Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction (NLDO)

Updated July 2024

Michael A. Kipp, MD; Richard C. Allen, MD, PhD

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Most common is membranous obstruction at valve of Hasner in distal nasolacrimal duct (NLD)

- Narrowing of proximal NLD

- Occlusion or absence of punctum

- Malformation of the lacrimal duct opening

- Canalicular obstruction

- Congenital

- After HSV or EKC infection

- Traumatic

- Jones and Wobig had also described seven other anatomical variations causing obstruction of the lower nasolacrimal duct system including: the duct extends to the floor of the nose lateral to the nasal mucosa; the duct extends several millimeters down lateral to the nasal mucosa without an opening; the duct fails to canalize due to failure of osseous nasolacrimal canal formation; an impacted inferior turbinate blocks the duct meatus; the ducts ends blindly in the anterior end of the inferior turbinate; the duct ends blindly in the medial wall of the maxillary sinus; and a bony nasolacrimal duct extends to the floor of the nose without an opening.

Epidemiology

- 50% of newborns have valve of Hasner obstruction

- 5–15% of infants have clinical NLDO

- Recent study of children born in Olmsted County, MN, revealed a prevalence of one in nine live births (Sathiamoorthi et al., 2018)

- One-third of cases bilateral

- Males and females equally affected

- Associated with premature birth

- More prevalent among Caucasians

History

- Tearing and discharge, commonly presenting within first month of life

- Discharge accumulates with sleep

- Symptoms worse with URI or outside in cold, windy weather

- Tearing with mucopurulent discharge usually indicates distal obstruction; tearing without discharge usually indicates proximal ductal stenosis.

- Question caretaker about conjunctival injection, photophobia, blepharospasms, history of allergy/atopy.

- Other pertinent questions: Daily or intermittent symptoms? Improving or worsening during first year?

- Less common presentations

- Onset after first year of life

- After HSV or EKC infection

- Dacryocystocele

- Due to trauma of the nasolacrimal system

Clinical features

- Excess tear film and mucous discharge

- Quiet eyelids and conjunctiva indicating no infectious etiology, especially important in first week of life

- Reflux from NL sac with digital pressure

- Evaluate for trichiasis, epiblepharon.

- Evaluate for signs of glaucoma.

- Look for open punctum on each eyelid (portable slit lamp or 20 D lens).

Dye disappearance testing (Figure 1) is helpful to confirm the diagnosis, but a crying infant can confound results. On testing, when fluorescein is visible in the nostril and patient is still symptomatic this might suggest NLD stenosis severe enough to cause symptoms; however, an alternative diagnosis should be sought.

Less common findings:

- Duplicate puncta

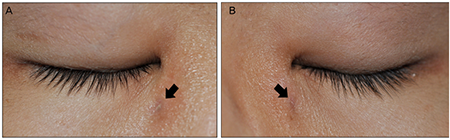

- NLD system fistula: Can be patent (Figure 2)

- Dacryocystocele/dacryocystitis:

- Accumulation of mucous in NL sac from distal valve of Hasner obstruction and unusually competent proximal valve of Rosenmuller

- Blue discoloration in medial canthus region, inferior to medial canthal tendon (Figure 3), often is seen at birth and is usually due to amniotic fluid accumulation (amniotocele).

- Female incidence twice as high as male

- Infectious dacryocystitis possible consequence — about 50% on presentation

- Question caretakers about difficulty feeding.

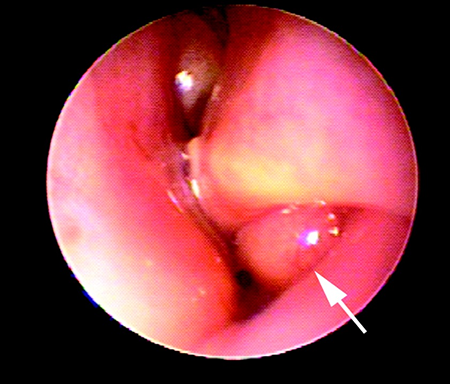

- Can be associated intranasal cysts — about 25% (Figure 4)

- Can be bilateral > 25% of cases

- More urgent evaluation and treatment needed

Figure 1. Primary dye disappearance test on right-sided NLDO. (Courtesy Oculoplastic Surgery Unit, Fuenlabraden Hospital, Madrid).

