Blepharitis, Meibomitis, and Hordeola

Updated August 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Chronic lid margin inflammation is likely multifactorial

- Staphylococcal blepharitis

- Chronic colonization with low grade infection and/or inflammatory reaction to bacterial antigens and toxins

- Includes aerobic and anaerobic species – Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Propionibacterium acnes, Corynebacterium

- Seborrheic blepharitis

- Mechanical obstruction caused by scaling of eyelid margin

- Cyclical process with obstruction causing inflammatory changes of the eyelid

- From overproduction of sebum, causing greasy scaling

- Demodicosis

- Demodex mites are common incidental inhabitants of lash follicles.

- Mites may introduce bacteria or primarily exacerbate inflammation.

- Mites are frequently seen in eyelid colarettes (Gao, 2005).

- Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD)

- Similar processes cause inflammation of the posterior eyelid margin.

- Altered meibomian gland secretions result in gland blockage.

- Decreased lipid layer in tear film and abnormal lipids contribute to ocular and eyelid inflammation and dry eyes.

- Can be associated with rosacea or seborrheic dermatitis

- Chalazion

- Plugging/inspissation of a meibomian or Zeis gland results in trapping of sebaceous material.

- The trapped material elicits inflammation, typically granulomatous.

- May have an infectious component, as described for staph blepharitis

- Staphylococcus aureus is most common pathogen

- Lash sampling was performed to microscopically count mite populations

- In 44 adult and 47 pediatric patients with chalazia and 34 adult and 30 pediatric age- and sex-matched patients without chalazia (Liang, 2014)

- Demodicosis was defined as presence of mites, present in 69% of chalazion patients, compared with 20% of controls.

- Demodex brevis was significantly more prevalent than demodex folliculorum in patients with chalazia.

- Chalazia with demodicosis had signficantly more common recurrence after excision

- Patients with past history of rosacea were excluded from the study.

- Terminology can be confusing – hordeolum is inspissation and infection of sebaceous glands

- Anterior lid (glands of Zeis, lash follicles): external hordeolum or stye

- Posterior lid (meibomian glands): internal hordeolum

Epidemiology

- Blepharitis

- May be changing as the epidemiology of staph species continues to change

- Role of community acquired MRSA is increasingly important

- Older literature suggested that staphylococcal disease occurs in younger individuals (McCulley 1985)

- Overall, blepharitis incidence increases in incidence with age (Driver 1996)

- In 1982, 590,000 patient visits were due to blepharitis (NDTI 1982).

- Blepharitis is observed in 37–47% of ophthalmologists’ and optometrists’ practices (Hom 1990, Lemp 2009)

- Keratoconjunctivitis sicca was found to be associated in 25–50% of cases (McCulley 1982 and 1985).

- Chalazia occurs in all ages, races, and sexes.

History

- Blepharitis and meibomitis

- Burning, itching, and foreign body sensation

- Usually worse in the morning

- Redness of the eyelids

- Crusting of the eyelids

- Filmy, blurred vision

- Recurrent chalazia/hordeola

- Chalazia

- Acute inflammation: rapid onset, mild pain, focal tenderness, and erythema

- Resolution can occur prior to the development of the chronic phase.

- Can fluctuate in size

- Can spontaneously drain posteriorly or anteriorly

- Blurred vision secondary to induced astigmatism with lid swelling

- Chronic form can follow, consisting of a painless, well-circumscribed mass within the tarsal/pretarsal eyelid

- Can present with pyogenic granuloma as mass or bleeding

Clinical features

- Blepharitis

- Hard scales and crusts around eyelid cilia called “sleeves” or “collarettes.”

- Staphylococcal debris and white blood cells congealed together and colonization by Demodex folliculorum (Favier, 2017)

- Seborrheic inflammation causes oily or greasy crusting

- There is a 95% incidence of associated seborrheic dermatisis (McCulley 1985). Manifests as yellow crusting also on eyebrows and scalp

- Erythema and telangiectasis of eyelid margins

- Poliosis

- Madarosis

- Trichiasis

- About 1/3 have keratoconjunctivitis sicca (Edwards 1987)

- Ocular surface inflammation can cause abnormal tear meniscus, abnormal tear break up time, foamy discharge, debris in tear film

- Conjunctival hyperemia and papillary reaction of tarsal conjunctiva

- Corneal changes such as punctate epithelial keratopathy, marginal infiltrates, phlyctenules

