Botulinum Toxin in Facial Aesthetics

Updated May 2025

Goals

- Reduction of dynamic facial rhytids, which occur secondary to the actions of muscles of facial expression

- Botulinum toxin is not particularly effective for static rhytids, which are secondary to facial skin aging changes or soft tissue devolumization.

- Strategic and selective weakening of facial musculature to alter facial contours to achieve a more symmetric or aesthetically pleasing facial appearance

Pharmacology

- Neurotoxin produced by the gram-positive anaerobe Clostridium botulinum

- In the peripheral nervous system, the toxin acts on the neuromuscular junction, specifically on the presynaptic terminal.

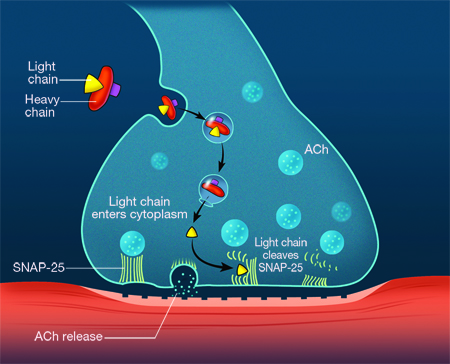

- Interferes with soluble N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins, thereby reversibly inhibiting the release of acetylcholine; results in temporary muscle weakening/paralysis (Niemann, Barinaga, Sollner) (Figure 1)

- Seven serotypes, A through G

- Human tissue is susceptible to A, B, E, F, and G.

- Only types A and B are FDA-approved for injection in the United States (Coffield, Aoki).

- Type A toxins

- Cleave synapsomal-associated protein (SNAP-25) (Blasi)

- Approved for both aesthetic and functional use — the focus of this article

- Longer half-life (and duration of action) compared to other serotypes

- Type B toxins

- Act on vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP) synaptobrevin, a membrane protein of small synaptic vesicles (SSVs) (Schiavo)

- Approved only for functional uses (i.e., cervical dystonia)

- Patients can expect to notice the effects of the toxin in 1–3 days, with a maximum effect occurring in 1–4 weeks. Average duration of effect is 3–4 months (1Carruthers).

Figure 1. Schematic illustrating the mechanism of botulinum toxin type A at the neuromuscular endplate. Once the neurotoxin complex has been endocytosed, the light chain cleaves synaptic neural-associated protein (SNAP-25), thereby inhibiting fusion of Ach vesicles to the cell membrane and preventing release of Ach into the neuromuscular junction.

Type A preparations

- Active toxin present in all type A formulations is a 150 kDa molecule.

- The various type A preparations differ with regard to the presence and relative amount of associated complexing proteins, which serve to stabilize the compound’s structure (Hambleton, Inoue, Ohishi, Chen).

- Type A preparations available in North America (Figure 2)

- OnabotulinumtoxinA — BOTOX® Cosmetic (Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA)

- Original type A formulation; most widely used and studied

- Produced as a vacuum-dried powder

- 150 kDa toxin with complexing proteins plus human albumin and NaCl

- FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe glabellar lines and crow’s feet

- AbobotulinumtoxinA — Dysport® (Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Scottsdale, AZ)

- Dysport®: BOTOX® dose ratio approximately 3:1

- Produced as a lyophilized powder

- 150 kDa toxin with complexing proteins plus human albumin and lactose

- FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe glabellar lines

- IncobotulinumtoxinA — Xeomin® (Merz Pharmaceuticals, Frankfurt, Germany)

- Xeomin®: BOTOX® dose ratio approximately 1:1

- Produced as a lyophilized powder

- 150kDa toxin plus human albumin and sucrose; free of complexing proteins (in theory, may confer a reduced risk of sensitization and antibody formation) (Jost; Frevert)

- FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe glabellar lines

- DaxibotulinumtoxinA-lanm – Daxxify™ (Revance Therapeutics)

- FDA approved 9/2022

- 150 kDa toxing with a proprietary synthetic stabilizing peptide (RTP004)

- Advertised as having a 6-month duration of action

- All type A preparations are widely used off-label for the treatment of other dynamic facial rhytids as well as for facial contouring.

- Comparative studies of the different preparations

- Few large randomized studies have directly compared the various type A formulations. Only a few small studies have been done which suggest certain potential distinctions.

- Studies done in patients with hyperhidrosis and cervical dystonia have suggested that Dysport® may diffuse more into surrounding tissues in comparison to BOTOX®, which could potentially lead to unwanted effects (Ranoux, Simonetta).

- Several studies have suggested that BOTOX® and Xeomin® possess similar efficacies, durations, and safety profiles, including 2 randomized trials (Sattler, Prager).