Figure 2. Nasolacrimal fistula. (Courtesy Journal of Korean Ophthalmologic Society 2013;54:11).

Figure 3. Right congenital dacryocystocele (EyeRounds Online Atlas of Ophthalmology) and left congenital dacryocystocele with dacryocystitis.

Figure 4. Nasal cyst associated with dacryocystocele. Open Journal of Pediatrics 2012:2(2).

Risk factors

- Down syndrome:

- 22% NLDO incidence

- Narrower transverse diameter of NLD

- Higher incidence of nasal mucosa inflammation

- Higher incidence of other abnormalities

- Anlage NL sac fistula

- Double punctum

- Craniofacial syndromes: Crouzon, Aperts, Treacher-Collins, Centurion

- Premature birth

- Goldenhar syndrome

- Clefting syndromes

- Possible genetic predisposition to basic NLDO

Differential diagnosis

NLDO symptoms

- Epiblepharon/trichiasis

- Lashes contacting not only conjunctiva, but cornea

- SPK present (seen with fluorescein staining or through retinoscopic reflex)

- Dye disappearance can prove helpful here.

- Use of lubricants in first year of life and wait for spontaneous improvement of epiblepharon

- If epiblepharon needs repair after first year, NLD patency can be checked under anesthesia simultaneously.

- Congenital glaucoma

- Photophobia/blepharospasm common

- Buphthalmos, myopia, optic nerve cupping

- Check IOP in office if questionable.

- Icare tonometer (Icare Finland Oy, Helinski, Finland) usually easier

- Feeding child can be helpful

- Infectious conjunctivitis/ophthalmia neonatorum

- Consider infectious etiology first 1–2 weeks of life

- Conjunctival injection, purulent discharge

- Maternal history venereal diseases

- Look for corneal involvement

- Culture for gonococcus, chlamydia, HSV as needed

- Allergy

- Can be primary cause or contributing factor of tearing and discharge

- History of frequent rhinitis, sinusitis, eczema

- Itching, conjunctival injection

- Usually later-onset presentation

- Consider anti-allergy topical drops, nasal sprays or systemic medications if suspect

Dacryocystocele

- Meningoencephalocele

- Swelling above medial canthal tendon

- Pulsation common

- Hemangioma

- Reddish-purple discoloration

- Look for additional skin lesions

- Dermoid cyst

- No discoloration

- Firm, attached to underlying bone

- Eyelid abscess/Orbital cellulitis

- Neoplasm

- Rhabdomyosarcoma

- Leukemia/lymphoma

- Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- 50% of congenital NLDO resolve by 6 months of age.

- 90% resolve by one year of age.

- Small percentage still improves after one year of age.

- Symptoms can recur after few weeks of apparent resolution.

- Resolution can be incomplete with residual intermittent symptoms, especially with URI.

Nonsurgical treatment

- NLD massage

- Crigler method

- Index finger applies pressure over NL sac with downward rocking motion

- Occlusion of canaliculi important to assure increase of hydrostatic pressure down NLD

- Speeds resolution of NLDO (Kushner, Arch Ophthalmol 1982)

- Simple NLD massage

- Allows reflux of discharge out of canaliculi

- Might not help speed resolution, but can clear mucopurulence out NL sac temporarily

- Some see no benefit to massage — might introduce contamination in NLD area.

