- Salasche SJ. Epidemiology of actinic keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(1 Pt 2):4-7.

- Togsverd-Bo K, Haedersdal M, Wulf HC. Photodynamic therapy for tumors on the eyelid margins. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(8):944-947.

- Toledo-Alberola F, Belinchón-Romero I, Guijarro-Llorca J, Albares-Tendero P. Photodynamic therapy as a response to the challenge of treating actinic keratosis in the eyelid area. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103(10):938-939.

- Werner RN, Sammain A, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, Stockfleth E, Nast A. The natural history of actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(3):502-518.

- Zane C, Facchinetti E, Rossi MT, Specchia C, Ortel B, Calzavara-Pinton P. Cryotherapy is preferable to ablative CO2 laser for the treatment of isolated actinic keratoses of the face and scalp: a randomised clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(5):1114-1121.