The Enophthalmos Syndromes

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

3 primary diagnoses

- Giant fornix syndrome (GFS)

- Silent sinus syndrome (SSS)

- Silent brain syndrome (SBS)

Etiology

The common factor in these 3 conditions is an alteration of the volumetric relationship between the bony orbit and its soft tissue contents.

In SSS the orbital bony volume is increased due to contraction and atrophy of a chronically infected maxillary sinus, causing the orbital floor to descend.

In SBS the orbital bony volume is also increased, but in this case the orbital roof is pulled up, as a result of ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunting early in life, the reduction of intracranial pressure pulling up the orbital roof (Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114:1206).

GFS, most commonly seen in the elderly, is caused by a reduction in orbital soft-tissue volume, mostly from loss of fat, perhaps due to blepharoplasty surgery or age-related fat atrophy, causing a deep dead space to be created in the fornices, where colonization with bacteria and fungus occurs (Ophthalmology 2004; 111:1539).

- “Senile sunken upper lids” is another term for GFS.

- “Prostaglandin associated periorbitopathy” is a variant of this disease.

- In addition to fat atrophy, from direct suppression of adipogenesis by prostaglandins, Muller’s muscle is also stimulated by prostaglandins, with lid retraction and lagophthalmos as additional causes of chronic ocular irritation (OPRS 2012; 28:e33).

- In the original description of GFS all 12 patients had Staphylococcus aureus colonization of their fornices as evidenced by culture (Ophthalmology 2004; 111:1539).

- There can be overlap between the enophthalmos syndromes; SBS can cause GFS (Cornea 2012; 31:1065).

- An aspergilloma developed in the deep fornix of an adult who had undergone VP shunting as a child and had developed SBS (Cornea 2012; 31:1065).

- This patient developed fungal keratitis, which led to enucleation; the aspergilloma was not discovered until the enucleation.

Epidemiology

Too few cases have been described in the literature for accurate epidemiologic data on GFS, but data from case series can be cited.

- In a series of 6 cases there were 4 women and 2 men with an age range of 61–85 (OPRS 2013; 29:63).

- In another series of 5 cases the mean age was 75 years (range 70–95) and all patients were female (OPRS 2012; 28:4).

- In the original description of 12 cases the mean age was 85 (range 77–93) and 10 were female (Ophthalmology 2004; 111:1539).

Very few cases of SBS have been described in the literature.

- In the original description there were 2 patients aged 24 and 25 years who had undergone VP shunting in their teens (OPRS 2009; 25:434).

- The disease can present in the fourth decade and VP shunting can have taken place in infancy (Cornea 2012; 31:1065).

SSS can present throughout life.

- In the original description there were 19 patients with mean age 36 years (range 29–46), (Ophthalmology 1994;101:772).

History

With GFS, the complaints are primarily related to chronic unilateral relapsing conjunctivitis.

- In addition to the discharge there might be symptoms of chronic irritation and dryness.

- Patients might be aware of chronic discharge and injection.

- In the prostaglandin analogue there is glaucoma treated with prostaglandin analogues or Latisse (bimatoprost 0.03%) has been used for hypotrichosis.

With SBS there is a history of VP shunting at a young age.

With SSS the only complaint is the asymmetry, but displacement of the globe does not usually cause visual symptoms (Figure 1).

- There is a case report of vertical diplopia due to SSS, worse on upgaze. (OPRS 2013; 29:e130).

- However, the patient presented with a one day history of diplopia, there was periocular pain, hypertropia and elevation deficit were noted on examination, orbital imaging showed maxillary sinusitis, with a normal orbital floor and the SSS was evident on CT scan one year later.

- Therefore, visual symptoms including diplopia, and periocular pain might be from the causative process of infection and inflammation rather than the secondary enophthalmos and globe displacement.

- There might be a history of treatment for chronic sinusitis.

- Patients might be unaware of the asymmetry and the sinus disease.

- There might be other causes of acquired and congenital asymmetry and the SSS might be contributory.

- History of trauma, especially blunt trauma and orbital fracture repair

- Radiotherapy to the periocular region and/or orbit

Figure 1. Silent sinus syndrome.

Clinical features

In GFS the primary clinical feature is chronic discharge and conjunctival injection (Figure 2).

- Deep superior fornix with evidence of bacterial colonization

- The inferior fornix might be involved in GFS (OPRS 2007; 23:256).

- The sunken and elongated superior fornix can create the appearance of involutional ptosis.

Figure 2. Giant fornix syndrome.

SBS can cause severe keratopathy due to lagophthalmos and upper lid entropion (OPRS 2009; 25:434).

In SSS the primary clinical features are enophthalmos, hypoglobus and asymmetry of the maxillary sinus buttress.