- DAXXIFY is the newest Type A formulation on the market. It has been shown to be effective for 6 months compared to 3 months of efficacy provided by other Type A formulations.

- DAXXIFY daxibotulinumtoxinA-lanm – (Revance Therapuetics, Nasheville, Tennessee)

- DAXXIFY: BOTOX dose ratio are not interchangeable and units cannot be compared to or converted into units of any other botulinum toxin products

- Produces as a lyophilized powder

- 150kDa plus stabilizing peptide. Should be avoided in patients who have adverse reaction to other botulinum toxins. FDA-approved for the treatment of moderate to severe glabellar lines in adult patients

- The take-away is that an experienced clinician with good knowledge of facial musculature anatomy who is familiar with the potential adverse effects of the toxin (and how to avoid them) should be able to obtain good consistent results with any of the type A toxin preparations.

Figure 2. The 3 type A toxin preparations available for injection in the United States. A and B: OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox); C and D: AbobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport); E and F: Incobotulinumtoxina (Xeomin).

Etiology

- Aging is characterized by volume deflation, facial descent and surface irregularities in the skin.

- Dermal fillers treat volume loss, improve facial support, and reduce skin irregularities.

- Scars may also be treated with soft-tissue fillers.

- Use of an injectable agent for cosmetic enhancement was reported in 1899 by Robert Gersuny, who injected paraffin to create a testicular prosthesis (Kontis, Facial Plast Surg 2009). Materials with better biocompatibility are now available.

Epidemiology

- Age-related volume loss and skin surface irregularities

- Severity of aging relates to intrinsic factors (genetics) and extrinsic factors of ultraviolet exposure, smoking, diet and lifestyle choices.

- Society favors a youthful appearance. Improved facial appearance contributes to psychological well-being and to positive social function.

Facial esthetic uses and contraindications

Aesthetic uses

- Reduction of dynamic facial rhytids

- Horizontal forehead lines

- Vertical glabellar lines

- Lateral canthal lines (crow’s feet)

- Lines on dorsolateral nose (bunny lines)

- Vertical perioral lines

- Melomental folds (marionette lines)

- Addressing Other Facial Aesthetic Issues

- Brow ptosis

- Elevation achieved by targeting the brow depressors

- Gingival/”gummy” smile

- Patients with high/excessive gingival display during smiling due to hyperfunctioning upper lip elevating muscles

- Chin dimpling and horizontal chin crease

- Caused by a combination of mentalis muscle contraction and aging changes (collagen loss and fat atrophy)

- Platysmal bands

- Seen especially in thin patients

Contraindications

- Relative

- Chronic neuromuscular disease (e.g., myasthenia gravis, Eaton-Lambert Syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis)

- A patient taking a drug which interferes with neuromuscular transmission (e.g., cholinesterase inhibitors, magnesium sulfate, aminoglycosides) (Jaspers)

- Absolute

- Overt infection at the desired injection site

- Confirmed hypersensitivity to any component of product

- All type A botulinum toxin preparations are pregnancy class C drugs and therefore should be avoided in pregnant and breast-feeding women

Preprocedure evaluation

Patient history

- Have patient identify areas of concern.

- History of previous surgery or filler treatment

- Current medications and supplements, especially blood thinners and anti-platelet agents

- Medical history and allergies including prior response and reactions to similar products, underlying autoimmune disease, HSV infection and pregnancy

- Identify underlying psychiatric disorders such as Body Dysmorphic Disorder, an underdiagnosed and underreported condition

- Informed consent should be obtained.

Clinical examination

- Inspect the facial skin for signs of breakdown or infection.

- Assess the face at rest and inspect movement and relative strength of the muscles of interest; this information will help guide treatment dosages.

- Observe for signs of pre-existing facial weakness and structural changes, which could potentially be exacerbated by injections and lead to unwanted effects (brow ptosis, lagophthalmos, facial droop), e.g., a patient with blepharoptosis or dermatochalasis may use frontalis muscle contraction to elevate the brow and help lift the eyelid margin or excess skin to a level above the visual axis. Targeting the frontalis for the purpose of reduction of horizontal forehead rhytids will hinder this compensatory behavior, resulting in an unhappy patient.

Testing

- Photographs to document before and after treatment

- Skin testing for allergy not generally indicated except for historic materials such as bovine collagen

Alternative treatments

In general, alternative treatments are variable, depending on the cosmetic indication/goal.

As discussed in other sections, certain rhytids may be more amenable to injection of fillers or a combination of botulinum toxin and fillers. In general, static and deeper rhytids are more effectively addressed with these strategies.

Additional available skin rejuvenation techniques appropriate for certain patients include chemical and laser skin resurfacing modalities.

