Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of the Lacrimal Gland

Updated July 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Research into the oncogenesis of adenoid cystic carcinoma has revealed a low prevalence of mutations in common oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes (Stephens 2013).

- A genetic translocation t(6;9)(q22-23;p23-24) has been identified in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast and head and neck (Persson 2012) that results in a v-myb avian myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog-nuclear factor I/B (MYB-NFIB) gene fusion oncoprotein (Persson 2009).

- The MYB-NFIB oncoprotein is overexpressed in more than 85% of adenoid cystic carcinomas at nonlacrimal sites (Brill 2011).

- The MYB-NFIB fusion gene was found in 7 of 14 lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinomas (ACC) studied and none of 19 non-ACC lacrimal gland tumors (Von Holstein 2013).

- High nuclear expression of MYB RNA was found in 2 lacrimal gland ACCs studied; 3 of the lacrimal gland ACCs without MYB-NFIB fusion had other forms of MYB rearrangement; and all 13 lacrimal ACCs studied had high nuclear expression of the MYB oncogene. RNA and oncoprotein expression remain to be demonstrated more definitively.

- The MYB oncoprotein targets cell growth, apoptosis, transcriptional regulation, and cell cycle control. In the study cited above of 14 lacrimal gland ACCs there was no correlation between patient survival and MYB-NFIB status. It is present in the tumor, but its precise role is not known (Persson 2012).

Epidemiology

- The most common malignant epithelial tumor of the lacrimal gland

- Accounts for 10–15% of epithelial lacrimal gland neoplasms

- Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland accounts for 5–10% of all adenoid cystic carcinomas.

- Adenoid cystic carcinoma accounts for only 1% of head and neck malignancies.

- Less malignant course in children

- No apparent sex predilection

History

- The clinical history helps differentiate between adenoid cystic carcinoma and benign lacrimal gland tumors such as pleomorphic adenoma.

- Pain might be present — would not be typical of a benign tumor.

- Progressive (signs and symptoms present < 1 year) — benign tumors also grow, but more slowly.

- Paresthesias (perineural invasion) would be unusual with a benign tumor, except with long-term compression.

- Ptosis, especially temporally — mass effect can be seen with pleomorphic adenoma, but more pronounced with ACC.

Clinical features

- Proptosis, axial and inferior and medial globe displacement of globe (Figures 1 and 2)

- Ptosis

- Motility disturbance

Figure 1. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. Courtesy Evan H. Black, MD.

Figure 2. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. Courtesy Raymond Cho, MD.

Testing

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Lacrimal fossa mass with bony erosion — typically irregular bony destruction

- Possible apical extension into the superior orbital fissure

- Less well circumscribed lesion than benign mixed tumor

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is useful to define posterior extension of the lesion further (Figure 3)

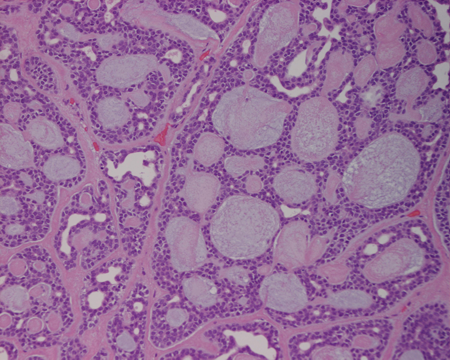

- Pathology — lesion is nonencapsulated and infiltrating, indicating need for incisional biopsy (Figure 4).

- Histologically, adenoid cystic carcinomas are subtyped into tubular, cribriform, or basaloid growth patterns (solid). Most show mixed histology.

- Basaloid variant has more aggressive biologic behavior and is associated with overall shorter survival.

- Bone invasion is frequently (about 75%) evident on initial staging.

Figure 3. MRI of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Courtesy Raymond Cho, MD.

Figure 4. Adenoid cystic carcinoma slide. Courtesy Raymond Cho, MD.

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

Staging — 6th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM definitions for carcinoma of the lacrimal gland:

- Tx Primary tumor cannot be assessed.

- T0 No evidence of primary tumor

- T1 Tumor ≤ 2.5 cm in greatest dimension limited to the lacrimal gland

- T2 Tumor ≤ 2.5 cm in greatest dimension invading the periosteum of the fossa of the lacrimal gland

- T3 Tumor between 2.5 and 5 cm in greatest dimension (T3a limited to the lacrimal gland, T3b invades the periosteum.)

- T4 Tumor > 5 cm in greatest dimension (T4a invades the orbital soft tissue, optic nerve, or globe without bone invasion. T4b invades the orbital soft tissue, optic nerve, or globe with bone invasion.)

- NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

- N0 No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1 Regional lymph node metastasis

- Mx Distant metastasis cannot be assessed

- M0 No distant metastasis

- M1 Distant metastasis

AJCC seventh edition:

- In the sixth edition, small tumors (< 2.5 cm — T1 versus T2) and medium tumors (2.5–5-cm — T3a versus T3b) were classified depending on whether they have invaded through the periostium to local bone;

- Large tumors (> 5 cm) were most likely to be T4b with bone invasion

- In the seventh edition, tumors of any size with bone or periosteal involvement are classified as T4. Separation in this newer classification system is based on size.

