Congenital Lacrimal Dysgenesis

Updated July 2024

Embryology of lacrimal drainage system

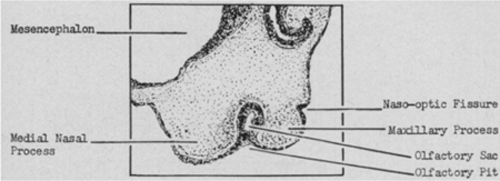

The anlage of the membranous lacrimal conduit begins as an ectodermal thickening along the naso-optic fissure in the 7-mm or 32-day embryo (Figure 1).

This thickened ectoderm lies between the lateral nasal and maxillary processes and arises at about the same time as the olfactory groove.

The olfactory pit is well formed in the 9-mm or 37-day embryo and the thickened ectoderm of the lacrimal anlage detaches and becomes buried beneath the surface ectoderm in the 12-mm or 42-day embryo.

The solid cord of epithelial cells becomes canalized beginning in the 32–36-mm or 60-day embryo, first patent at the ocular end and concluding at the lower nasal end.

Figure 1. (AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1952;47(2):141–158).

The horizontal portion of the lacrimal system establishes a lumen before the vertical portion and connects with the canaliculi forming at the lid margin.

Distal canalization at the inferior meatus occurs after birth.

- In a 1950 study at the Carnegie Institute of Washington, the nasolacrimal passages of 15 full-term stillborn infants were examined.

- The nasolacrimal duct was found to be in communication with the nose at birth in only 27% of cases.

- 2 infants had 1 duct open and the other closed.

- Only 2 infants had both ducts open to the nose.

- Only a mucosal membrane separated the lacrimal duct from the nasal meatus, and the distal duct was ballooned under the inferior turbinate.

Spectrum of congenital dysgenesis

Atresia of the lacrimal puncta or canaliculi:

- May range from complete atresia of the puncta and canaliculi to a thin membrane overlying the punctum with a normal canaliculus beneath

- May be associated with craniofacial syndromes

Congenital lacrimal fistula: an epithelialized tract extending from the common canaliculus or lacrimal sac to the skin surface, normally just inferonasal to the medial canthus

- Prevalence reported 1 in 2000 live births (Chaung, Orbit 2016)

- Frequently unilateral, although familial cases bilateral

- Lacrimal and systemic anomalies additionally associated

Dacryocystocele (see dacryocystocele topic)

Dacryostenosis

- Most common cause is the failure of canalization of the duct at its mucosal entrance beneath the inferior meatus at the valve of Hasner.

- Deviated septum and impaction of the inferior turbinate on the membranous portion of the duct may contribute.

- Osseous stenosis and obstruction of the NLD have been reported.

Epidemiology and associated conditions

Up to 6% of newborns have congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

- Symptoms become manifest in 80%–90% by 1 month of age.

- Approximately 1/3 are bilateral.

- Approximately 90% of congenital NLD resolve by 1 year.

Double Punctal Anomalies

- Medial punctum typically abnormal with a lac of a vertical canalicular component

- Dacryocystography and canalicular endoscopy highlight different accessory canaliculi length (Timlin, OPRD 2019)

In a study of 50 patients with lacrimal dysgenesis in Australia managed between 1992 and 2003, 40% had a systemic syndrome or dysmorphism (Ophthalmology 111:1782, 2004).

- Ectodermal dysplasia was associated with meibomian gland hypoplasia.

- Hay Wells syndrome was associated with ankyloblepharon and medial lid hypoplasia.

- Nager syndrome was associated with a bifid caruncle.

In a study of 7 patients with single wall canalicular dysgenesis in India, there were no specific systemic associations (OPRS 29:464, 2013).

History and physical exam

Tearing since birth or shortly thereafter:

- Tearing with minimal mucopurulent discharge may indicate punctal or canalicular agenesis.

- Tearing with mucopurulent discharge suggests NLD obstruction.

- Intermittent tearing with mucopurulent discharge is suggestive of intermittent NLD obstruction due to swelling of the inferior turbinate’s mucosa associated with upper respiratory tract infection or allergies.

Steven-Johnson syndrome, herpes simplex, and varicella have been reported to lead to punctual and canalicular scarring.

Associated craniofacial anomalies or clefting syndromes suggest significant disruption of the lacrimal drainage system:

- Cleft palate, Goldenhar syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, Treacher-Collins syndrome, hemifacial microsomia, and trisomy 21 have all been associated with nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

Lid malpositions — entropion, epiblepharon, trichiasis — may cause reflex tearing.

Enlarged cornea and thinned sclera suggest congenital glaucoma.

Test to diagnosis infant

Dye disappearance test:

- Place fluorescein in the inferior fornix.

- Wipe away excess.

- Examine at 5 minutes.

- Presence of dye suggests nasolacrimal outflow impedance.

Dye may highlight a lacrimal fistula.

Management, treatment, and follow-up

Observation

In approximately 90% of patients, congenital dacryostenosis resolves spontaneously by 13 months as the nasal cavity and space beneath the inferior turbinate enlarge.

Conservative management

- Massage of the lacrimal sac via the Crigler method

- Topical antibiotic ointment or drops for discharge or crusting

Surgical options

- Probing and irrigation of the nasolacrimal duct

- May be performed in the office to avoid the risk of general anesthesia

- Advantages of performing in the operating room under mask or general anesthesia include increased control, ability to infracture the inferior turbinate, resect nasal cysts if appropriate

- Inferior turbinate infracture is of benefit if epiphora is associated with nasal congestion

- Timing of probing and irrigation and success rates

- Most authors recommend probing and irrigation by 12 to 13 months of age if child still symptomatic

- Success rates exceed 90% in most studies in patients < 15 months

- Conflicting data regarding the efficacy of probe and irrigation after 36 months

- Trephine and silicone intubation may be needed

- If initial probing and irrigation fails, it may be combined with balloon dacryoplasty

- If a lacrimal fistula is present, this may require excision of the fistula and closure with successful treatment in 82% of cases (Al-Salem, Br J Ophthal 2014)

- Dacryocystorhinostomy is rarely needed

- Conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy is indicated when upper tear drain pathology prohibits reconstruction

References and additional resources

- AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 6: Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System, 2013-2014.

- AAO, Surgery of the Eyelid, Orbit & Lacrimal System, Vol. 1, 1993, p. 102-103.

- AAO, Surgery of the Eyelid, Orbit & lacrimal System, Vol. 3, 1995, p. 265-268, 286.

- Al-Salem K, Gibson A, Dolman PJ. Management of congenital lacrimal (anlage) fistula. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014 Oct;98(10):1435-6.

- Chaung JQ, Sundar G, Ali MJ. Congenital lacrimal fistula: A major review. Orbit. 2016 Aug;35(4):212-20.

- Choi YM, Jang Y, Kim N, Choung HK, Khwarg SI. The effect of lacrimal drainage abnormality on the surgical outcomes of congenital lacrimal fistula and vice versa. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2022 Jan;32(1):108-114.

- Weiss AH, Baran F, Kelly J. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: delineation of anatomic abnormalities with 3-dimensional reconstruction. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(7):842-8.

- Heyman S, Katowitz JA, Smoger Dacryoscintigraphy in children. Ophthalmic Surg. 1985;16(11):703-9.

- Timlin HM, Keane PA, Ezra DG. Characterizing Congenital Double Punctum Anomalies: Clinical, Endoscopic, and Imaging Findings. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Nov/Dec;35(6):549-552.