Eyelid Retraction

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Eyelid retraction is a displacement of the upper eyelid superiorly or lower eyelid inferiorly through a variety of mechanisms.

Causes

- Vertical shortening of the skin either through acute inflammatory changes or chronic shortening due to long standing inflammation or physical deficit caused by surgery or trauma

- Contraction of the conjunctiva through acute inflammatory changes or chronic shortening due to long standing inflammation or physical deficit caused by surgery or trauma

- Shortening of the tissues between the skin and conjunctiva, such as the orbital septum, usually secondary to surgery or trauma

- Important to rule out cicatrizing malignancy such as metastatic scirrhous breast carcinoma

- Neuromuscular

- Graves orbitopathy — strong evidence for multifactorial origins, including sympathetic effects of hyperthyroidism, inflammation of retractor muscles, overreaction of superior rectus and levator in response to inferior rectus restriction, fibrosis of retractors (Survey of Ophthalmology 2013; 58(1))

- Nonthyroid inflammation of eyelid retractors, e.g. Sarcoidosis (Arch Ophthalmol 2006; 124)

- Dorsal midbrain lesions (Colliers sign) (Review Neurologique 2014; 170:464-470)

- Orbicularis weakness in upper or lower eyelid (e.g., facial nerve palsy)

- Mechanical effects

- Prominence of globe, such as can occur with severe myopia, buphthalmos, dysthyroid disease, cherubism, craniosynostosis, or Paget’s disease (Ophthalmology 1996; 103:168-176)

- Anophthalmia (Ophthal Plast Recontr Surg 2014; 30(4))

- Prostaglandin analogue induced orbitopathy (in part through fat atrophy) (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg November 2014)

- Topical bimatoprost therapy (reversible) (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2012; 28(2))

- Negative vector eyelid (Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2014; 34(7):995-1004)

- Orbit/lower eyelid volume deficiency (Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2014; 34(7): 995-1004)

- Congenital issues

- Preterm infant-transient conjugate downward gaze with upper eyelid retraction (Pediatr Neurol 1994; 10:313-316)

- Eye popping reflex in normal infants when ambient light levels are suddenly reduced (J. Pediatr 1972; 81:87-89)

- Congenital eyelid retraction (BJO, 1990; 74:542-544)

- Epiblepharon (Korean J Ophthal 2010; 24(1):4-9)

- Congenital, paradoxical lower eyelid retraction on upgaze (OPRS 115(5):100-105)

- Pseudorectraction due to contralateral ptosis (Herring law)

Epidemiology

Skin shortage

Inflammatory causes of skin shortening include atopy and rosacea.

Other causes of periorbital dermatitis are less likely to cause retraction.

- Contact dermatitis is usually more acute.

- Seborrheic dermatitis is confined to hair-bearing and oily areas of head and neck.

- Psoriasis usually affects primarily eyelid margin.

Largely genetic causes of skin shortage include scleroderma and ichthyosis.

Physical/mechanical skin shortage can result from

- Blepharoplasty

- Eyelid tumor removal

- Laser resurfacing

- Radiation

- Actinic damage

- Chemical/thermal burns

- Trauma

Conjunctival shortage

Conjunctival cicatrization can result from

- Trauma

- Medication

- Infections

- Systemic bullous disease

- Autoimmune disease

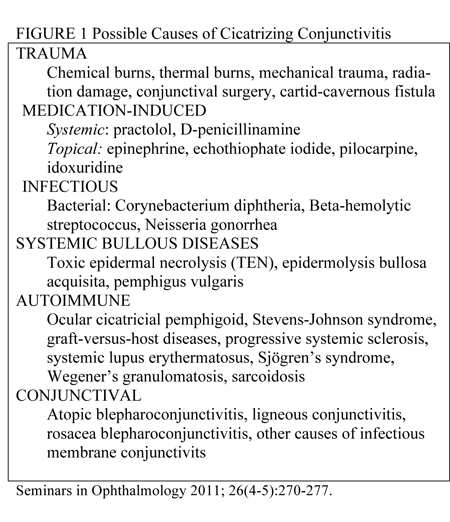

- Other conjunctival diseases (Figure 1) (Seminars in Ophthalmology 2011; 6(4-5): 270-277)

Middle lamella shortage

This results from injury to the septum through trauma or surgery, e.g., anterior approach to posterior eyelid compartments followed by scarring, particularly in the plane of the inelastic septum.