- There might be other secondary causes of ocular surface abnormalities including poor eyelid apposition to the globe, resulting in exposure keratopathy.

- In rare cases, SSS can involve a sinus other than the maxillary sinus.

- Frontal sinus atelectasis can cause hyperglobus (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013; 148: 354).

- Ethmoid sinus atelectasis can cause medial displacement of the globe (J Laryngol Otol 2010;124:206).

In GFS there might be other involutional changes causing eye irritation, such as upper lid horizontal laxity with the rubbery changes of floppy eyelid syndrome.

- Hypertrichosis and increased pigmentation of periocular skin with prostaglandin analogue use

- Periocular change can occur within 3 months of regular use of prostaglandin analogue eye drops.

Testing

For GFS, culture of the fornix is helpful; important variants of bacterial colonization such as pseudomonas and methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (OPRS 2012; 28:4) might be recognized.

- Although not indicated to establish the diagnosis of GFS, CT scan might show air collecting between the conjunctiva and the lid (Eye 2006; 20:1481).

- This air collection has led to misdiagnosis, such as after trauma when it can be mistaken for a sign of ocular or orbital penetration (J Emerg Med 2013; 44:e311).

For SBS, imaging shows loss of volume above the orbital roof and superior bowing.

For SSS, imaging shows asymmetry of the orbital floor.

- CT imaging demonstrates opacification and decreased bony volume of the ipsilateral maxillary sinus with inferior bowing of the orbital floor.

Risk factors

- Aging/blepharoplasty

- VP shunting

- Chronic sinusitis

Differential diagnosis

- Progressive enophthalmos can be caused by orbital infiltration with metastatic breast carcinoma (Surg Neurol 1998;50:600).

- It can be bilateral and can be the presenting sign of metastatic breast carcinoma even when local symptoms in the breast are absent (OPRS 2005; 21:311).

- Cicatrizing conjunctival disease can cause contraction and entropion, which appear similar to enophthalmos syndromes (Cornea 2012; 31:1065).

- Paget disease can cause thickening of the orbital rim creating the appearance of enophthalmos (OPRS 2002;18:388).

- Late after orbital decompression, some thyroid eye disease patients develop progressive enophthalmos by a similar mechanism to SSS.

- Obstruction of the ethmoidal infundibulum caused by prolapsed orbital fat causes reduced aeration and contraction of the maxillary sinus (Ophthalmology 2003; 110:819).

- Floppy eyelid syndrome

- Enophthalmos is a frequent feature of HIV-associated soft-tissue atrophy and lipodystrophy (HIV Med 2004;5:448).

- Hemifacial atrophy as an unrecognized cause of underlying facial asymmetry in SSS and SBS.

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

GFS is a chronic condition, with some limit to the degree of fornix elongation.

- Some periocular changes associated with prostaglandin analogue use might partially resolve after discontinuing drops.

SBS has some limit to the degree of bony change in the orbital roof.

SSS is limited by the degree of maxillary sinus atelectasis.

Medical therapy

With GFS, to eradicate the colonization, treatment might need to be more aggressive than for routine bacterial conjunctivitis.

- The superior fornix might need to be cleaned mechanically and regularly rinsed to clear the colonizing organisms.

- Some patients need long-term maintenance topical antibiotics.

- Rotating antibiotics might be needed (OPRS 2007; 23:256).

- Regular irrigation with dilute povidone might be helpful (Cornea 2011; 30:479).

There is no medical treatment for SBS or SSS.

Surgery

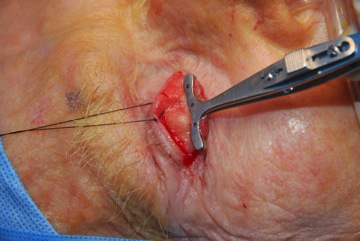

For GFS, if medical therapy is unsuccessful or produces unacceptable morbidity, surgical shortening and resection of redundant superior fornix conjunctiva might be necessary (OPRS 2013; 29:63) (Figure 3).

- Ptosis repair for involutional stretching of the levator aponeurosis and Muller’s muscle might also be helpful (OPRS 2010; 26:172).

- Elongation of the superior sulcus with involutional ptosis and upper lid stretching contributes to the deepened fornix.

For SBS, the orbital volume might be augmented.

For SSS, a combined ENT/orbital approach is best.

- Endoscopic maxillary antrostomy is combined with elevation of the collapsed orbital floor, by a transconjunctival approach as performed for a traumatic blowout fracture (Laryngoscope. 2001; 111:975).

Figure 3. Surgical shortening and resection of redundant superior fornix conjunctiva.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

GFS should be treatable once recognized.

SBS and SSS can be partially corrected, but normal bony anatomy cannot be restored.

Disease-related complications

In GFS, the primary concern is secondary keratitis from chronic discharge.