Surgery (e.g., brow lift, midface lift, rhytidectomy, neck lift) is an effective, albeit more invasive, option for motivated patients who are good surgical candidates.

Observation is always a reasonable option and must be considered, particularly when patient expectations are not realistic.

Storing, reconstituting Type A preparations

Manufacturer storage instructions

- Storage prior to reconstitution

- OnabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX® Cosmetic) and AbobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport®) require refrigeration at 2° to 8°C

- IncobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin®) may be stored at room temperature at 20 to 25°C, in a refrigerator at 2 to 8°C, or in a freezer at -20 to -10°C for up to 36 months

- Storage after reconstitution

- Manufacturers for all toxins recommend that after reconstitution, the toxins should be stored in a refrigerator at 2 to 8°C and administered within 24 hours.

- Many studies have shown that reconstituted toxin can be stored under refrigeration for extended periods of time (up to 6 weeks in 1 study) without reduced efficacy or bacterial contamination (Hexsel, Hui, Lizarralde)

Reconstitution/dilution

- The recommended diluent is nonpreserved sterile normal saline. Bacteriostatic saline can also be used to reduce injection discomfort.

- Dilution volume and final concentration

- Package insert suggested dilutions

- BOTOX® and Xeomin®: 2.5 mL of saline for a 100 unit vial or 1.25 mL of saline for a 50 unit vial, both of which result in a final concentration of 4 units/0.1 mL

- Dysport®: 2.5 mL or 1.5 mL of saline for the 300 unit vial, resulting in a final concentration of 10 units/0.08 mL and 10 units/0.05 mL, respectively

- Practically speaking, because the periocular and facial regions tend to require very precise administration of small doses of toxin over a small area, it may be preferable to use a more concentrated solution.

- For example, in the case of BOTOX® and Xeomin®, using 1 mL of saline to reconstitute a 100 unit vial, giving a concentration of 100 units/1 mL or 1 unit/0.01 mL. In this situation, if the clinician is using a 1 mL syringe, each 0.01 mL “tick” on the syringe corresponds to 1 unit of toxin.

- Clinicians should tailor the specific dilution concentration after taking into account the indicated treatment, personal preference, and experience.

- With regard to Dysport® and Xeomin®, which are produced as lyophilized powders, it is important to fully invert the vial during reconstitution because the particles are distributed throughout the vial and some may become trapped near the rubber stopper at the top of the vial. Failure to invert may result in an underconcentrated solution, which may lead to suboptimal treatment (decreased efficacy or duration).

Techniques, dosages, patterns

Anesthesia

- Not routinely used, but some patients may request topical anesthesia

- Options include

- Skin cooling with

- Ice

- Cooling machines

- Cryospray

- Topical anesthetic creams

- Mixtures of lidocaine and prilocaine are common.

General injection technique

The skin should be cleaned with alcohol prior to injection.

Needle depth depends on the area being treated and the skin thickness in that area:

- Around the eyelids, which have the thinnest skin in the body, injection should be very superficial.

- Deeper injection is required around the thick skin of the glabellar region.

Once the desired needle depth and location has been achieved, the toxin should be injected slowly to both deliver the precise desired dose and reduce patient discomfort.

Injection patterns

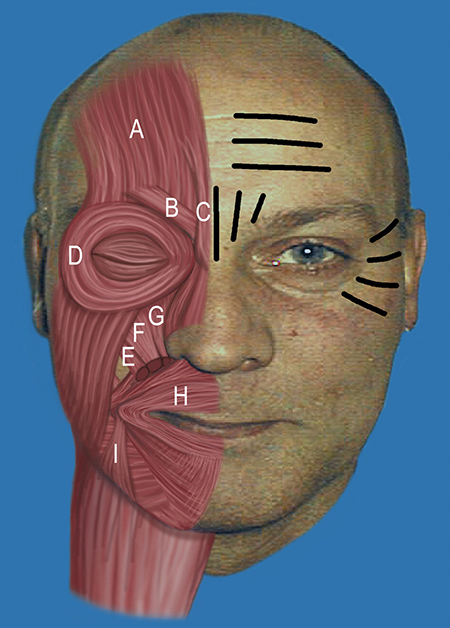

Generally speaking, toxin should be directed at the muscle causing the undesirable wrinkle or contour, not directed at the wrinkle itself (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Accentuated dynamic rhytids (on patient’s left), including horizontal forehead lines, glabellar furrows, and lateral canthal lines. Facial musculature typically targeted by toxin (on patient’s right), including A: Frontalis; B: Corrugator supercilii; C: Procerus; D: Orbicularis oculi; E: Zygomaticus minor; F: Levator labii superioris; G: Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi; H: Orbicularis oris; and I: Depressor angulus oris.