History

- Speed of onset helpful — acute onset entities can resolve with medical management, e.g., inflammatory

- History of infectious disease, e.g., staph blepharitis

- Atopic history — childhood eczema can progress to adult atopic dermatitis

- Rosacea history including

- Erythema

- Telangiectasia

- Papulopustular eruptions

- Rhinophyma

- Chemical or thermal burn including

- Laser resurfacing

- Chemical peels

- Trauma or facial surgery, whether transcutaneous or transconjunctival, e.g., blepharoplasty or blowout fracture repair

- Sun exposure/tanning

- Skin neoplasms

- Congenital, e.g., blepharophimosis

- History of conjunctival inflammation (Figure 1)

- Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid

- Steven Johnson syndrome

- Underlying systemic disease such as thyroid disease

- Medications such as prostaglandin analogue drops (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg November 2014) or drops associated with cicatrizing conjunctivitis (Figure 1)

- Known scirrhous carcinoma, such as breast or gastrointestinal carcinoma

Clinical features

- Lower eyelid is inferiorly displaced or upper eyelid is superiorly displaced, inadequately covering and protecting the eye.

- Signs of cutaneous inflammation include

- Stigmata of rosacea

- Erythematotelangiectatic changes

- Papulopustular changes

- Rhinophyma

- Meibomian gland dysfunction, conjunctivitis

- Blepharitis

- Dry scales

- Eyelid margin keratinization, thickening, redness

- Signs of cutaneous scarring

- Trauma scars

- Tumor with loss of adnexal structures

- Previous surgery scars

- Lateral canthal dystopia, rounding

- Signs of conjunctival contracture

- Symblephara

- Blunting of fornices

- Signs of trachoma — superior tarsal involvement, Arlt’s line

- Stigmata of thyroid disease, e.g., increased vascularity near extraocular muscle insertion

- Eyelid can be stiff or “tethered” to the rim with middle lamellar scarring

- Inferior keratoconjunctivitis

- Lagophthalmos

- Ectropion

Testing

- Culture of eyelid margin if infection suspected

- Biopsy of skin if cutaneous tumor suspected

- If unexplained conjunctival contraction present, biopsies to investigate for ocular cicatrical pemphigoid

- Biopsy upper bulbar conjunctiva if possible

- Consider buccal mucosa biopsy at same sitting — low risk and can be positive despite negative conjunctival biopsy.

- Michel’s medium for direct immunofluorescence

- If clinical findings are definitive at time of biopsy, commence 4 weeks of topical steroids (Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97(4)).

- Graves orbitopathy

- Serology in patients in whom the diagnosis is not in doubt

- The only testing that is necessary is measurement of

- Serum thyrotropin (TSH)

- Free thyroxine

- Possibly TSH receptor (TSHR) antibodies

- There is some evidence TSH receptor antibodies can be helpful in

- Confirming the diagnosis

- Assessing the severity of the condition

- Monitoring the patient’s response to treatment

- Imaging with CT, MRI, or ultrasound. (UptoDate, Davies) (J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91(9):3464-3470) (J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83(11))

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

Eyelid retraction, particularly lower eyelid retraction, is often the result of multiple factors and the relative contributions need to be ascertained as part of the clinical evaluation.

- Middle lamellar scarring — “a forced traction test,” resistance to upward pulling on the eyelid

- Anterior lamellar shortage — increasing retraction on looking up and/or mouth opening

- Orbit/lower lid volume deficiency — subjective measurement

- Negative vector — observation that the cornea projects more anteriorly than the midface

- Lower lid laxity — “snapback test,” distraction test

- Orbicularis weakness — examiner’s ability to pry the patient’s eyelid open during forceful eyelid closure (Aesthetic Surgery Journal 2014; 34(7):995-1007)

Risk factors

Actinic skin damage

- Cumulative ultraviolet exposure

- Fitzpatrick skin type — system developed by Thomas B. Fitzpatrick as a way to classify response of different skin to ultraviolet light — types I–V are more prone to burning.