- T1 = tumor 2 cm or smaller

- T2 = tumor 2–4 cm in size

- T3 = tumor greater than 4 cm

- T4 = bone or periosteal invasion

- T4a = periosteal invasion

- T4b = bone invasion

- T4c = invasion of adjacent structures including brain and sinuses

Frequent staging patterns:

- Staging helps predict outcome; in a recent review of 53 patients, using the 6th edition classification, 38 (72%) had > T3 tumors at presentation (Ahmad 2009).

- In that series, seventeen (45%) of the 38 patients with > T3 tumors and only 1 (7%) of the 15 patients with < T3 tumors died of disease during the study period, during median follow-up of 94 months (7.9 years; 95% confidence interval, 50–120 months) (Ahmad 2009).

- Nodal metastasis is less frequent with this tumor; invasion is most commonly intracranial and of the adjoining bone (Von Holstein 2013).

- Distant metastasis is not commonly recognized on initial staging; about 10% of cases (Williams 2010).

Staging was compared using the 6th versus 7th classification system (El-Sawy 2012).

- Because periosteal and bone invasion are so common at presentation with adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland a significant percentage of patients are upstaged when using the seventh vs the sixth edition classification system (5% versus 80% had T4 disease in this study of 18 patients).

Differential diagnosis

Inflammatory lesions of the lacrimal gland

- Idiopathic orbital inflammation

- Sjogren syndrome

- Sarcoid

- Infectious dacryoadenitis

Lymphoid lesions

- Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia

- Atypical lymphoid hyperplasia

- Lymphoma

Epithelial tumors

- Malignant mixed tumor

- Benign mixed tumor

Bony destructive lesions

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Actuarial survival is less than 50% at 5 years after diagnosis and 20% at 10 years, regardless of treatment regimen.

- The neoplasm tends to invade nerves and lymphatic channels resulting in microscopic spread and distant disease regardless of local treatment.

- Local recurrence is also common despite aggressive surgical and radiotherapeutic intervention.

- There is a propensity for intracranial extension via the lacrimal nerve through the superior orbital fissure and intracranial involvement is the principal cause of death.

- Bone and lung are sites of distant metastasis.

Medical therapy options

Chemotherapy has proven of limited value and therefore is used in an adjuvant or neoadjuvant role rather than as primary treatment. The same is true of targeted molecular therapy (LeTourneau 2011).

Radiation therapy options

- Adjuvant postoperative external beam radiotherapy is recommended at a dose of 60 Gy in 30 fractions to the primary tumor site.

- Because of the high frequency of perineural invasion and intracranial extension, additional stereotactic radiosurgery can be applied for evident or suspected intracranial and skull base involvement.

- The decision to administer preoperative radiotherapy (to shrink the primary tumor) can be made in concert with the radiation oncologist, oncology consultant, and tumor board when available.

- Even with aggressive surgical excision and adjuvant radiotherapy, local recurrence will occur in 10–15% of cases; the recurrence might be in the regional lymph nodes, the skin, or the bone beyond the region of treatment with radiotherapy.

- This is particularly true with basaloid phenotype.

- About half of patients will develop distant metastasis within 1 year of initial staging — specifically those with basaloid tumors.

- Adjuvant systemic postoperative chemotherapy might be indicated for patients with basaloid tumors.

- In children with tumors that lack basaloid features or neural invasion on histopathologic examination, a globe-sparing procedure augmented with orbital plaque brachytherapy has been used.

- There has been no formal study of proton beam radiation therapy for lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma.

- Anecdotal experience with lacrimal ACC and studies of nonlacrimal ACC suggest superior local tumor control and tissue sparing.

- Proton beam radiation therapy is particularly considered when treating intracranial extension (Pommier 2006).

- Protons have equivalent effectiveness to photons, but less extension to surrounding healthy tissues, allowing for higher dose delivery to the tumor at its margin.

Surgical therapy options

- Incisional biopsy with examination of permanent sections

- There are no controlled studies or data to suggest that aggressive surgery prolongs life.

- Globe-sparing en-bloc resection

- Generally requires significant tissue excision that will limit ocular motility and visual function

- Orbital exenteration is preferred by some.

- Orbital exenteration with additional bone removal is considered a more aggressive excision.

- Orbitocranial resection (Wilson 2011):

- Coronal incision and frontotemporal craniotomy to expose the orbital roof and lateral orbital wall

- Dura is dissected away from the roof of the orbit.

- Osteotomies are created in the superior and lateral orbital rims.

- The superior osteotomy extends posteriorly to the orbital apex.

- The lateral osteotomy, at the junction of the lateral wall and the orbital floor, extends posteriorly to the sphenoid wing.

- The optic nerve and contents of the superior orbital fissure are clamped, and exenteration is performed.

