Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid, Drug-Induced Pemphigoid, and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP)

- Chronic bilateral cicatrizing conjunctivitis with autoimmune etiology

- Also known as mucous membrane pemphigoid when affecting nonocular surfaces (oral, oropharynx, larynx, skin, genitalia, anus)

- Type II hypersensitivity reaction with deposition of immunoglobulins along the epithelial basement membrane zone

- Autoantibodies to basement membrane zone initiate the compliment cascade.

- Leukocytes, mast cells, and macrophages are then recruited and a series of cytokines are released, resulting in formation of subepithelial bullae.

- Fibroblast activation leads to scarring.

Drug-induced pemphigoid

- Also known as pseudopemphigoid

- Clinical picture similar to OCP, but without systemic involvement

- Associated with chronic use of topical ophthalmic medications, especially glaucoma medications

- Pilocarpine

- Timolol

- Idoxuridine

- Dipivefrin

- Echothiophate iodide

- Demecarium bromide

- Might represent sensitization of a patient already predisposed to OCP

- Disease process does not progress once the offending agent has been discontinued.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)

- Systemic mucocutaneous reaction, which results in bullae, sloughing, and scarring of epidermis and mucous membranes

- Type III hypersensitivity reaction in which immune complexes are deposited in the dermis and conjunctival stroma

- It can occur as a result of exposure to

- Medications

- Allopurinol

- Antibiotics (sulfonamides, penicillin, ampicillin, isoniazid)

- Antiepileptics (lamotrigine, phenytoin, carbamazepine)

- NSAIDS (meloxicam, piroxicam)

- Antiretroviral (nevirapine)

- Cases of SJS related to many other medications have been reported.

- Infection

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Herpes simplex virus

- Streptococci

- Adenovirus

Epidemiology

OCP

- Reported incidence 1 in 12,000 to 1 in 60,000 people per year

- Average age of presentation is 65 years, although patients often present late in the disease. Rarely occurs below age 30.

- Average duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis is 2.8 years.

- More common in females than males by 2:1 ratio

SJS

- Reported incidence 2–5 cases per million people per year

- More common in females than males

- More common in children and young adults

- Increased incidence in patients with AIDS

History

OCP and drug-induced pemphigoid

- History of chronic red, irritated eye

- History of nonocular mucosal or cutaneous lesions (OCP)

- History of exposure to topical agents that can incite drug-induced pemphigoid — see list of medications above.

SJS

- History of exposure to inciting factors

- New medication or dose change

- Recent symptoms of upper respiratory infection

- See list of inciting factors above.

- Timing of symptom onset

- Stability or progression of symptoms

Clinical features

OCP and drug-induced pemphigoid

- Ocular findings

- Conjunctival hyperemia, edema, ulceration

- Aqueous and mucous tear dysfunction

- Subepithelial bullae

- Subepithelial fibrosis (Stage I)

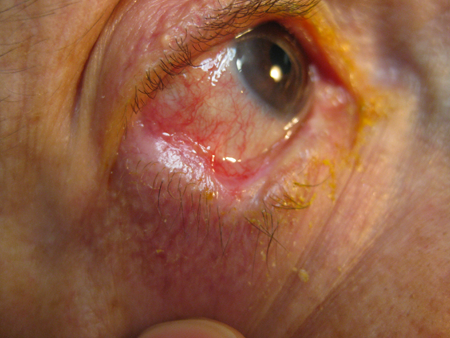

- Shortening of fornices (Stage II) (Figure 1)

- Symblepharon (Stage III)

- Extensive adhesions between the lid and the globe (Stage IV)

- Cicatricial entropion and trichiasis can develop with extensive scarring.

- Secondary corneal abrasions, vascularization and scarring as well as keratinization of the ocular surface

- Nonocular findings

- Dysphagia requires urgent evaluation because esophageal scarring and strictures can lead to aspiration.