Atopy

- Family history of atopy remains most important risk factor for atopy in children (J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998; 101(5):587-593)

- Food and aeroallergies, microbes including S. aureus and Malassezia yeasts, contact allergens and autoallergens have been identified as atopic dermatitis triggers. (Trigger Factors, Allergens and Allergy Testing in Atopic Dermatitis, Evmorfia Ladoyanni, Atopic Dermatitis — Disease Etiology and Clinical Management; www.intechopen.com; Edited by Dr. Jorge Esparza-Gordillo, publisher InTech; online 02/22/2012, in print February 2012)

Rosacea

Rosacea is a common cause of skin inflammation, and common triggers (per National Rosacea Society survey) include

- Sun exposure, 81%

- Emotional stress, 79%

- Hot weather, 75%

- Wind, 57%

- Heavy exercise, 56%

- Alcohol consumption, 52%

- Hot baths, 51%

- Cold weather, 46%

- Spicy foods, 45%

- Humidity, 44%

Periorbital dermatitis of other causes

- Psoriasis — periorbital involvement less common and usually prevalent at eyelid margin

- Contact dermatitis — less commonly a chronic condition

Endemic areas for trachoma

- Commonly occurs in 53 countries of Africa, Asia, Central and South America

- Rare in US, but more common in crowded or impoverished living conditions, once common among children in US Native American reservations

Differential diagnosis

- Anterior lamella deficiency

- Middle lamella deficiency

- Posterior lamella deficiency

- Neuromuscular retraction

- Graves eyelid retraction

- Nonthyroid retractor inflammation (eg Sarcoidosis)

- Dorsal midbrain lesions

- Orbicularis weakness, frequently secondary to facial nerve palsy

- Mechanical effects of orbit, globe, and eyelid relation

- Congenital

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

Vertical shortening of skin due to inflammation can improve with elimination of acute inflammation.

Contraction of conjunctiva from inflammatory causes such as ocular cicatricial pemphigoid typically progresses without treatment and can result in severe corneal damage.

Contraction at level of septum can improve with observation and massage in the immediate postop period.

Retraction related to dysthyroid orbitopathy can improve with treatment, but has been demonstrated to persist in up to 40% patients (Radiology 1993; 188:115-118. QJ Med 1960; 29: 113-126).

Medical therapy

Remove inciting agents.

- Irrigate in case of burns.

- Remove allergens in case of atopy or contact dermatitis.

- Antibacterial/lid hygiene in presence of infection

- Withdraw offending agent in Stevens Johnson syndrome.

Treat underlying inflammation of skin.

- Atopy

- Topical steroids are a mainstay of therapy for atopic dermatitis.

- Recent data suggests even long durations of class III and IV steroids are well tolerated on the eyelids, although patients should still be monitored for glaucoma and cataracts. (J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 64(2):275-281)

- Rosacea

- For subtype 2, papulopustular rosacea, topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, and anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline (40 mg) appear to be effective and safe for short-term use.

- Effectiveness of treatment for erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (subtype 1) is less well documented (The Cochrance Library 2011, Issue 3)

- Icthyosis: Tazarotene 0.1% cream

Treat signs of active conjunctival inflammation.

- Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid

- Address concomitant dry eye and blepharoconjunctivitis.

- After inflammation under control, treat

- Trichiasis

- Distichiasis

- Entropion

- Retraction

- Systemic treatment with immunomodulatory agents, coordinated with rheumatologist or oncologist, after

- Baseline renal and liver function tests

- Complete blood count

- Test for glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (GGPD) deficiency

- Slowly progressive mild to moderate OCP sometimes treated with Dapsone

- Mild to moderate cases or those unresponsive to Dapsone: mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept) or Methotrexate commonly used

- Rapidly progressive moderate to severe inflammation: role for Cytoxan

- Rituximab and immunoglobulin (Ophthal 1999; 106:2136-2143)

- Steroids used in selected cases usually early in treatment (Seminars in Ophthalmology 2011;2(4-5):270-277)

- Trachoma: azithromycin and tetracycline ointment

Acute middle lamellar deficiency (within 6 months of onset) can be improved with massage with or without intralesional corticosteroid injection.