- Topical antibiotics

- Erythema of conjunctiva and/or eyelids

- Three days’ duration usually sufficient; longer duration for dacryocystitis

- Topical antibiotic ointments such as Erythromycin or Polymyxin B/Bacitracin ointment can be used with lacrimal massage. This will often improve the amount of symptomatic discharge but some authors feel it is not necessary to treat just based upon discharge in setting of quiet conjunctiva — normal flora

- Systemic antibiotics: for dacryocystitis/cellulitis (see Disease Related Complications below)

- Topical breast milk: used by some because of anti-infective and anti-inflammatory properties but no studies to support effectiveness

Surgical options

NLD probing:

- Office-based

- Avoid anesthesia risk

- Less cost — might be more cost-effective than delaying until one year of age and then performing procedure under anesthesia (PEDIG, Arch Ophthalmol 2012)

- 23 gauge irrigating cannula effective

- Earlier resolution of symptoms

- Early intervention does not allow for spontaneous resolution; some children are probed unnecessarily (up to 2/3 of NLDO patients probed at 6 months (PEDIG, Arch Ophthalmol 2012).

- No ability to do additional procedures: balloon dilation, stent insertion or turbinate infracture

- Might be painful to the patient

- Office probing should never be performed in the setting of bilateral dacryoceles because there is a high risk of intranasal cyst and office probing in the setting places an infant at risk for a compromised airway (Levin, Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003).

In OR with anesthesia:

- More surgical options and controlled surgical setting

- Metal-on-metal contact of probes beneath inferior turbinate important

- Fluorescein irrigation to confirm patency

- Approximately 70–96% success rates reported depending upon definition of success, age of patient and severity of obstruction (multiple references)

- Additional procedures possible if needed

- Higher cost

- Anesthesia risk

- Recent research suggesting neurotoxicity of general inhalational anesthesia in young children affecting CNS development (Good, JAAPOS 2014)

- Attempts should be made to limit anesthetic exposure in young children, thus primary stenting when NLD stenosis is found on probing and irrigation is indicated

Balloon dacryoplasty:

- Various options available; LacriCath most common (Quest Medical, Allen, TX)

- Balloon dilation of distal and proximal portions of NLD

- Substitute for NLD stents

- Indications

- Primary probing failure

- Severe stenosis encountered on primary surgery

- Down syndrome, craniofacial syndromes

- Routinely as primary procedure under anesthesia — some prefer standard probing in office setting only and reserve more aggressive techniques for OR.

- Older age group?

- Since literature suggests decreased effectiveness for simple probing over age 18 months (Katowitz, multiple references)

- PEDIG study showed success rate for simple probing not significantly different until after 35 months of age (PEDIG, Ophthalmology 2008)

- Effectiveness

- Controversy exists regarding the most effective treatment. Many options are effective

- PEDIG study showed 77% success of balloon compared with 84% success for stents for initial failed probings (PEDIG, Arch Ophthalmol 2009)

- Stenting as a primary procedure has been shown to have a very high success rate (96%) (Engel, JAAPOS 2007)

NLD stents:

- Indications: as above for dacryoplasty

- Bicanalicular

- Crawford, FCI Ritleng, Bika (FCI Ophthalmics, Pembroke, MA)

- Guibor (Beaver-Visitec International, Waltham, MA)

- Catalano (Katena Products, Denville, NJ)

- Stent passed through each canaliculus and down NLD into inferior meatus

- Securing tubes in nares

- Tied together with silk suture

- Tied in knot upon itself

- Tied with self-threading suture (Crawford)

- Anchored to retinal band/sponge

- Anchored to lateral wall of naris

- Leave untied

- Spontaneous dislocation possible

- Newer Lacriflow stent (Kaneka Pharma America, New York, NY) self-retaining and does not require anchoring or tying in nose

- Monocanalicular

- FCI Monoka, MonoCrawford, Masterka (FCI Ophthalmics Pembroke, MA) common options

- Anchored to punctum without suture

- Ideally should be placed in the upper eyelid punctum as this sits further from the corneal limbus in most patients when compared to the lower eyelid.