- Notching and thickening of the eyelid

- Meibomian gland dysfunction or meibomitis

- Inflammation of posterior lid margin

- Eyelid margin irregularity, scalloping, and thickening

- Prominent telangiectasis

- Pouting or plugged meibomian gland orifices

- Turbid, thick secretions (“toothpaste-like”)

- Foamy tear meniscus

- Conjunctival hyperemia, and often papillary reaction

- Corneal changes such as punctate epithelial keratopathy, marginal infiltrates, pannus

- Can have margin rounding, notching, dimpling, thickening, irregularity

- Arita et al (2016) developed a grading scale to describe severity of meibomitis

- Telangiectasia – 0 = no findings; 1 = mild telangiectasia; 2 = moderate telangiectasia or redness; 3 = severe telangiectasia or redness.

- Meibomian gland collapse – 0 = minimal; 1 = moderate; 2 = severe

- Irregularity, plugging, foaming, and thickness (each graded separately) – 0 = none; 1 = mild; 2 = severe.

- Gland dropout was the most consistent evidence of severity.

- Chalazia

- Overlying skin can have erythema

- Important to evert eyelid; nodule on the tarsal conjunctival surface

- Loculation of inflammatory material can cause chronic cyst-like nodule

- Can localize anteriorly

- Elevated nodules may be near lid margin or up to 10 mm away (upper eyelid)

- Surrounding edema, erythema might indicate treatment for preseptal cellulitis

Testing

- Usually diagnosed clinically

- Several techniques to quantify meibomian gland dropout:

- Meiboscopy — clinical examination with transilluminated biomicroscopy of the glands (Robin 1985)

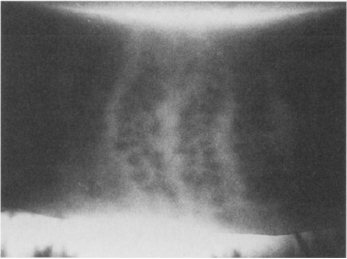

- Meibography — near-infrared light and camera capture images of the glands (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Top: Meibography of a normal eyelid. Bottom: Abnormal dilation of meibomian glands in a patient with meibomian gland dysfunction.

- Confocal microscopy

- Cultures are generally not helpful

- Yield is higher with frank purulence

- Staph epidermidis may be interpreted as normal flora even if clinically significant

- Culture for MRSA can support treatment, if oral antibiotics prescribed for acute signs of infection

- Demodex mites can be visualized by epilating lash, place on a glass slide, add a drop of fluorescein, place cover slip (Kheirkhah, 2007)

- Histopathologic confirmation of demodicosis for atypical, persistent, or recurrent lesions.

Risk factors

Blepharitis

- Dry eye syndrome

- Dermatologic conditions: e.g., seborrheic dermatitis

- Rosacea

- Oral retinoid therapy

- Demodicosis

- Giant papillary conjunctivitis

Chalazia/Hordeola

- Rosacea

- Chronic posterior blepharitis (meibomian gland dysfunction)

- Demodex might be a risk factor (Yam 2014).

Differential diagnosis

Malignant tumors

- Sebaceous gland carcinoma

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Merkel cell carcinoma (Rawlings 2007)

- Hemangioendothelioma (Al-Faky 2011)

- Plasmacytoma (Maheshwari 2009)

- Renal cell carcinoma (Tailor 2008)

- Pleural mesothelioma (Tsina 2006)

Benign tumors

- Pleomorphic adenoma (Ramlee 2007)

- Granular cell tumor (Scruggs 2014)

- Solitary neurofibroma (Shibata 2012)

- Plexiform neurofibroma (Tey 2006)

- Pilomatrixoma (Katowitz 2003)

- Keratoacanthoma

- Papilloma

- Ruptured epithelial inclusion cyst

Inflammatory disorders

- Sarcoidosis

- Atypical mycobacterial infection

- Wegener granulomatosis (Ismail 2007)

- Ruptured epithelial inclusion cyst

- Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E (Job) syndrome (Destefano 2004, Crama 2004)

Infectious

- Preseptal cellulitis

- Canaliculitis (Almaliotis 2013)

- Tuberculosis (Mittal 2013)

- Leishmaniasis (Rahimi 2009)

Other

- Retained soft contact lens (Agarwal 2013)

- Trichilemmal cyst (Meena 2012)

- Lacrimal gland duct stones (Kim 2014)

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Blepharitis

- Chronic, with periods of exacerbation and remission

- Can begin in childhood, although typically onset is in middle age

- If severe, can cause eyelash loss, scarring of eyelids, trichiasis, secondary corneal scarring

- Chalazia

- Typically self-limiting, resolving in 1–2 weeks

- Chronic form may develop which can take many months to years to resolve.