Graves upper eyelid retraction

- In the early phase of the orbitopathy, triamcinolone injected subconjunctivally has been used.

- Botulinum toxin

- Hyaluronic acid fillers (Survey of Ophthalmology 2012; 58(1)) (Curr Opin Ophthal 2011; 22:391-393)

Surgery

Surgical options are determined in part by preoperative variables:

- Lower versus upper eyelid

- Degree of retraction

- Time elapsed since surgery or trauma

- Presumed lamella(s) involved

- Relative globe prominence and/or eyelid volume deficiency

- Horizontal eyelid laxity or orbicularis weakness

- Patient preference for multiple minimally invasive procedures versus more definitive invasive procedures.

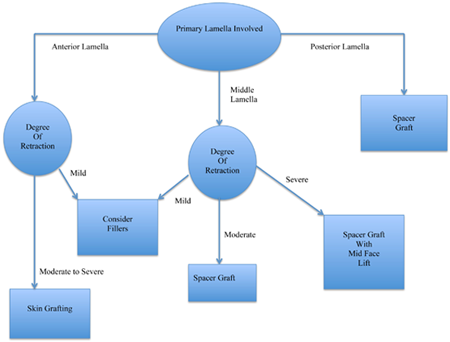

Because so many variables are involved, and there is not complete agreement on surgical approaches to retraction repair, a comprehensive algorithmic approach incorporating all variables is not possible.

A basic algorithm is presented here (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lower eyelid retraction.

Surgery for primarily anterior lamella deficiency

- Minimally invasive options

- Botulinum toxin relaxation of frontalis muscle can be temporarily helpful.

- Hyaluronic acid fillers have been used to address mild retraction. They do not lengthen the anterior lamella directly, but offer a cosmetically acceptable way to address mild retraction. (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 23(5). Orbit 2013; 32(6):362-365)

- Invasive surgical options

- Horizontal eyelid tightening, often only temporary

- Skin grafting is a very direct way to address anterior lamella shortage, and can be in form of free graft or rotational flap. Most patients achieve good eyelid position and color match, and the majority of early postoperative sequellae can be reversed by massage, steroid ointment, and silicone gel application (Ophthal Plast Reconstr 2014; 30(6))

- Spacer grafting does not address anterior lamella deficiency directly, but mid and posterior lamella grafts can be used to address mild anterior lamella shortage in a cosmetically acceptable way (Figure 3).

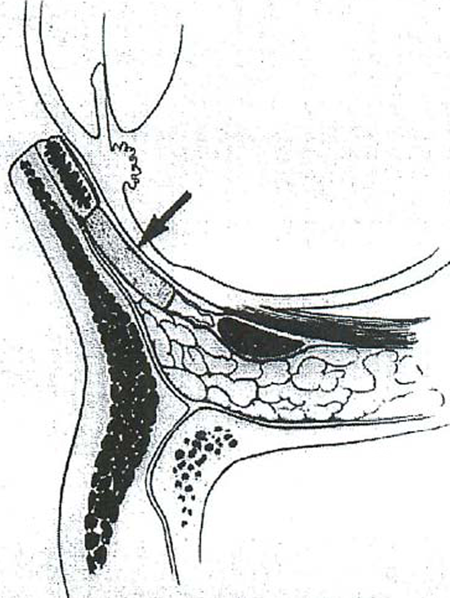

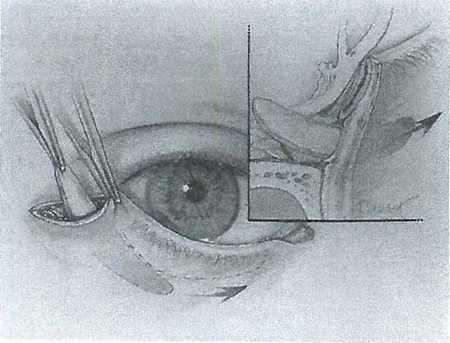

- Spacer grafts, depending on the material, can be placed “en face” (Figure 4) or “en glove” (Figure 5). (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 8: 183-195. OPRS 1992; 8(3). OPRS 2011; 27(2))