Injection dosages

Need to be tailored to the patient (and therefore will require a “start low, go slow” titrating approach), however there are generalized advised injection dosages for the different targeted muscles

The clinician must also be aware of gender differences in dosing, due to a larger muscle volume in males, which generally requires more units of toxin to achieve the same result as females

Indication-specific strategies and sample injection

Dosages mentioned here pertain to BOTOX® and Xeomin®; a 2.5:1 to 3:1 adjustment would need to be made for Dysport®).

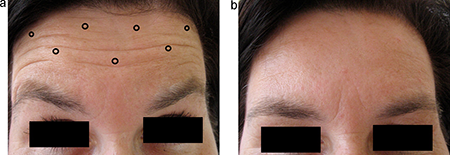

Horizontal forehead lines (Figure 4)

Target the frontalis.

Typical dosage:

- Goal is to weaken but not completely paralyze the brow (“frozen” brow).

- Recommended dosage is 6 to 15 units over 4 to 8 injection sites.

- Certain studies have shown better results with higher doses (24 units) (Carruthers).

Maintain a distance of about 1 to 2 cm above the supraorbital rim to avoid brow ptosis.

Figure 4. (a) Sample injection pattern for the treatment of horizontal forehead lines, targeting the frontalis muscle. (b) 2 weeks after injection, demonstrating frontalis weakening and reduction of horizontal lines.

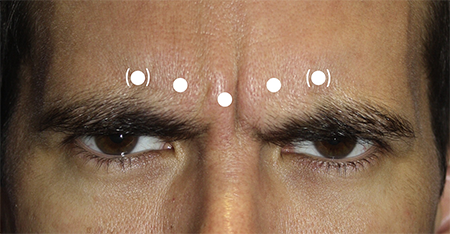

Vertical glabellar lines (Figure 5)

Deeper injection: Target the superficial procerus and deeper corrugator supercilii.

Typical dosage:

- Some clinicians elect to start low with starting dosages of 10 to 30 units for women and 20 to 40 units for men.

- Others believe this area requires a higher treatment dose, using dosages of 20 to 40 units for women and 40 to 80 units for men.

Usually 5 sites are injected.

Care should be taken to avoid injecting below the supraorbital rim because this could lead to toxin migration inferiorly to affect the levator, leading to blepharoptosis.

Figure 5. Sample injection pattern for the treatment of vertical glabellar lines, targeting the procerus and corrugator supercilii.

Lateral canthal lines (crow’s feet) (Figure 6)

Target the orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi; superficial injection

Typical dosage: 10 to 30 units for women and 20 to 30 units for men over 2 to 5 injection sites

Maintain a distance of 1 to 1.5 cm lateral to the lateral orbital rim to minimize weakening of the palpebral portion of the orbicularis oculi, which may lead to lagophthalmos or dry eye.

Medial migration may also affect the levator, resulting in eyelid ptosis.

Avoid injecting below the level of the zygoma to avoid weakening of the zygomaticus major, which may result in mouth droop.

Figure 6. Sample injection pattern for the treatment of lateral canthal lines (crow’s feet), targeting the orbicularis oculi.

Lines on dorsolateral nose (bunny lines)

Target the nasalis.

Typical dosage:

- A single injection of 2 to 4 units on each side of the nasal dorsum about 1 cm superior to the alar groove

- Occasionally, a midline injection is also performed.

More inferior injection may affect the levator labii superioris or alaeque nasi, leading to lip droop.

Vertical perioral lines (Figure 7)

Target the orbicularis oris.

Typical dosage:

- Because this area is prone to significant functional issues — drooling, difficulty eating/drinking — treatment should be very conservative

- Start with a very low dose of 0.5 to 1 unit, then titrate.

At or within 5 mm of the vermilion border, 4 injection points are recommended in the upper lip and 2 in the lower (Semchyshyn).

Avoid treating patients who use their orbicularis oris to play musical instruments or sing.

Because of the nature of the wrinkles and the inability to use large doses, this area may be best treated with adjunct modalities such as soft tissue fillers.

Figure 7. Sample injection pattern for the treatment of vertical perioral lines, targeting the orbicularis oris at (or within 5 mm of) the vermilion border.

Melomental folds (marionette lines) (Figure 8)

Target the depressor anguli oris.

Typical dosage: 3 to 5 units injected at the mandible level at the posterior portion of the depressor anguli oris and at the anterior edge of the masseter

Injections that are either too anterior or too high may weaken the depressor labii inferioris muscle, leading to oral incontinence issues similar to those discussed above in the treatment of vertical perioral lines.