- Eventually, virtually all chalazia resolve, even after years (Honda 2010).

Medical therapy

Blepharitis

- Eyelid hygiene

- Warm compresses

- Scrubs with water, dilute baby shampoo or commercially available eyelid wipes once or twice daily depending on severity

- Olenik study (Olenik 2013):

- Randomized double-blinded trial of baby-shampoo eyelid cleaning and preservative-free artificial tears with placebo or 1.5 gram of a composition (DHA, EPA, vitamins A, C, and E, tyrosine, cysteine, glutathione, zinc, copper, manganese, selenium, DPA)

- Measurements of staining, tear breakup time, Schirmer test, eyelid inflammation, ocular surface disease index (OSDI), meibomian gland expression

- After 3 months (64 patients), there was significant improvement of OSDI, TBUT, eyelid margin inflammation, meibomian gland expression, Schirmer test.

- For staphylococcal blepharitis treat with topical antibiotics, for example, erythromycin or bacitracin ophthalmic ointment

- Topical azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1%

- Has anti-inflammatory properties

- Studies have shown improvement for anterior and posterior blepharitis — open label studies (John 2008, Luchs 2008, Haque 2010, Opitz 2011).

- Dosing schedules are varied – 1 gtt BID x 2 days, then qday for 7–28 days (Opitz 2012)

- A multicenter, randomized study comparing Tobradex ST (4x/day x 14 days) to Durasite (2x/day x 12 days) for blepharitis favored Tobradex (Torkildsen 2011)

- Ivermectin cream 1% can reduce demodecosis (Favier, 2017)

- Ivermectin can be administered orally at a dose of 200 mcg/kg once, repeated in 7 days

- Reduces demodex folliculorum in refractory blepharitis (Holzchuh, 2011)

- Available as 3 mg tablet – 170 lb. (77 kg) adult would take 15 mg or five pills

- Minocycline or doxycycline 50–100 mg BID can be considered for chronic meibomitis

- Can taper to qday after the first month

- Slow-release formulation (50 mg qday) might be effective

- Alternatives include tetracycline 500 mg BID or azithromycin 250–500 mg, 1–3x/week; or 1g qweek x 3 weeks (caution in patients with cardiac conduction abnormalities)

- Treatment based on small clinical trials on symptoms improvement with ocular rosacea (Frucht-Pery 1993, Sobolewska 2014)

- Evidence of improving blepharitis symptoms (Dougherty 1991, Shine 2003)

- Short course of topical corticosteroids can be used when inflammation is severe.

- Eyelid thermal pulsation system (LipiFlow)

- Device uses pulsatile “milking” movements and application of heat to each eyelid

- A single treatment (12 minutes) can have improvement in ocular surface disease index (OSDI).

- Has been shown to be more effective than heat (warm compresses) alone

- No randomized controlled studies

- Xdemvy (lotilaner 0.25%, Tarsus Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA) was approved in 2023 for the treatment of Demodex blepharitis.

- 6-week treatment course, administered as 1 drop two times per day into the affected eye.

- GABA-receptor inhibitor that directly targets the parasite causing paralysis and eventual death of the mite.

Meibomitis

- 150 patients with clinical evidence of meibomitis were randomized into three groups, treated for one month with doxycycline 200 mg BID, doxycycline 20 mg BID, or placebo (Yoo, 2005).

- The study did not assess lid changes.

- Both treatment groups had improvement in tear breakup time and Shirmer test, compared with placebo.

- Quaterman reported improvement in eyelid inflammation at 12 weeks in open label trial of doxycycline 100 mg daily for 12 weeks (Quaterman, 1997).

- Aronowicz (2006) treated 16 meibomitis patients with 50 mg minocycline daily for 2 weeks, followed by 10 weeks of 100 mg daily.

- Assessed appearance of the eyelids, degree of meibomian gland plugging and amount of secretion

- Noted improvement in eyelid margin thickening and vascularization

- Decrease in eyelid margin debris and less meibomian gland obliteration

- Effect continued three months after cessation of the medication.

- Igami (2011) treated 13 meibomitis patients who had not responded to topical corticosteroids and antibiotics with oral azithromycin.