- Mid face lifting: A variety of techniques have been described for supporting the lower eyelid by addressing the mid face. (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1985; 1:229-235) (Ophthalmology 2006; 113(10)) (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 26(3))

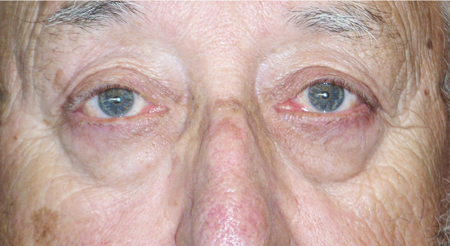

Figure 3. Top: Bilateral upper eyelid ptosis, lower rid retraction, and dry eye syndrome (rosacea). Bottom: Post-concomitant repair ptosis and retraction with human acellular dermis.

Figure 4. En face graft. (Arch Ophthal. 1990;10:1341.)

Figure 5. En glove graft. (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8(3):171.)

Surgery for posterior lamella deficiency

- Lengthening of posterior lamella with spacers, e.g., buccal mucosa, hard palate, nasal septum; see middle lamella for a more complete list.

- Horizontal tightening in presence of laxity

Surgery for middle lamella scarring

- Minimally invasive options, e.g., hyaluronic acid fillers (Ophthal Plastic Reconstr Surg 2007; 23(5))

- Division of middle lamellar scar tissue with traction suture (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 1992; 8(3))

- Spacer grafting with some rigidity to provide vertical support to tarsus of lower eyelid

- Donor sclera

- Dermis or dermis fat graft

- Auricular cartilage

- Nasal cartilage

- Hard palate mucosal grafts

- Human acellular dermis

- Procine acellulcar dermis

- Polytetrafluoroethylene

- Porous polyethylene (Figures 6 and7)

- Spacer grafting in upper eyelid not commonly needed and probably of more limited use; ideal spacer would be more flexible, e.g., temporalis fascia (Survey of Ophthalmology 2013; 58(1). Arch Ophthal 1983; 101:262-264)

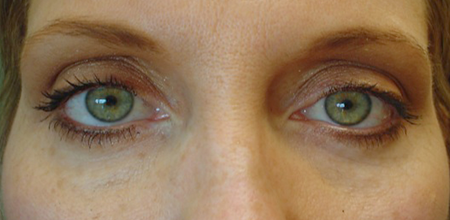

Figure 6. Top: Bilateral lower eyelid retraction secondary to esthetic surgery. Bottom: Post spacer graft, hard palate.

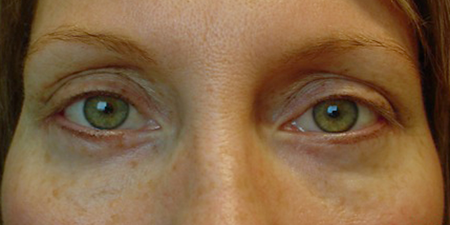

Figure 7. Top: Bilateral lower eyelid retraction secondary to esthetic surgery. Bottom: Post spacer graft porcine acellular dermal matrix.

Surgery for neuromyogenic retraction (e.g., Dysthyroid retraction, facial weakness)

- Minimally invasive

- Botulinum toxin directed to levator palpebrae superioris

- Subconjunctival triamcinalone, early in inflammatory process

- Hyaluronic acid (upper and lower) (Ophthal Plast Reconstr 2009; 25)

- Invasive surgical correction

- Upper eyelid dysthyroid retraction

- Eyelid retractors (levator palpebrae surgeries and Müller muscle) can be debilitated separately or in combination by an anterior or posterior approach.

- The muscles can be recessed, partially resected, or lengthened.