Figure 8. Sample injection pattern for the treatment of Gingival/”gummy” Smile.

Brow lift

Brow elevation is achieved by treating the glabellar area (see above) as well as the superolateral orbicularis oculi (approximately 5 units; gives additional elevation to the tail of the brow), both of which contribute to brow depression.

In these patients, it is beneficial to avoid treating horizontal forehead rhytids with frontalis injections to maximize brow height.

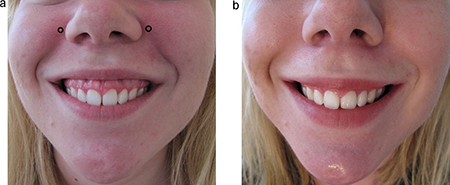

Gingival/”gummy” smile

Target the hyperfunctioning upper lip elevating muscles: levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, levator labii superioris, zygomaticus minor.

Typical dose: 2 to 5 units per side, 2 injections per side, directed into overlapping points of the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi and levator labii superioris and overlapping points of the levator labii superioris and zygomaticus minor,

Chin dimpling

Target the mentalis muscle at the prominence of the chin.

Typical dosage: 5 to 10 units via 1 to 2 injection sites

Horizontal chin crease

Target the mentalis muscle.

Typical dosage: 3 to 5 units on each side of the midline

Avoid injection directly into the crease because this may cause oral incompetence.

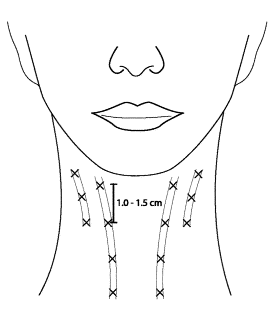

Platysmal bands (Figure 9)

Target each platysmal band.

Typical dosage: 15 units per platysmal band, 3-4 injection sites per band, separated by 1 to 1.5 cm (Brandt)

Do not exceed 30 to 40 units of toxin per treatment to avoid the rare complications neck weakness or dysphagia (Carruthers).

Figure 9. Sample injection pattern for the treatment of platysmal bands, targeting each individual band with 3-4 injections, separated by 1 to 1.5 cm.

Botulinum toxin plus filler

Certain cosmetic indications can best be addressed nonsurgically with a synergistic combination of botulinum toxin injections along with soft tissue fillers (e.g., perioral lines, melomental folds, chin dimpling).

This strategy is most effective when there is some component of static rhytids, due to soft tissue changes or devolumization (as opposed to strictly dynamic rhytids).

Patient management and follow-up

Postoperative instructions, medications prescribed

There are no universally employed postoperative instructions, however some clinicians give patients recommendations that theoretically may minimize the possibility of toxin spread to unwanted areas. These include maintaining an upright position and avoiding exercise or deep massage for several hours following injection.

There are no medications routinely prescribed following treatment.

Other management considerations

As discussed above, the patient’s cosmetic goals and expectations must be thoroughly assessed prior to initiating any type of treatment.

Depending on the patient, achievement of these goals may require a single treatment modality, e.g., botulinum toxin injections alone, or a combination, e.g., botulinum toxin +/- filler injections +/- laser resurfacing +/- surgery.

The physician and patient must both be aware of the advantages, limitations, and potential complications of all these options prior to deciding on a treatment regimen.

Treatment response and follow-up strategies

As previously mentioned, the average duration of effect of any type A toxin is about 3-4 months, when most patients feel as though the effect is wearing off and require additional treatment. The manufacturers of all 3 of the toxins discussed here recommend spacing treatments by at least 3 months.

For a new patient receiving their initial treatment, because the optimal dosing can be somewhat unpredictable, it is preferable to schedule a follow-up appointment in 2–3 weeks, when an assessment can be made regarding efficacy and whether the dose was sufficient to achieve the desired effect.

Some clinicians may give a “booster” injection if the effect is suboptimal, although this should be done with caution because of the rare possibility of immunogenicity. Others advocate waiting until the next treatment session to give an increased dose.

It must be kept in mind that, although there are general dosing recommendations for a given treatment area/indication, patients should not be treated with a “cookbook” approach. Clinicians must be prepared for a trial-and-error period when starting treatment and tailor dosing as needed for each patient.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Local effects at injection site

- Mild swelling, bruising, and discomfort

- These can be minimized by considering temporary discontinuation of anticoagulants, using a small-gauge needle for injection (e.g., 30- or 31-gauge), and holding manual pressure over site following injection.

- Some patients may elect to take certain herbal supplements and bromelain, which may reduce the risk of bruising.