- In 3 cycles of 500 mg/day for 3 consecutive days at 7-day intervals

- Using eyelid scoring system that measured severity of eyelid debris, telangiectasias, mucous secretion, and eyelid margin edema and erythema

- Found clinical improvement, except eyelid edema, thirty days after completion of therapy

- Once weekly azithromycin, 1 gram orally for three weeks, was assessed in 32 patients with meimobitis, using subjective improvement as the primary end point (Greene, 2014).

- Concurrently continued treatment with topical steroid drops and compresses

- At mean 5 week follow-up 75% reported symptomatic improvement

- GI upset was the most common side effect (9%)

- Literature assessment by the American Academy of Ophthalmology concluded that there is no level I evidence to support use of oral antibiotics including doxycycline, minocycline or azithromycin for meibomian gland related ocular suface disease (Wladis, 2016).

Chalazia/Hordeola

- Warm compresses and eyelid massage

- Eyelid hygiene/scrubs

- Topical antibiotics may be of value in treating staphylococcal blepharitis component.

- Systemic antibiotics are active against Staphylococcus aureus for accompanying preseptal cellulites.

- Systemic tetracyclines for treatment of chronic accompanying meibomitis, rosacea

- Topical or systemic tetracyclines can help improve meibomian secretions.

- Topical steroid can be used to decrease inflammatory component of skin (although not demonstrated in any studies).

Surgery

Blepharitis

- Intraductal meibomian probing (that is, Maskin probe) (Maskin 2010)

- Topical anesthetic or injected local anesthetic placed into the eyelid

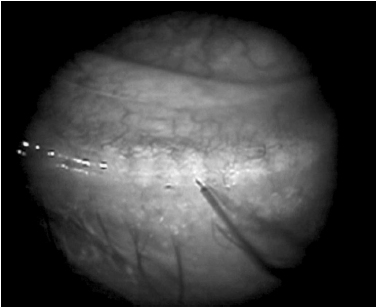

- Start with 2-mm probe (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Maskin probe usage. Penetration through orifice with 2-mm probe. Note hemorrhage at orifice of adjacent gland.

- Can encounter resistance at meibomian gland orifice and within gland (fibrovascular tissue)

- Normal to have droplet of blood at orifice

- Then repeat with 4-mm probe

- Can be also done with hyfrecation tip (Figure 3) (Wladis 2012)

- Anatomic changes resulting in trichiasis or entropion might require surgical correction.

Figure 3. Meibomian probing. Image courtesy Edward J. Wladis, MD.

Chalazia/Hordeola

- Intralesional/perilesional corticosteroid injection

- Can be used for small marginal lesions or other lesions

- Multiple randomized controlled studies assessing injection versus excision (Ben Simon 2011, Goawalla 2007, Jacobs 1984)

- Can have similar rates of resolution, although Jacobs reported much higher rate of complete resolution with surgery (60% versus 8.7%)

- Multiple injections may be needed

- Can use 40 mg/mL or 10 mg/mL triamcinolone and inject 0.05 to 0.15 cc

- Most studies do not use a chalazion clamp at time of injection.

- Surgical drainage via a transconjunctival or cutaneous route

- Anesthetic

- Especially with small lesions, consider marking the skin prior to injection; otherwise, the location of the chalazion can be masked after infiltration.

- Consider using a pledget with 4% lidocaine (plain) between the globe and chalazion to help dull the pain of injection.

- Incision and curettage

- Chalazion clamp is placed on the eyelid to isolate the chalazion, and the eyelid is everted.

- Bard Parker #15 or #11 blade is used to make a stab incision through the posterior tarsal plate.

- Can be vertical or an “x;” some surgeons excise the flaps of the “x;” others leave them.

- Liquid and gelatinous material is expressed.

- Curettage can be performed with a chalazion curette.

- Excise granulomatous tissue and cyst wall especially in chronic forms with little or limited liquid/gelatinous material

- Caution to prevent violation of the skin.

- Cutaneous excision

- In cases of cutaneous changes (erythema, infiltration, thinning), limited excision of skin might be needed to resolve the lesion.

- Use caution in dark-pigmented patients because the visible scar can be more pronounced.

- Because the source of the chalazion is in the tarsal plate, this must also be addressed in addition to the skin.

- Trephination

- Through the conjunctival surface, a “punch” biopsy trephine can be used (Leachman).

- With the trephine (2–5 mm diameter), center it over the visible lesion, and then slowly rotate the trephine while applying pressure.