- Prospective study showed no difference in outcomes between monocanalicular and bicanalicular stenting (Andalib, J AAPOS. 2010)

- Effectiveness: similar to that of balloon dilation

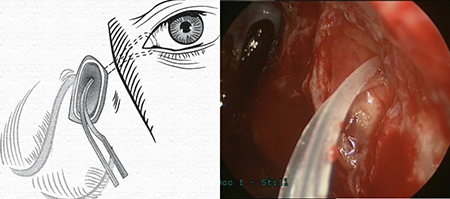

Dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) (Figure 5):

- Indicated for failure of standard probing, balloon dilation and/or stents

- Higher failure rate in children due to scarring of ostomy, concomitant allergy

- External approach

- Success rates reported 88–94%

- Advantages:

- Easier for less experienced surgeon

- Bleeding more easily controlled

- Larger osteotomy can be created

- Disadvantages:

- External scar

- Might require revision if osteotomy occludes

- Possible role of adjunctive MMC to prevent fibrosis

- Endonasal approach

- Can be performed using standard intranasal techniques or laser assisted

- Can be done with intranasal balloon dilation (Silbert, Orbit. 2010)

- Absent punctum/canaliculus: could require conjunctivodacryocsytorhinostomy (CJDCR) with Jones tube if no ability to intubate canaliculi

- High failure rate in children

- Dislocation of tube common

- Obstruction of tube also common

- Frequent revisions might be necessary.

Figure 5. Dacrocystorhinostomy with Crawford tubes in middle meatus (Dacrocystorhinostomy, American Rhinologic Society, 2015).

Other management considerations

- Therapeutic infracture of turbinates

- Could aid in success of NLDO surgery if tight inferior meatus appreciated from hypertrophied inferior turbinate

- Freer elevator or hemostat used to manually move inferior turbinate medially, away from NLD outlet

- No studies have shown definitive benefit compared to standard probing (Attarzadeh, Eur J Ophthalmol 2006)

- Nasal endoscopy

- Primarily technique mastered by ENT, but some ophthalmologists have learned as well

- Usefulness

- Locating probe if cannot appreciate metal-on-metal contact

- Retrieving NLD tube

- Evaluating inferior turbinate for hypertrophy

- During DCR procedure

- Excision of NLD fistula

- Fistulas more common in Down syndrome

- NLD fistula should be treated if patent with active tearing or discharge

- Some can spontaneously close after treatment of concurrent NLD obstruction (Al-Salem, Br J Ophthalmol. 2014).

- Excision of NLD fistula alone or in combination with NLD probing, tubes, DCR depending upon findings (Al-Salem, Br J Ophthalmol. 2014)

- Punctal/canalicular atresia

- Mild veil covering punctum can be punctured and dilated successfully in most cases

- Stenosis of canaliculus

- Postviral or trauma

- Wide dilation might suffice.

- Three-snip procedure helpful if more severe

- Punctal/canalicular agenesis

- Dacryocystography can be helpful to locate patent canaliculi but not easy to perform in children

- Cut-down adjacent to any noticeable papilla or 8 mm lateral to canthal angle

- Probing and intubation

- Common canalicular agenesis/obstruction

- Canaliculodacryocystorhinostomy (CLDCR) — anastomosis from patent area of common canaliculus to lacrimal sac and through a DCR ostium

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

- Overall 70–96% success of NLD probing, mostly around 90% (multiple references)

- Success of probing decreases slightly with increasing age, especially after 36 months (multiple studies)

- Success of probing decreases with more proximal obstructions

- Some advocate preoperative oral and topical antibiotics as well as postoperative oral and topical steroids to optimize surgical outcome, particularly for balloon dilation (Becker, Am J Ophthalmol. 1996). This, however, is controversial.

- Some advocate the use of antimetabolites, such as Mitomycin C to prevent DCR rhinostomy closure, either routinely or for cases of initial failure

- Failed initial NLD probing

- PEDIG found repeat probing after initial failure low success rate around 50% (PEDIG, J AAPOS. 2009)

- Proceed with balloon dacryoplasty or stent depending upon preference

- Reserve DCR for after failed balloon or stent

- Some suggest step-wise approach to surgical management regardless of age or symptoms (Casady, Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006)

- Best practice might be to tailor approach based on severity of symptoms, patient age, intraoperative findings; more aggressive initial procedure might reduce need for reoperation (ie. primary balloon or stenting).

- Stent removal strategy

- Leave stents in for 3–6 months before removal.

- PEDIG study showed decreased success rate if removed less than 2 months postoperatively (PEDIG, Arch Ophthalmol. 2009).