- Lacrimal gland fossa bone, including limited anterior orbital roof and lateral orbital wall, should be removed with soft tissue excision regardless of surgical procedure chosen.

- Invasion of the bony cortex and/or periostium will be evident on histology in about 80% of cases, regardless of preoperative imaging.

- Tumors are upstaged based on the histologic finding of periosteal or bony involvement.

Other management considerations

- Cytoreductive intra-arterial chemotherapy in conjunction with exenteration and adjuvant IV chemotherapy and radiation therapy (not to be used alone) has been advocated.

- In one study (AJO 2006; 141:44), the cumulative 5-year carcinoma cause-specific death rate was 16.7% in the intra-arterial cytoreductive chemotherapy group compared with 57.1% in the conventional treatment group. The cumulative 5-year recurrence rate in the IACC treated group was 23.8% compared with 71.4% in the conventional treatment group.

- Ten year survival — 100% in intra-arterial cytoreductive group (n = 8 pts) versus 50% for those who could not complete the protocol (n = 11 pts) (Von Holstein 2013)

Common treatment response patterns, follow-up and secondary treatment strategies

Careful follow-up and imaging are the mainstay, monitoring for tumor recurrence.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Deformity is associated with both exenteration and globe sparing surgery:

- Includes loss of vision and eye movement even with globe sparing surgery

- Requires lubrication and supportive care

- Consider orbital prosthesis after exenteration.

Disease-related complications

- Chronic pain due to perineural disease might require pain management.

- Metastatic spread, usually bone and lung, typically within 1–3 years of presentation, needs systemic monitoring; there is no specific treatment.

- Local recurrence or intracranial spread — evident by progression of tumor size on imaging — might be treated with additional radiotherapy.

Historical perspective

Surgery for lacrimal gland malignancies, particularly adenoid cystic carcinoma, was reviewed in the mid-1980s looking back over a 130 years (Henderson 1986).

- Mortality remained high throughout this period, essentially unchanged despite technological advance.

- In 1964, subclinical bone invasion was suggested as a possible cause of tumor recurrence after surgery, prompting a recommendation for radical bone removal combined with exenteration (Reese 1964).

- This evolved toward increasingly aggressive surgical excision including monobloc excision of the orbit, leaving exposed dura, and severing the optic nerve at the chiasm.

- In 1992, John Wright observed that extension beyond the orbit was common even after aggressive primary surgical excision, suggesting that the tumor invaded early beyond these surgical planes. He observed that survival was significantly greater when tumor resection was combined with radiotherapy (Wright 1992).

References and additional resources

- Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Organization International (ACCOI)

- Ahmad SM, Esmaeli B, Williams M, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer classification predicts outcome of patients with lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(6):1210-1215.

- Brill LB, Kanner WA, Fehr A, et al. Analysis of MYB expression and MYB-NFIB gene fusions in adenoid cystic carcinoma and other salivary neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(9):1169-1176.

- El-Sawy T, Savar A, Williams MD, De Monte F, Esmaeli B. Prognostic accuracy of the seventh edition vs. sixth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor classification for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(5):664-666.

- Henderson JW. Past, present and future surgical management of malignant epithelial neoplasms of the lacrimal gland. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70(10):727-731.

- LeTourneau C, Razak AR, Levy C, et al. Role of chemotherapy and molecularly targeted agents in the treatment of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(11):1483-1489.

- Persson M, Andren Y, Mark J, et al. Recurrent fusion of MYB and NFIB transcription factor genes in carcinomas of the breast and head and neck. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(44):18740-18744.

- Persson M, Andren Y, Moskaluk CA, et al. Clinically significant copy number alterations and complex rearrangements of MYB and NFIB in head and neck adenoid cystic carcinomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51(8):805-817.

- Pommier P, Liebsch NJ, Deschler DG, et al. Proton beam radiation therapy for skull base adenoid cystic carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(11):1242-1249.

- Reese AB, Jones IS. Bone resection in the excision of epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964;71:382-385.

- Stephens PJ, Davies HR, Mitani Y, et al. Whole exome sequencing of adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(7):2965-2968.

- Tse DT, et al. Long-term outcomes of neoadjuvant intra-arterial cytoreductive chemotherapy for lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(7):1313-1323.

- Tse DT, Benedetto P, Dubovy S, Schiffman JC, Feuer WJ. Clinical analysis of the effect of intraarterial cytoreductive chemotherapy in the treatment of lacrimal gland adenoid cystic carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(1):44-53.

- Von Holstein SL, Fehr A, Persson M, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland: MYB gene activation, genomic imbalances and clinical characteristics. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):2130-2138.

- Williams MD, Al-Zubidi N, Debnam JM, et al. Bone invasion by adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland: preoperative imaging assessment and surgical considerations. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(6):403-408.

- Wilson KF, Ward PD, Spector ME, Marentette LJ. Orbitocranial approach for treatment of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(6):397-400.

- Wright JE, Rose GE, Garner A: Primary malignant neoplasms of the lacrimal gland. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76(7)401-407.