- Various spacers have been used, but improved results (in the upper eyelid) are not well documented compared to simple retractor weakening.

- Most surgeons do more aggressive surgery laterally. (Survey of Ophthalmology 2013; 58(1)).

- Upper eyelid retraction due to facial palsy: eyelid loads such as platinum or gold weights, or even hyaluronic acid (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2009; 25(1))

- Lower eyelid retraction: Retractors can be recessed (Br J Ophthalmol 2011; 95:1664-1669) or spacers can be used as previously described.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Complications of medical therapy

- Topical steroids — usually well tolerated on the eyelids, although monitor for glaucoma, cataracts. (J Am Acad Dermatol; 64(2): 275-278)

- Long term topical steroid use can also lead to skin atrophy when used at high doses

- Tetracycline products (for papulopustular rosacea)

- Tooth discoloration in the unborn fetus

- Photo sensitivity

- Gasrointestinal

- Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid treatment with immunosuppressives

- Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhibitor that suppresses T-cell lymphocytes1

- The use of tacrolimus can in some instances replace topical steroids that can have deleterious effect when used long term

- Topical tacrolimus can be used in a variety of T-cell mediated anterior segment ocular disease such as cicatrizing conjunctivitis, chronic ocular graft versus host disease, scleritis, anterior uveitis, and allergic eye disease.

- The most commonly used formulation for topical use has been 0.02-0.03% ointment used up to 3 times daily

- Most common complications are leucopenia, liver toxicity, and hypertension.

- Consider comanagement with a rheumatologist or oncologist. (Ophthalmology 2002; 109(1):11-18)

Complications of surgical treatment

- Undercorrection

- Traction sutures can help negate gravity effect during early healing.

- Completely release all cicatrix and septal scarring.

- Size skin grafts and spacer grafts adequately (allow for shrinkage).

- Overcorrection of upper eyelid retraction can be corrected with anterior levator advancement or through a posterior approach (Am J of Otolaryngol 2013; 34:550-552)

- Minimize skin graft irregularity by harvesting from ideal areas, e.g., eyelid, postauricular.

Disease-related complications

- Corneal exposure sequelae including inflammation with scarring, keratitis sicca, ulcer

- Inferior keratoconjunctivitis

- Cosmetic concerns

- Trichiasis

- Epiphora

Historical perspective

Lower eyelid retraction

- Tarsal grafts, 1965 Obear and Smith (Am J Ophthalmol. 1965; 59:1088-1090)

- Auricular grafts, 1982, Baylis HI, Rosen Neuhaus RW (Am J Ophthalmol. 1982; 93:709-712)

- Mid face lifting — 1985 Shorr N, Fallon MK (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985; 1:229-35)

- Hard palate grafts

- 1985 Siegel RF (Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1985; 76:411-414)

- 1989 Bartley GB, Kay PP (Am J. Ophthal. 1989; 107:609-612)

- 1990 Kersten RC (Arch Ophthal. 1990; 108:1339-1943)

- 1992 Cohen MS, Shorr N (Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 8(3):183-195)

- Miscellaneous autologous grafts

- 2007 Dermis fat — Korn et al. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115(4):744-751

- 2013 Autologous dermis — Yoon MN, McCulley TJ. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014; 30(6)

- 2014 Autologous fat — Le TP et al. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014; 30(6)

- Acellular cadaveric dermal matrix, introduced 1995

- Taban M, Douglas R, Li T, et al. Arch Facial Plastic Surgery. 2005; 7:38-44

- Sullivan SA, Dailey RA. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003; 19:14-24

- Rubin PA, Fay AM, Remulla HD, et al. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:2091-2097

- Aldave AJ, Maus M, Rubin PP. Facial Plastic Surg. 1999; 15:213-224

- Porcine acellular dermal collagen — first marketed in U.S., 2003

- McCord C, Nahai FR, Codner MA, et al. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2014

- Dailey RA, Douglas PM, Ahn ES. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. September 2014

- Hyaluronic acid fillers: Goldberg RA, Lee S, Jayasundera T, et al. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surgl 2007; 23:343-348

Upper eyelid retraction

In 1965 Henderson described combined weakening of Muller’s muscle posteriorly and levator aponeurosis anteriorly.