- Removal in office for monocanalicular

- Bicanalicular stents can be removed in office if not anchored in nose, small knot in tubes, rotate knot out of punctum before cutting tube.

- Failed DCR

- KTP laser of closed ostium with silicone reintubation

- Balloon dilation of ostium with silicone reintubation

- Consider endoscopic examination and possible revision.

- If there is a membranous covering over the valve of Rosenmuller, a Sisler trephine (BD Visitec) can be used to lyse this.

- Repeat DCR.

- Down syndrome

- Higher incidence of complicated NLDO and thus poor response to standard probing (Coats, Ophthalmology. 2003)

- Suggestion of balloon dacryoplasty or NLD stent for initial procedure (Lueder, J AAPOS. 2000)

- Monocanalicular tubes more likely to cause corneal erosions—abnormal lid position?

- Also consider nasal steroids and reduction of inferior turbinate for treatment failures.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

False passage during NLD probing

- Prevention

- Pass probes without excessive force

- Anticipate abnormal anatomy in Downs, craniofacial syndromes

- Ensure complete passage into inferior meatus

- Do not pass smaller than #00 Bowman probe along canaliculus or down NLD—thinner probes can puncture tissue more easily (unless an office probing in an infant is being performed)

- Management

- Usually none required except to complete proper probing procedure to ensure successful result and allow false passage to heal spontaneously

Excessive bleeding after procedure

- Prevention

- Pack nose with decongestant-soaked (eg. oxymetazoline) cottonoids before more involved nasal-manipulating procedures such as turbinate infracture, stent placement, DCR

- Minimize nasal mucosa trauma

- Nasal speculum or endoscope to help locate stents before retrieval

- Endoscopic approach with DCR

- Limit use of NSAIDs postoperatively

- Management

- Elevation of head

- Cold compresses

- Nasal packing

- Cautery if needed

Spontaneous dislocation of tubes

- Prevention

- Anchor monocanalicular tubes properly in punctum

- Anchor bicanalicular tubes within nose

- Management

- Attempt rethreading of bicanalicular tubes in office

- Remove tubes

Erosion of punctum from bicanalicular tubes

- Prevention

- Test tension of tubes after insertion—should have enough slack such that no discernable tension at level of punctum but also no contact of tubes with cornea

- Avoid anchoring tubes within nose

- Avoid over-dilating each punctum as this tears the orbicularis fibers that surround the punctum and increases the risk of punctual slitting

- Management

- Reinsert new tubes if more than half of length of canaliculus has been slit by tubes

- Leave tubes in place until scheduled removal if only minor erosion

Abrasions from monocanalicular tubes

- Prevention

- Make sure collarette firmly anchored into punctum

- Avoid using in Down syndrome, other abnormal eyelid anatomy

- Always attempt to place monocanalicular stents in the upper eyelid

- Management

- Remove tube

- Topical antibiotic/steroid

Granuloma formation on punctum after stent insertion

- Prevention

- Antibiotic/steroid postoperatively

- Management

- Excision or cautery of granuloma

Disease-related complications

Anisometropic amblyopia

- Recent evidence suggests association between anisometropic amblyopia and unilateral/asymmetric NLDO (Kipp, J AAPOS 2013)

- Cycloplegic refraction should be performed as part of NLDO evaluation

- Follow up children with amblyogenic risk factors

- Could early intervention or early spontaneous resolution of NLDO reduce amblyogenic risk factors?

Dacryocystocele and dacryocystitis

- Early intervention of dacyocystocele recommended:

- Massage frequently

- Probing (office or OR) within first few weeks if not resolving even in absence of infectious symptoms

- Always avoid office probing for bilateral cases (risk of airway obstruction due to intranasal cyst)

- Approximately 50% of cases can be managed without need for general anesthesia: antibiotics, massage, office-based probing (Dagi, J AAPOS 2012

- Earlier surgical intervention could prevent dacryocystitis and prevent need for further intervention (Becker, Am J Ophthalmol. 2006)

- Stent or balloon dilation might be required.