- Be careful to prevent penetration past the tarsal plate.

- Once through the full thickness of tarsus, use scissors and forceps to excise.

- Margin lesions

- Some suggest marginal curettage (Dubey).

- After placement of an appropriately sized clamp, the curette is placed into the chalazion and curetted.

- The remainder of the proximal chalazion is approached in the “standard” fashion.

- Care should be taken not to communicate the 2 areas to prevent notching.

- Combined excision and corticosteroid injection

- After excision is completed, some authors advocate for intratarsal injection of steroid.

- Best done with clamp in place to prevent embolization of steroid material

- Biopsy for recurrent or atypical lesions

- Caution for any atypical lesions in either appearance or history

- Concern for malignancy or other atypical lesions

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Topical corticosteroids

- Increased intraocular pressure, cataract, infection

- Prevent by using lowest strength and dose possible for only brief period when inflammation severe

Systemic tetracyclines

- Photosensitization, gastrointestinal (GI) upset, azotemia, candidiasis

- Use is contraindicated in children and pregnant or nursing women.

- Taper based on clinical response and use the lowest dose possible.

- Cases of doxycycline induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome have been reported (Cac, 2007; Lau, 2011).

- Pseudotumor cerebri has been reported (Winn 2007).

Pyogenic granuloma formation

- Occurs in the presence of an underlying chalazion/hordeolum

- After excision of pyogenic granuloma, also excise the chalazion.

Globe perforation

- Results in severe visual loss

- Perforation during excision — 2 cases (Shiramizu 2004)

- Perforation during injection — 1 case (Hosal 2003)

Eyelid margin scarring or notching

- Use care when removing tissue at or near the lid margin because there is a risk for eyelid scarring or notching.

- Can revise severe scar or notch with full-thickness pentagonal wedge resection

- Horizontal scarring of tarsal plate

- Some suggest prevention by making only vertical incisions along meibomian gland.

- Make an enlarged excision of involved tarsus to prevent vertical shortening of eyelid.

- Repeated episodes or surgical treatments can lead to posterior lamellar scarring and misdirected eyelashes or eyelash loss.

Damage to surrounding meibomian glands

- Prevent by making vertical cuts through tarsal conjunctival surface.

Intralesional corticosteroid injection for chronic lesions (chalazion)

- Skin depigmentation

- Maintain deep (intratarsal or suborbicularis oculi) level of medication.

- Caution in dark-skinned patients

- Visible steroid (white sediment of triamcinolone) (Cohen 1979)

- Maintain deep (intratarsal or suborbicularis oculi) level of medication.

- Embolization of steroid to retina

- Extremely rare — 2 case reports (Yagci 2008, Thomas 1986)

- Consider use of chalazion clamp during injection to prevent emboli.

Damage to punctum or canaliculus

- Use caution when excising peripunctal or pericanalicular chalazia.

- If punctum or canaliculus is violated, repair with silicone stent intubation.

Disease-related complications

Blepharitis

- Corneal neovascularization and scarring

- Madarosis

- Trichiasis, marginal entropion

- Cicatricial entropion

- Chalazion

- Reflex epiphora

- Can have increased association with some inflammatory diseases, psychologic conditions, hypothyroidism, cardiovascular disease (Nemet 2011)

Chalazia/Hordeola

- Rarely eyelid scarring with or without trichiasis

- Eyelid malposition (for example, ptosis from longstanding lesion of upper eyelid)

- Recurrent lesions

- Preseptal/orbital cellulitis — with superinfection

Patient instructions

Blepharitis

- Cure is often not possible eyelid hygiene will likely need to be performed indefinitely.

- Intermittently, the patient might need more aggressive therapy with topical or systemic medications.

- Return for recurrence of symptoms

- Follow-up in 3 to 4 weeks when symptoms severe and new medication is started

Chalazia/Hordeola

- Prevention of new chalazia with warm compresses, eyelid hygiene

- Return if chalazion/hordeolum recurs

Historical perspective

- Meibomian glands first described by Heinrich Meibomius in 1666 (Meibomius)

- Blepharitis first described by Elschnig in 1908 (Mathers 1991)

- Radiation therapy has been described, without support of clinical trials

References and additional resources

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Cornea/External Disease Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern Guidelines. Blepharitis. 2013. Available at aao.org/ppp.

- Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 4: Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors; Section 6: Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System; Section 8: External Disease and Cornea, 2013-2014. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Focal Points: Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Blepharitis, Module 10, 1989. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Monograph 8, Surgery of the Eyelids, Lacrimal System, & Orbit, 2nd edition, 2011. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Agarwal PK, Ahmed TY, Diaper CJ. Retained soft contact lens masquerading as a chalazion: a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2013;61(2):80-81.

- Al-Faky YH, Al Malki S, Raddaoui E. Hemangioendothelioma of the eyelid can mimic chalazion. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(3):142-143.

- Almaliotis D, Nakos E, Siempis T, et al. A para-canalicular abscess resembling an inflamed chalazion. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2013;618367.

- Arita R, Minoura I, Morishige N, et al: Development of definitive and reliable grading scales for meibomian gland dysfunction. Am J Ophthalmol 2016; 169:125-137.

- Aronowicz JD, Shine WE, Oral D, et al. Short term oral minocycline treatment of meibomianitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2006;90:856–60.

- Ben Simon GJ, Rosen N, Rosner M, Spierer A. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection versus incision and curettage for primary chalazia: a prospective, randomized study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(4):714-718.

- Cac NN, Messingham MJ, Sniezek PJ, Walling HW. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by doxycycline. Cutis 2007; 79:119-122.

- Cohen BZ, Tripathy RC. Eyelid depigmentation after intralesional injection of a fluorinated corticosteroid for chalazion. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88(2):269-270.

- Crama N, Toolens AM, van der Meer JW, Cruysberg JR. Giant chalazia in the hyperimmunoglobulinemia E (hyper-IgE) syndrome. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2004;14(3):258-260.

- Destefano JJ, Kodsi SR, Primack JD. Recurrent Staphylococcus aureus chalazia in hyperimmunoglobulinemia E (Job’s) syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(6):1057-1058.

- Dougherty JM, McCulley JP, Silvany RE, Meyer DR. The role of tetracycline in chronic blepharitis: inhibition of lipase production in staphylococci. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2970-2975.

- Driver PJ, Lemp MA. Meibomian gland dysfunction. Surv Ophthalmol. 1996;40(5):343-347.

- Dubey R, Wang LW, Figueira EC, et al. Management of marginal chalazia: a surgical approach. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:590-597.

- Edwards RS. Ophthalmic emergencies in a district general hospital casualty department. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:938-942.

- Favier C. Demodex clusters. Ophthalmology 2017; 124:1474.

- Frucht-Pery J, Sagi E, Hemo I, Ever-Hadani P. Efficacy of doxycycline and tetracycline in ocular rosacea. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:88-92.

- Gao YY, Di Pascuale MA, Li W, et al. High prevalence of Demodex in eyelashes with cylindrical dandruff. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46(9):3089–3094.

- Goawalla A, Lee V. A prospective randomized treatment study comparing three treatment options for chalazia: triamcinolone acetonide injections, incision and curettage and treatment with hot compresses. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35(8):706-712.

- Greene JB, Jeng BH, Fintelmann RE, et al: Oral azithromycin for the treatment of meibomitis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014; 132:121-122.

- Greiner JV. A single LipiFlow thermal pulsation system treatment improves Meibomian gland function and reduces dry eye symptoms for 9 months. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37(4):272‑278.

- Haque RM, Torkildsen GL, Brubaker K, et al. Multicenter open-label study evaluating the efficacy of azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1% on the signs and symptoms of subjects with blepharitis. 2010;29:871‑877.

- HolzchuhFG, Hida RY, Moscovici BK, et al: Clinical treatment of ocular demodex folliculorum by systemic ivermectin. Am J Ophthalmol 2011; 151:1030-1034.

- Hom MM, Martinson JR, Knapp LL, et al. Prevalance of Meibomian gland dysfunction. Optom Vis Sci. 1990;67:710‑712.

- Honda M, Honda K. Spontaneous resolution of chalazion after 3 to 5 years. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36(4):230‑232.

- Hosal BM, Zilelioglu G. Ocular complication of intralesional corticosteroid injection of a chalazion. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2003;13(9‑10):798‑799.

- Igami TZ, Holzchuh R, Osaki TH, et al. Oral azithromycin for treatment of posterior blepharitis. Cornea 2011;30:1145–9.

- Ismail AR, Theaker JM, Manners RM. Wegener’s granulomatosis masquerading as upper lid chalazion. Eye (Lond). 2007;21(6):883‑884.