- Desquamative gingivitis

- Hoarseness or dysphonia secondary to laryngeal or epiglottis lesions

- Cutaneous vesicula-bullous lesions or erythematous plaques

SJS

- Fever, arthralgias, or generalized malaise might precede ocular or cutaneous symptoms

- Cutaneous findings

- Target lesion

- Maculopapular or bullous skin lesions

- Epithelial sloughing

- Mucous membrane involvement

- Oral hemorrhagic erosions

- Genital lesions

- Pharyngeal lesions can lead to airway compromise.

- Ocular findings

- Conjunctival hyperemia, edema, subepithelial bullae, sloughing and/or necrosis (Figure 2)

- Corneal ulcerations

- Symblepharon or conjunctival scarring

Figure 1. Patient with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Note presence of symblepharon and shortening of inferior fornix.

Figure 2. Patient with SJS demonstrating fluorescein staining of bulbar, palpebral conjunctiva, and eyelid margins.

Testing

OCP

Perform a complete ophthalmic examination with careful examination of conjunctiva, cornea, fornices, and eyelids.

Evaluate forniceal depth.

Take photos to document the involved areas.

The gold standard for diagnosis is conjunctival biopsy with immunofluorescence or immunoperoxidase staining.

- Take a sample from an area abutting inflamed and noninflamed conjunctiva.

- Take a fresh sample for immediate staining or storage in Zeus or Michel’s media.

- Immunostaining demonstrates linear deposition of immunoreactants along the basement membrane zone.

- False negatives are not uncommon, and a negative biopsy does not rule out OCP.

- If clinical suspicion is high, consider a repeat biopsy.

A multidisciplinary approach is usually required for evaluation and management of airway, cutaneous, oropharyngeal, and ophthalmic manifestations.

SJS

A multidisciplinary approach is usually required for evaluation and management of airway, cutaneous, genital, and ophthalmic manifestations.

In-patient care is usually indicated in the acute phase and admission to a burn unit should be considered in severe cases.

Perform a complete ophthalmic exam with careful attention to conjunctiva, cornea, and eyelid margins.

Note location and size of areas of corneal, conjunctival, and eyelid margin fluorescein staining.

Evaluate fornices and evert upper eyelid to allow for evaluation of the upper palpebral conjunctiva.

Take photos to document the involved areas.

During acute phase, re-evaluate patients daily until it is clear that the disease process is stable or improving.

Risk factors

OCP

- Age (usually > 60)

- Sex (F > M)

- Genetic predisposition

- HLA-DR4 and DQw3 have been associated with increased incidence of OCP.

Drug-induced pemphigoid

- Use of topical ophthalmic medications

SJS

- HIV

- Infectious agents

- Medications

- Genetic predisposition

- Multiple HLA haplotypes have been associated with sulfonamide, carbamazepine, and allopurinol-associated SJS.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for cicatricial conjunctivitis as seen in OCP and SJS is broad and includes both infectious and immune mediated etiologies.

Infectious

- Trachoma

- Adenovirus keratoconjunctivitis

Immune mediated

- OCP

- Drug-induced pemphigoid

- SJS

- Atopic keratoconjunctivitis

- Sarcoidosis

- Ocular rosacea

- Lupus erythematosus

- Lichen planus

Other

- Chemical burn

- Trauma

- Radiation

- Neoplasm

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

OCP

- OCP is a slowly progressive disease.

- Early in the course of the disease, patients have recurrent or chronic papillary conjunctivitis, usually bilateral.

- Chronic ocular surface inflammation and irritation leads to conjunctival fibrosis and scarring.

- Recurrent inflammation leads to destruction of goblet cells and meibomian glands, as well as obstruction of lacrimal gland ductules. This causes a global (aqueous, lipid, and mucous) tear dysfunction.

- Conjunctival scarring leads to forniceal shortening, symblepharon, cicatricial entropion, and trichiasis.

- Tear dysfunction, lid dysfunction, and persistent inflammation can lead to corneal vascularization, scarring, infection, ulceration, perforation, and potentially blindness.