- ENT consult if nasal congestion symptoms to rule out intranasal cyst

- Marsupialization of cyst

- Check both nares, higher incidence of bilateral involvement

- Dacryocystitis/cellulitis requires aggressive management

- Systemic (IV if appears septic) antibiotics for gram positive and gram negative organisms

- Topical antibiotics

- Antibiotics before surgical treatment increases success rate (Baskin, J AAPOS. 2008)

- Possible tapping of NL sac with tuberculin needle for immediate relief and cultures

- Probing after infection controlled or after few days of antibiotics if not responding

- Some advocate immediate probing—beware false passage more common with acute inflammation

Historical perspective

- Sir William Bowman (1816–1892)

- British histologist, ophthalmologist, and surgeon known for studies on eye, kidney, and striated muscle

- Bowman probes named after him

- Many structures attributed to his discovery, eg. Bowman capsule, Bowman gland, Bowman membrane.

- Crigler

- Described first method of NLD massage in 1923

- Massage treatment still primary nonsurgical intervention for congenital NLDO

- Crawford

- Advanced silicone intubation of NLD system in 1970. This had been previously developed by Bruno Fayet, a French ophthalmologist

- Monoka

- Monocanalicular stents as alternative to bicanalicular

- Becker

- Balloon dacryoplasty developed 1990s as alternative to stent placement

References and additional resources

- AAPOS: Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

- EyeWiki: Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction, Congenital

- Video: Endoscopic DCR

- Video: NLD probing and bicanalicular Crawford tube insertion

- Aldahash FD, Al-Mubarak MF, Alenizi SH, Al-Faky YH. Risk factors for developing congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jan;28(1):58-60

- Ali MJ, Kamal S, Gupta A, Ali MH, Naik MN. Simple vs complex congenital nasolacrimal duct obstructions: etiology, management and outcomes. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015 Feb;5(2):174-7

- Al-Salem K, Gibson A, Dolman PJ.Management of congenital lacrimal (anlage) fistula. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014 Oct;98(10):1435-6

- Andalib D, Gharabaghi D, Nabai R, Abbaszadeh M. Monocanalicular versus bicanalicular silicone intubation for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2010 Oct;14(5):421-4

- Arora S, Koushan K, Harvey JT. Success rates of primary probing for congenital nasolacrimal obstruction in children. J AAPOS. 2012 Apr;16(2):173-6

- Attarzadeh A, Sajjadi M, Owji N, Reza Talebnejad M, Farvardin M, Attarzadeh A. Inferior turbinate fracture and congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006 Jul-Aug;16(4):520-4.

- Baran F, Kelly JP, Finn LS, Manning S, Herlihy E, Weiss AH. Evaluation and treatment of failed nasolacrimal duct probing in Down syndrome. J AAPOS. 2014 Jun;18(3):226-31

- Barnes EA, Abou-Rayyah Y, Rose GE. Pediatric dacryocystorhinostomy for nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2001 Sep;108(9):1562-4

- Baskin DE, Reddy AK, Chu YI, Coats DK. The timing of antibiotic administration in the management of infant dacryocystitis. J AAPOS. 2008 Oct;12(5):456-9

- Becker BB. The treatment of congenital dacryocystocele. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006 Nov;142(5):835-8

- Becker BB, Berry FD, Koller H. Balloon catheter dilatation for treatment of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996 Mar;121(3):304-9

- Campolattaro BN, Lueder GT, Tychsen L. Spectrum of pediatric dacryocystitis: medical and surgical management of 54 cases. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1997 May-Jun;34(3):143-53

- Casady DR, Meyer DR, Simon JW, Stasior GO, Zobal-Ratner JL. Stepwise treatment paradigm for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jul-Aug;22(4):243-7

- Celenk F, Mumbuc S, Durucu C, Karatas ZA, Aytaç I, Baysal E, Kanlikama M. Pediatric endonasal endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013 Aug;77(8):1259-62

- Coats DK, McCreery KM, Plager DA, Bohra L, Kim DS, Paysse EA. Nasolacrimal outflow drainage anomalies in Down’s syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2003 Jul;110(7):1437-41

- Dagi LR, Bhargava A, Melvin P, Prabhu SP. Associated signs, demographic characteristics, and management of dacryocystocele in 64 infants. J AAPOS. 2012 Jun;16(3):255-60

- Dei Cas RE. Evaluation of Tearing in Children. In: Katowitz JA, ed. Pediatric Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, Springer-Verlag, 2002.