Underdosing

- Not achieving the level of muscle weakening that is desired

- Might not actually be considered a “complication” as it is always better to underdose as opposed to overdose

- Can be easily addressed by reassuring patient and increasing dose at the next treatment

Overdosing

- Leads to undesired excessive muscle weakness

- Specific effects vary depending on injection location.

Effects of toxin migration to adjacent tissues

Specific effects vary depending on injection location and the surrounding musculature and structures. Upper eyelid ptosis may result from medication affects on the levator muscle, which is anticipated to improve 6-8 weeks after treatment.

Immunogenicity/desensitization

Because of the presence of clostridial complexing proteins present in certain formulations (BOTOX® and Dysport®), antibody production is a rare possibility that may reduce efficacy, however, this has been shown to be very rare especially in cosmetic patients (Naumann, Lawrence).

The likelihood of antibody formation is likely related to total protein load; it has been seen in patients receiving very large doses (an overall dose exceeding 300 units) (Klein).

Because Xeomin® is free of complexing proteins, it may be less likely to lead to immunogenicity (Jost, Frevert, 2Dressler).

A potential strategy not clinically proven in cosmetic patients to avoid this rare complication is to minimize the total dose administered and maximize the interval between injections (Mejia).

Prevention

Avoid patients who possess a clear contraindication to treatment.

Approach new patients conservatively with lower doses initially and then titrating upward as needed at later treatments.

Have a solid knowledge of facial anatomy, especially with regard to the musculature involved for a given treatment.

Avoid giving treatments at short intervals or “booster” treatments as these can potentially lead to an immune response to the toxin and desensitization, rendering the toxin less effective.

Managing complications

As the action of the toxin is temporary, management of many complications, mainly those involving overdosing or toxin migration, is generally supportive, e.g., topical lubrication for lagophthalmos or dry eye.

Administration of oral pyridostigmine 60 mg is sometimes used to counter unwanted effects of botulinum toxin injection (Carruthers).

Ophthalmic aproclonidine can be used to treat ptosis secondary to botox treatment. (Scheinfeld N. The use of apraclonidine eyedrops to treat ptosis after the administration of botulinum toxin to the upper face. Dermatol Online J. 2005 Mar 1;11(1):9. PMID: 15748550.)

Controversies

Controversies regarding botulinum toxin in the literature have been discussed in previous sections and include

- Comparison of efficacy and duration among different preparations

- Optimal storage conditions for different preparations

- Actual “shelf life” of toxin after reconstitution

- Optimal dilution parameters

- Concept of immunogenicity of toxin and differences among various preparations

Historical perspective

1895: The bacteria Clostridium botulinum was first discovered by Emile Pierre van Ermengem in Belgium after a botulism outbreak (van Ermengem)

1928: Isolation of crude botulinum toxin type A concentrate by Dr. Herman Sommer and colleagues (Snipe)

1946: Dr. Edward Schantz isolates a purified type A botulinum toxin in crystalline form for use in humans (Schantz)

1960s: Dr. Alan Scott begins researching the use of botulinum toxin to treat strabismus in monkeys. (Scott)

1989: OnabotulinumtoxinA gets FDA approval for the treatment of blepharospasm and strabismus

1992: Cosmetic use for the improvement of facial rhytids (specifically, glabellar lines) first described in the literature. Off-label aesthetic use is practiced for many years. (5Carruthers)

2002: OnabotulinumtoxinA FDA-approved for the treatment of glabellar furrows

2009: AbobotulinumtoxinA FDA-approved for the treatment of glabellar furrows

2011: IncobotulinumtoxinA FDA-approved for the treatment of glabellar furrows

2013: OnabotulinumtoxinA FDA-approved for the treatment of lateral canthal lines (crow’s feet)

References and additional resources

- AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System, 2013-2014.

- AAO, Focal Points: Facial Fillers, Botulinum Toxin, and Facial Rejuvenation, Volume XXIX, Number 4, Module 1 of 3, 2011.

- AAO Monograph 8, Surgery of the Eyelids, Lacrimal System, & Orbit, 2nd edition, 2011.

- Aoki KR, Guyer B. Botulinum toxin type A and other botulinum toxin serotypes: a comparative review of biochemical and pharmacological actions. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:21–29.

- Bakshi E, Hartstein ME. Compositional differences among commercially available botulinum toxin type A. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011 Sep;22(5):407-12.

- Barinaga M. Secrets of secretion revealed. Science. 1993;260:487–489.

- Bistoni G and Figus A. “Botulinum Toxin Type a Treatment in Facial Rejuvenation.” Minimally Invasive Procedures for Facial Rejuvenation. Eds. Curinga Giuseppe and Rusciani Antonio. Foster City, CA: OMICS Group eBooks, 2014. 1-42. OMICS Group International – eBooks. June 2014.