- Outcome and prognosis depend on the region(s) affected, severity, and time to initiation of treatment.

Drug-induced pemphigoid

- Left untreated, drug-induced pemphigoid can progress similarly to OCP.

- Progression usually ceases once offending agent is discontinued.

SJS

- Prodrome of malaise, fever, arthralgias is followed by skin lesions developing within a few days.

- Mucous membrane and ocular involvement can precede or follow cutaneous changes.

- The acute phase usually lasts 1–2 weeks, followed by a prolonged period of re-epithelialization.

- Inflammation can lead to destruction of goblet cells, meibomian glands, and limbal stem cells.

- Conjunctival scarring can lead to forniceal shortening, symblepharon, cicatricial entropion, and trichiasis.

- Tear dysfunction, lid dysfunction, and persistent inflammation can lead to corneal vascularization, scarring, infection, ulceration, perforation, and potentially blindness.

- Although most patients have only a single course of SJS, recurrence has been reported.

- Outcome and prognosis depend on the region(s) affected and severity.

Medical therapy

OCP and drug-induced pemphigoid

- Ocular surface disease should be managed with aggressive lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears and ointments.

- Topical cyclosporine ophthalmic drops can also be useful for local control, though it will neither prevent nor treat systemic manifestations of MMP.

- Consultation with physician familiar with the use of immunomodulating and cytotoxic agents is recommended when starting medical therapy for OCP.

- Slowly progressive and mild disease can be treated with dapsone.

- Rule out G6PD deficiency prior to initiating therapy.

- Moderate disease or patients who failed therapy with dapsone can be treated with mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept) or methotrexate.

- Treat patients with rapidly progressive disease or severe inflammation with high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan).

- Other therapeutic options:

- TNF-alpha inhibitors

- Rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin

Drug-induced pemphigoid

- Cessation of offending agent

- Further management similar to OCP

SJS

- Systemic therapy

- Care is mostly supportive, and use of systemic corticosteroids is controversial.

- Ocular therapy

- Medical therapy focuses mainly on ocular surface lubrication with preservative-free artificial tear drops or gels.

- Topical steroids with coadministration of prophylactic topical antibiotics can be helpful.

- The authors’ institution advocates for coadministration of preservative-free artificial tears qid, dexamethasone ophthalmic 0.1% qid, moxifloxacin 0.5% qid, and cyclosporine ophthalmic 0.05% bid with staggered dosing, such that the patient receives at least 1 drop every 2 hours.

Surgery

OCP and drug-induced pemphigoid

- Surgical correction of cicatricial eyelid deformities or trichiasis can be required to achieve a stable ocular surface.

- Manipulation of the ocular surface can promote cicatrization, so delay surgical management until disease activity has been under control for an extended period.

SJS

- Amniotic membrane transplantation to cover the entire ocular surface, including the lid margins and cornea, in cases with moderate to severe ocular involvement in the acute phase

- Early treatment leads to better visual outcomes and fewer long-term complications.

- ProKera or sutured amniotic membrane graft can be used to cover cornea, depending on degree of corneal involvement.

- Concurrent lysis of symblepharon if present

- Amniotic membrane grafts should be left in place for 10–14 days or until the graft begins to break down.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Standard surgical risks

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Recurrence

- Progression of disease despite surgical intervention

- Need for further procedures in the future

- Globe perforation

- Vision loss

Complications of immunomodulating therapy

Dapsone

- Hemolytic anemia secondary to G6PD deficiency

- Agranulocytosis

- Aplastic anemia

- Nausea

- Abdominal pain

- Hepatitis

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Monitoring: G6PD levels (prior to starting medication), CBC, LFTs

Mycophenolate mofetil

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Stomach pain

- Fever

- Anemia

- Monitoring: CBC and LFTs

Methotrexate

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Hair thinning

- Transaminitis

- Monitoring: CBC and LFTs

Cyclophosphamide

- Leucopenia, anemia, alopecia, infertility, hemorrhagic cystitis, bone marrow suppression, bladder carcinoma, and other malignancies