- Engel et al, Monocanalicular silastic intubation for the initial correction of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2007 Apr;11(2):183-6. Epub 2007 Feb 15

- Good WB. Is anesthesia safe for young children? JAAPOS 2014; 18(6): 519-520

- Heher KL, Johnson MA, Katowitz JA. Management of Pediatric Upper System Problems: Conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy. In: Katowitz JA, ed. Pediatric Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, Springer-Verlag, 2002.

- Jones JT, Wobig JL, editors. Surgery of the eyelids and lacrimal system. Birmingham: Aesculapius; 1976. p. 157–63.

- Katowitz JA, Low JE, Covici SJ, Goldstein JB. Management of Pediatric Lower System Problems: Probing and Silastic Intubation. In: Katowitz JA, ed. Pediatric Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, Springer-Verlag, 2002.

- Katowitz JA, Welsh MG. Timing of initial probing and irrigation in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmology. 1987 Jun;94(6):698-705

- Kipp MA, Kipp MA Jr, Struthers W. Anisometropia and amblyopia in nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2013 Jun;17(3):235-8.

- Kropp TM, Goldstein JB, Katowitz WR. Management of Pediatric Lower System Problems: Dacryocystorhinostomy. In: Katowitz JA, ed. Pediatric Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, Springer-Verlag, 2002.

- Levin AV et al. Nasal endoscopy in the treatment of congenital lacrimal sac mucoceles. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003 Mar;67(3):255-61.)

- Low JE, Johnson MA, Katowitz JA. Management of Upper System Problems: Punctal and Canalicular Surgery. In: Katowitz JA, ed. Pediatric Oculoplastic Surgery. New York, Springer-Verlag, 2002.

- Lueder GT. Treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction in children with trisomy 21. J AAPOS. 2000 Aug;4(4):230-2

- Matta NS, Silbert DI. High prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in preverbal children with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2011 Aug;15(4):350-2

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial comparing the cost-effectiveness of 2 approaches for treating unilateral nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012 Dec;130(12):1525-33

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Balloon Catheter Dilation and Nasolacrimal Intubation for Treatment of Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction Following a Failed Probing. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009; 127: 633–639

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Primary treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction with probing in children younger than 4 years. Ophthalmology. 2008 Mar;115(3):577-584

- Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Repeat probing for treatment of persistent nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J AAPOS. 2009;13:306-307

- Rajabi MT, Abrishami Y, Hosseini SS, Tabatabaee SZ, Rajabi MB, Hurwitz JJ. Success rate of late primary probing in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2014 Nov-Dec;51(6):360-2

- Robb RM. Success rates of nasolacrimal duct probing at time intervals after 1 year of age. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1307–9

- Sathiamoorthi S, Frank RD, Mohney BG. Incidence and clinical characteristics of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018 [Epub ahead of print]

- Sathiamoorthi S, Frank RD, Mohney BG. Spontaneous resolution and timing of intervention in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018 [Epub ahead of print].

- Silbert DI, Matta NS. Outcomes of 9 mm balloon assisted endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: retrospective review of 97 cases. Orbit. 2010 Feb;29(1):25-8

- Stager D, Baker JD, Frey T, Weakley DR Jr, Birch EE. Office probing of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992 Jul;23(7):482-4

- The treatment of congenital dacryocystitis. JAMA. 1923, 81: 23-24.

- Thongthong K, Singha P, Liabsuetrakul T. Success of probing for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in children under 10 years of age. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009 Dec;92(12):1646-50

- Waladis EJ, Aakalu VK, Yen MT, Bilyk JR, Sobel RK, Mawn LA. Balloon dacryoplasty for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2018 [Epub ahead of print].

- Wong RK, VanderVeen DK. Presentation and management of congenital dacryocystocele. Pediatrics. 2008 Nov;122(5):e1108-12.