- IovienoA, LambiaseA, MiceraA, etal. In vivo characterization of doxycycline effects on tear metalloproteinases in patients with chronic blepharitis. Eur J Ophthalmol 2009;19:708–16.

- Jacobs PM, Thaller VT, Wong D. Intralesional corticosteroid therapy of chalazia: a comparison with incision and curettage. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:836‑837.

- John T. Use of azithromycin ophthalmic solution in the treatment of chronic mixed anterior blepharitis. Ann Ophthalmol. 2008;40(2):68‑74.

- Katowitz WR, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Pilomatrixoma of the eyelid simulating a chalazion. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2003;40(4):247‑248.

- Kheirkhah A, Blanco G, Casas V, Tseng SC. Fluorescein dye improves microscopic evaluation and counting of Demodex in blepharitis with cylindrical dandruff. Cornea 2007;26(6): 697–700.

- Kim SC, Lee K, Lee SU. Lacrimal gland duct stones: misdiagnosied as chalazion in 3 cases. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49(1):102‑105.

- Lane SS, DuBiner HB, Epstein RJ, et al. A new system, the LipiFlow, for the treatment of Meibomian gland dysfunction. 2012;31:396‑404.

- Lau B, Mutyala D, Dhaliwal D. A case report of doxycycline-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Cornea 2011; 30:595-597.

- Leachman JW, Boynton JR, Levin DB. Chalazion management by tarsus trephination. Ophthalmic Surg. 1978;9(1):89‑90.

- Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States: a survey based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf. 2009;7(Suppl 2):S1‑S14.

- Liang L, Ding X, Tseng SCG. High prevalence of demodex brevis infestation in chalazia. Am J Ophthalmology 2014; 342-348.

- Lindsley K, Matsumura S, Hatef E, Akpek EK. Interventions for chronic blepharitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD005556.

- Luchs J. Efficacy of topical azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1% in the treatment of posterior blepharitis. Adv Ther. 2008;25(9):858‑870.

- Maheshwari R, Maheshwari S. Extramedullary plasmacytoma masquerading as chalazion. 2009;28(2‑3):191‑193.

- Maskin SL. Intraductal Meibomian gland probing relieves symptoms of obstructive Meibomian gland dysfunction. 2010;29(10):1145‑1152.

- Mathers WD, Shields WJ, Sachdev MS, et al. Meibomian gland dysfunction in chronic blepharitis. 1991;10:277‑285.

- McCulley JP, Dougherty JM, Deneau DG. Classification of chronic blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89(10):1173‑1180.

- McCulley JP, Dougherty HM. Blepharitis associated with acne rosacea and seborrheic dermatitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1985;25(1):159‑172.

- Meena M, Mittal R, Saha D. Trichilemmal cyst of the eyelid: masquerading as recurrent chalazion. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2012;261414.

- Meibomius H. De Vasis Palpebrarum Novis Epistola Muller, Helmstadt, 1666.

- Mittal R, Tripathy D, Sharma, Balne PK. Tuberculosis of eyelid presenting as a chalazion. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(5):e1‑4.

- National Disease and Therapeutics Index (NDTI), IMS America, Dec 1982.

- Nemet AY, Vinker S, Kaiserman I. Associated morbidity of blepharitis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1062‑1068.

- Nichols JJ, Berntsen DA, Mitchell GL, et al. An assessment of grading scales for meibography images. 2005;24:382‑388.

- Olenik A, Jimenez-Alfaro I, Alejandre-Alba N, Mahillo-Fernandez I. A randomized, double-masked study to evaluate the effect of omega‑3 fatty acids supplementation in Meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Interventions Aging. 2013;8:1133‑1138.

- Opitz DL, Tyler KF. Efficacy of azithromycin ophthalmic solution for treatment of ocular surface disease from posterior blepharitis. Clin Ep Optom. 2011;94(2):200‑206.

- Opitz DL, Harthan JS. Review of azithromycin ophthalmic 1% solution (AzaSite) for the treatment of ocular infections. Ophthalmol and Eye Dis. 2012;4:1‑14.

- Ozdal PC, Codere F, Callejo S, et al. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of chalazion. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(2):135‑138.

- Papas A, Singh M. The effect of a unique omega‑3 supplement on dry mouth and dry eye in Sjogrens patients. ARVO Annual Meeting. 2007.

- Peralejo B, Beltriani V, Bielory L. Dermatologic and allergic conditions of the eyelid. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:137‑168.