- Blasi J, Chapman ER, Link E, et al. Botulinum neurotoxin A selectively cleaves the synaptic protein SNAP-25. Nature. 1993;365:160–163.

- Bonaparte JP, Ellis D, Quinn JG, et al. A comparative assessment of three formulations of botulinum toxin A for facial rhytides: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Syst Rev. 2013 Jun 13;2:40.

- Brandt FS, Boker A. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of neck lines and neck bands. Dermatol Clin. 2004 Apr;22(2):159-66.

- Brin MF, Comella CL, Jankovic J, et al. CD-017 BoNTA Study Group. Long-term treatment with botulinum toxin type A in cervical dystonia has low immunogenicity AQ3 by mouse protection assay. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1353–1360.

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J. Botulinum toxin type A: history and current cosmetic use in the upper face. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2001;20:71.

- Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Cohen J. A prospective, double-blind, randomized, parallel- group, dose-ranging study of botulinum toxin type a in female subjects with horizontal forehead rhytides. Dermatol Surg. 2003 May;29(5):461-7.

- Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Aesthetic botulinum A toxin in the mid and lower face and neck. Dermatol Surg. 2003 May;29(5):468-76.

- Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Botulinum toxin (botox) chemodenervation for facial rejuvenation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2001;9:197–204.

- Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Practical cosmetic Botox techniques. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999 Dec;3 Suppl 4:S49-52.

- Carruthers JD, Carruthers JA. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992 Jan;18(1):17-21.

- Carruthers JD, Glogau RG, Blitzer A. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type a, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies–consensus recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 May;121(5 Suppl):5S-30S; quiz 31S-36S.

- Chen F, Kuziemko GM, Stevens RC. Biophysical characterization of the stability of the 150-kilodalton botulinum toxin, the nontoxic component, and the 900-kilodalton botulinum toxin complex species. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2420–2425.

- Coffield JA, Bakry N, Zhang RD, et al. In vitro characterization of Botulinum toxin types A, C and D action on human tissues: combined electrophysiologic, pharmaco-logic and molecular biologic approaches. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:1489–1498.

- DailyMed – DAXXIFY- botulinum toxin type a injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution. Accessed March 23, 2023. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=3aaa6e14-a3f7-4fb2-b9f9-d3a9c3ae1f74

- de Maio M and Rzany B eds. Botulinum Toxin in Aesthetic Medicine. Heidelberg: Springer, 2007. Print.

- Dorizas A, Krueger N, Sadick NS. Aesthetic uses of the botulinum toxin. Dermatol Clin. 2014 Jan;32(1):23-36.

- Dressler D. Botulinum toxin therapy failure: causes, evaluation procedures and management strategies. Eur J Neurol. 1997;4:(suppl. 2):S67–S70.

- Dressler D. Five-year experience with incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin]): the first botulinum toxin drug free of complexing proteins. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:385–389.

- Fagien S. Botox for the treatment of dynamic and hyperkinetic facial lines and furrows: adjunctive use in facial aesthetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:701–713.

- Fagien S, Brandt FS. Primary and adjunctive use of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) in facial aesthetic surgery: beyond the glabella. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:127–148.

- Frankel AS. Botox for rejuvenation of the periorbital region. Facial Plast Surg. 1999;15:255–262.

- Frevert J. Xeomin is free from complexing proteins. Toxicon. 2009;54:697–701.

- Giacometti J, Yen MT. Re: “Comparison of preferences between onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) and incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin) in the treatment of benign essential blepharospasm”. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Jan-Feb;30(1):76-7.

- Giacometti JN, Yen MT. Update on botulinum toxins in oculofacial plastic surgery. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2013 Summer;53(3):21-31.

- Hambleton P. Clostridium botulinum toxins: a general review of involvement in disease, structure, mode of action and preparation for clinical use. J Neurol. 1992;239:16–20.

- Hexsel DM, De Almeida AT, Rutowitsch M, et al. Multicenter, double-blind study of the efficacy of injections with botulinum toxin type A reconstituted up to six consecutive weeks before application. Dermatol Surg. 2003 May;29(5):523-9; discussion 529.

- Higgins S, Wysong A. Cosmetic Surgery and Body Dysmorphic Disorder – An Update. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;4(1):43-48. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.09.007

- Hui JI, Lee WW. Efficacy of fresh versus refrigerated botulinum toxin in the treatment of lateral periorbital rhytids. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Nov-Dec;23(6):433-8

- Inoue K, Fujinaga Y, Watanabe T, et al. Molecular composition of Clostridium botulinum type A progenitor toxins. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1589–1594.