SSS and SBS pose cosmetic concerns, with severe cases causing chronic ocular irritation.

Historical perspective

Giant fornix syndrome was described by Rose in 2004.

The association between reduced intracranial pressure and acquired enophthalmos was first described by Haik in 1993 (J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1993;13:171)

The term silent brain syndrome has more recently been adopted (OPRS 2009; 25:434).

Silent sinus syndrome was first described in 1964 by Montgomery (Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon 1964; 43:41), in 2 patients in whom mucocele of the maxillary sinus was thought to be the cause.

The term silent sinus syndrome was adopted as the association with maxillary sinus atelectasis became clear (Ophthalmology 1994;101:772).

References and additional resources

- Bernardini FP, Rose GE, Cruz AA, Priolo E: Gross enophthalmos after cerebrospinal fluid for childhood hydrocephalus: The “silent sinus syndrome”. OPRS 2009; 25:434.

- Chen JJ, Cohen AW, Wagoner MD, Allen RC: The “Silent Brain Syndrome” creating a severe form of the “Giant Fornix Syndrome”. Cornea 2012; 31:1065.

- Cruz AA, Mesquita IM, de Oliveira RS. Progressive bilateral enophthalmos associated with cerebrospinal shunting. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:152.

- Czyz C, Kondapalli SSA, Mazzuca DE, et al: Variant of giant fornix syndrome masquerading as intraocular free air on computed tomography. J Emerg Med 2013; 44:e311.

- Goncalves ACP, Moura FC, Monteiro MLR: Bilateral progressive enophthalmos as the presenting sign of metastatic breast carcinoma. OPRS 2005; 21:311.

- Haik BG, Pohlod M. Severe enophthalmos following intracranial decompression in a von Recklinghausen patient. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1993;13:171–4.

- Hardy TG, McNab AA. Bilateral enophthalmos associated with paget disease of the skull: a case report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;18:388.

- Jones DF, Lyle CE, Fleming JC. Superior conjunctivoplasty-mullerectomy for correction of chronic discharge and concurrent ptosis in the anophthalmic socket with enlarged superior fornix. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 26:172.

- Jones LD, Ghosh Y, Ahluwalia H, Robinson R: Iatrogenic giant fornix syndrome of the lower eyelid. Opthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2007; 23:256.

- Kuzma BB, Goodman JM. Slowly progressive bilateral enophthalmos from metastatic breast carcinoma. Surg Neurol 1998;50:600.

- McArdle B, Perry C. Ethmoid silent sinus syndrome causing inward displacement of the orbit: case report. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124:206.

- Merchante N, García-García JA, Vergara S, et al. Bilateral enophthalmos as a manifestation of HIV infection-related lipoatrophy. HIV Med 2004;5:448.

- Meyer DR, Nerad JA, Newman NJ, et al: Bilateral enophthalmos associated with hydrocephalus and ventriculoperitoneal shunting. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114:1206.

- Nabavi CB, Long JA, Compton CJ, Vicinanzo MG. A novel surgical technique & for the treatment of giant fornix syndrome. OPRS 2013; 29:63.

- Naik RM, Khemani S, Saleh HA: Frontal silent sinus syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013; 148: 354.

- Noma K, Kalzaki H: Bilateral upper eyelid retraction caused by topical bimatoprost therapy. OPRS 2012; 28:e33).

- Rose GE: The giant fornix syndrome: an unrecognized cause of chronic, relapsing, grossly purulent conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 2004; 111:1539.

- Rose GE, Lund VJ: Clinical features and treatment of late enophthalmos after orbital decompression. A condition suggesting cause for idiopathic “imploding antrum” (silent sinus) syndrome. Ophthalmology 2003; 110:819.

- Saffra N, Rakhamimov A, Saint-Louis L, Wolinitz RJ: Acute diplopia as the presenting sign of silent sinus syndrome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2013; 29:e130.

- Sobel RK, Tienor BJ: The coming age of enophthalmos. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2013; 24:500).

- Soparkar CNS, Partinely JR, Cuaycong MJ, et al. The silent sinus syndrome: a cause of spontaneous enophthalmos. Ophthalmology 1994;101:772.

- Taylor JB, Fintelmann RE, Jeng BH. Subconjunctival injections and povidone-iodine washings for the treatment of giant fornix syndrome. Cornea 2011; 30:479.

- Turner SJ, Sharma V, Hunter PA. Giant fornix syndrome: a recently described cause of chronic purulent conjunctivitis and severe ocular surface inflammation, with a new diagnostic sign on CT. Eye 2006; 20:1481.

- Vander Meer JB, Harris G, Toohil RJ, Smith TL. The silent sinus syndrome: a case series and literature review. Laryngoscope. 2001; 111:1975.