- Monitoring: CBC, renal function, LFTs, urinalysis

Disease-related complications

- Chronic ocular surface inflammation

- Dry eye

- Conjunctival scarring and keratinization

- Fornix shortening

- Symblepharon

- Cicatricial entropion

- Trichiasis/distichiasis

- Limbal stem cell deficiency

- Corneal vascularization, ulceration, opacification

- Vision loss

Medical management

Aggressive lubrication with artificial tears, ointments, and gels is the mainstay of treatment for ocular surface disease.

Therapeutic contact lenses can be considered for patients with severe surface disease.

Efficacy of autologous serum tears, topical steroids, and topical cyclosporine has also been reported.

Surgical management

- Punctal occlusion (with punctual plugs or punctual cautery) can be considered if patient has patent nasolacrimal system.

- Eyelid reconstruction for cicatricial entropion

- Lid reconstruction should be performed prior to surgical management of the ocular surface.

- Hard palate and/or buccal mucosal grafting might be required for fornix reconstruction.

- Laser ablation of lashes for trichiasis/distichiasis

- Limbal stem cell transplant can be considered for severe ocular surface failure.

- Penetrating keratoplasty has poor prognosis in patients with SJS and OCP secondary to irregular surface and abnormal tear film.

- However, it can be considered in patients with corneal thinning or perforation.

- Keratoprosthesis has been used with some success.

Patient instructions

OCP and drug-induced pemphigoid

- Patients should be educated on the severity of the disease, the potential systemic manifestations, and the need for a multidisciplinary approach.

- Patients should be instructed to use frequent artificial tear drops and gels.

- The potential side effects of immunomodulating therapy and the need for long-term therapy, monitoring, and close follow-up should also be discussed.

- Postsurgical patients will have similar instructions, as well as routine postoperative instructions (combination drops, pain medications, etc.).

Drug-induced pemphigoid

- Patients should be counseled regarding the offending agent as well as other topical medications that can exacerbate OCP.

- Further counseling similar to OCP depending on severity of disease

SJS

- Patients should be educated on the severity of the disease and the need for in-patient care in the acute phase.

- Patients should be instructed to use frequent artificial tear drops and gels once out of the acute phase, and educated on the potential complications of the disease.

- They should be instructed to keep regular follow-up visits based on severity of disease.

- Postsurgical patients will have similar instructions as well as routine postoperative instructions (combination drops, pain medications, etc.).

References and additional resources

- AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 8: External Disease and Cornea, 2010-11.

- Butt Z, Kaufman D, McNab A, McKelvie P. Drug-induced ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: a series of clinico-pathological reports. Eye (Lond). 1998;12(Pt 2):285-290.

- Ciralsky JB, Sippel KC, Gregory DG. Current ophthalmologic treatment strategies for acute and chronic Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(4):321-328.

- Gregory DG. The ophthalmologic management of acute Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2008;6(2):87-95

- Kheirkhah A, Blanco G, Casas V Surgical strategies for fornix reconstruction based on symblepharon severit Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 Aug;146(2):266-275.

- Kirzhner M, Jakobiec Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: a review of clinical features, immunopathology, differential diagnosis, and current management. Semin Ophthalmol. 2011;26(4-5):270-277.

- Mortensen XM, Shenkute NT, Zhang AY, Banna H. Clinical Outcome of Amniotic Membrane Transplant in Ocular Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis at a Major Burn Unit. Am J Ophthalmol. 2023 Dec;256:80-89. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2023.07.026. Epub 2023 Aug 19. PMID: 37598739.

- Nirken MH, High WA, Roujeau JC. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. www.uptodate.com.

- Rojas, John K G Dart, and Valerie P J Saw. The natural history of Stevens–Johnson syndrome: patterns of chronic ocular disease and the role of systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. Aug 2007; 91(8): 1048-1053.