- Jaspers GW, Pijpe J, Jansma J. The use of botulinum toxin type A in cosmetic facial procedures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011 Feb;40(2):127-33.

- Jost WH, Blümel J, Grafe S. Botulinum neurotoxin type A free of complexing proteins (XEOMIN) in focal dystonia. Drugs. 2007;67(5):669-83.

- Klein AW. Contraindications and complications with the use of botulinum toxin. Clin Dermatol. 2004 Jan-Feb;22(1):66-75.

- Lawrence I, Moy R. An evaluation of neutralizing antibody induction during treatment of glabellar lines with a new US formulation of botulinum neurotoxin type A. Aesthet Surg J. 2009 Nov;29(6 Suppl):S66-71.

- Lizarralde M, Gutiérrez SH, Venegas A. Clinical efficacy of botulinum toxin type A reconstituted and refrigerated 1 week before its application in external canthus dynamic lines. Dermatol Surg. 2007 Nov;33(11):1328-33; discussion 1333.

- Long-lasting Frown Line Treatment – DAXXIFY®. Long-lasting Frown Line Treatment – DAXXIFY®. Accessed March 27, 2023. https://daxxify.com

- Mejia NI, Vuong KD, Jankovic J. Long-term botulinum toxin efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity. Mov Disord. 2005 May;20(5):592-7.

- Naumann M, Carruthers A, Carruthers J, et al. Meta-analysis of neutralizing antibody conversion with onabotulinumtoxinA (BOTOX®) across multiple indications. Mov Disord. 2010 Oct 15;25(13):2211-8.

- Niemann H. Molecular biology of clostridial neurotoxins. In: Alouf JH, Freer JH, eds. A Sourcebook of Bacterial Protein Toxins. London: Academic Press; 1991: 303–348.

- Ohishi I, Sugii S, Sakaguchi G. Oral toxicities of Clostridium botulinum toxins in response to molecular size. Infect Immun. 1977;16:107–109.

- Prager W, Wissmüller E, Kollhorst B, Williams S, Zschocke I. Comparison of two botulinum toxin type A preparations for treating crow’s feet: a split-face, double-blind, proof-of-concept study. Dermatol Surg. 2010 Dec;36 Suppl 4:2155-60.

- Ranoux D, Gury C, Fondarai J, et al. Respective potencies of Botox and Dysport: a double blind, randomised, crossover study in cervical dystonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002 Apr;72(4):459-62.

- Sattler G, Callander MJ, Grablowitz D, et al. Noninferiority of incobotulinumtoxinA, free from complexing proteins, compared with another botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar frown lines. Dermatol Surg. 2010 Dec;36 Suppl 4:2146-54

- Schantz EJ, Johnson EA. Botulinum toxin: the story of its development for the treatment of human disease. Perspect Biol Med 1997;40(3):317–27.

- Schiavo G, Benfenati F, Poulain B, et al. Tetanus and botulinum toxin-B neurotoxins block neurotransmitter release by proteolytic cleavage of synaptobrevin. Nature. 1992;359:832–835.

- Scott AB. Botulinum toxin injection into extraocular muscles as an alternative to strabismus surgery. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1980;17:21–25.

- Scott AB. Botulinum toxin injection of eye muscles to correct strabismus. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;79:734–770.

- Semchyshyn N, Sengelmann RD. Botulinum toxin A treatment of perioral rhytides. Dermatol Surg. 2003 May;29(5):490-5; discussion 495.

- Shone CC. Clostridium botulinum neurotoxins, their structures and modes of action. In: Watson, ed. Natural Toxicants in Foods. Chichester: Ellis Harwood Ltd.; 1986: 11–57.

- Simonetta Moreau M, Cauhepe C, et al. A double-blind, randomized, comparative study of Dysport vs. Botox in primary palmar hyperhidrosis. Br J Dermatol. 2003 Nov;149(5):1041-5.

- Snipe PT, Sommer H. Studies on botulinus toxin. 3. Acid preparation of botulinus toxin. J Infect Dis 1928;43:152–60.

- Sollner T, Rothman JE. Neurotransmission: harnessing fusion machinery at the synapse. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:344–348.

- van Ermengem E. Classics in infectious diseases. A new anaerobic bacilus and its relation to botulism. Rev Infect Dis 1979;1(4):701–19. (Originaly published as ‘Ueber einen neuen anaeroben Bacilus und seine Beziehungen zum Botulismus’ in Zeitschrift fur Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten 1897;26:1–56.)

- Walker TJ, Dayan SH. Comparison and overview of currently available neurotoxins. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014 Feb;7(2):31-9.

Financial disclosures

Reviewers

Viraj Mehta – No disclosures