- Pinheiro MH Jr, Dos Santos PM, Dos Santos RC, et al. Oral flaxseed oil (Linum usitatissimum) in the treatment for dry-eye Sjogren’s syndrome patients. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70:649‑655.

- Quarterman MJ, Johnson DW, Abele DC, et al. Ocular rosacea. Signs, symptoms, and tear studies before and after treatment with doxycycline. Arch Dermatol 1997;133:49–54.

- Rahimi M, Moinfar N, Ashrafi A. Eyelid leishmaniasis masquerading as chalazia. Eye (Lond). 2009;23(3):737.

- Raju VK, Raju LV, Kheirkah A. Demodex blepharitis. Ophthalmology 2012; 119-200.

- Ramlee N, Ramli N, Tajudin LS. Pleomorphic adenoma in the palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland misdiagnosed as chalazion. 2007;26(2):137‑139.

- Rawlings NG, Brownstein S, Jordan DR. Merkel cell carcinoma masquerading as a chalazion. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42(3):469‑470.

- Robin JB, Jester JV, Nobe J, et al. In vivo transillumination biomicroscopy and photography of Meibomian gland dysfunction: a clinical study. Ophthalmology. 1985;82:1423‑1426.

- Scruggs RT, Black EH. Granular cell tumor masquerading as a chalazion: a case report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;31(1):e6‑8.

- Sherman RS, Hogan MJ. Radiation therapy in diseases of the eye. California Medicine. 1954;80(2):83‑90.

- Shibata N, Kitagawa K, Noda M, Sasaki H. Solitary neurofibroma without neurofibromatosis in the superior tarsal plate simulating a chalazion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(2):309‑310.

- Shine WE, McCulley JP, Pandya AG. Minocycline effect on meibomian gland lipids in meibomianitis patients. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:417‑420.

- Shiramizu KM, Krieger AE, McCannel CA. Severe visual loss caused by ocular performation during chalazion removal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(1):204‑205.

- Sobolewska B, Doycheva D, Deuter C, et al. Treatment of ocular rosacea with once-daily low-dose doxycycline. 2014;33(3):257‑260.

- Tailor R, Inkster C, Hanson I, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma presenting as a chalazion. Eye (Lond). 2008;21(4):564‑565.

- Tey A, Kearns PP, Barr AD. Plexiform neurofibroma masquerading as a persistent chalazion – a case report. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(8):946‑948.

- Thomas EL, Laborde RP. Retinal and choroidal vascular occlusion following intralesional corticosteroid injection of a chalazion. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:405‑407.

- Torkildsen GL, Cockrum P, Meier E, et al. Evaluation of clinical efficacy and safety of tobramycin/dexamethasone ophthalmic suspension 0.3%/0.05% compared to azithromycin ophthalmic solution 1% in the treatment of moderate to severe acute blepharitis/blepharoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(1):171‑178.

- Tsina EK, Papioannou D, Matsouka FO, Kosmidis PA. Metastatic pleural mesothelioma initially masquerading as chalazion. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(7):921‑922.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Stafety Communication. Azithromycin (Zithromax or Zmax) and the risk of potentially fatal heart rhythms. Available at fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm341822.htm.

- Winn BJ, Liao YJ, Horton JC. Intracranial pressure returns to normal about a month after stopping tetracycline antibiotics. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125(8):1137‑1138.

- Wladis EJ, et al. Intense Pulsed Light for Meibomian Gland Disease: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology, 2020; 127:1227-1233.

- Wladis EJ. Intraductal Meibomian gland probing in the management of ocular rosacea. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:416‑418.

- Wladis EJ, Bradley EA, Bilyk JR, el al: Oral antibiotics for meibomian gland-related ocular surface disease: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2016; 123:492-496.

- Wojtowicz JC, Butovich I, Uchiyama E, et al. Pilot, prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an omega‑3 supplement for dry eye. 2011;30:308‑314.

- Yagci A, Palamar M, Egrilmez S, et al. Anterior segment ischemia and retinochoroidal vascular occlusion after intralesional steroid injection. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24(1):55‑57.

- Yam JC, Tang BS, Chang TM, Cheng AC. Ocular demodicidosis as a risk factor of adult recurrent chalazion. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014;24(2):159‑163.

- Yoo SE, Lee DC, Chang MH. The effect of low-dose doxy- cycline therapy in chronic meibomian gland dysfunction. Korean J Ophthalmol 2005;19:258–63.