Most subsequent techniques are variations on this theme either performed anteriorly or posteriorly (Arch Ophthalmol 1965; 74:205-216) (Opthal Plast and Reconstr Surg 23(1):39-45) (Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 2011, 22:391-393).

References and additional resources

- Rosacea Triggers Survey. National Rosacea Society Web site. http://www.rosacea.org/patients/materials/triggersgraph.php

- Aldave AJ, et al. Advances in the management of lower eyelid retraction. Facial Plastic Surgery. 1999;15(3):213-224.

- Bartley GB. The differential diagnosis and classification of eyelid retraction. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:168-176.

- Bartley GB, et al. Clinical features of graves’ ophthalmopathy in an incidence cohort. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(3): 284-290.

- Bartley GB, et al. Posterior lamellar eyelid reconstruction with a hard palate mucosal graft. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:609-612.

- Baylis HI, et al. Lower eyelid retraction following blepharoplasty. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8(3):170-175.

- Baylis HI, et al. Obtaining auricular cartilage for reconstructive surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:709-712.

- Behbehani R, et al. Systemic sarcoidosis manifested as unilateral eyelid retraction. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:599-600.

- Ben Simon GJ, et al. Subperiosteal midface lift with or without a hard palate mucosal graft for correction of lower eyelid retraction. Ophthalmology. 2006; 113(10):1869-1873.

- Chang HS, et al. “En-Glove” lysis of lower eyelid retractors with alloderm and dermis-fat grafts in lower eyelid retraction surgery. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27(2):137-141.

- Cohen MS, et al. Eyelid reconstruction with hard palate mucosa grafts. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8(3):183-195.

- Collin JR, et al. Congenital eyelid retraction. Br J Ophthal. 1990;74:542-544.

- Dailey RA, et al. Porcine dermal collagen in lower eyelid retraction repair. Pubush Ahead of Print, POST AUTHOR CORRECTIONS, 5 September 2014. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg.

- Davies TF, et al. Thyroid controversy — Stimulating antibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(11):3777-3785.

- Davies TF, et al. Pathogenesis and clinical features of Graves’ ophthalmopathy (orbitopathy). 2014

- Demirci H, et al. Graded full-thickness anterior blepharotomy for correction of upper eyelid retraction not associated with thyroid eye disease. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(1):39-45.

- Eckstein AK, et al. Thyrotropin receptor autoantibodies are independent risk factors for graves’ ophthalmopathy and help to predict severity and outcome of the disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(9):3464-3470.

- Feser A, et al. Periorbital dermatitis: causes, differential diagnoses and therapy. J Detsc Dermatol Ges. 2010;8(3):159-166.

- Fezza JP. Nonsurgical treatment of cicatricial ectropion with hyaluronic acid filler. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):1009-1014.

- Goldberg RA, et al. Treatment of lower eyelid retraction by expansion of the lower eyelid with hyaluronic acid gel. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(5):343-348.

- Griffin G, et al. New insights into physical findings associated with postblepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34(7): 995-1004.

- Haeck IM, et al. Topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis and the risk of glaucoma and cataracts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(2): 275-281.

- Kazim M, et al. A review of surgical techniques to correct upper eyelid retraction associated with thyroid disease. Curr Opin Ophthal. 2011;22:391-393.

- Kersten RC, et al. Management of lower-lid retraction with hard-palate mucosa grafting. Arch Ophthal. 1990; 108:1339-1343.

- Kirzhner M, et al. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: A review of clinical features, immunopathology, differential diagnosis, and current management. Seminars in Ophthalmology. 2011;26(4-5):270-277.

- Klapper ST, et al. Congenital, paradoxical lower eyelid retraction on upgaze. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;15(2):100-105.

- Korn BS, et al. Treatment of lower eyelid malposition with dermis fat grafting. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:744-751.

- Ladoyanni E. Trigger factors, allergens and allergy testing in atopic dermatitis. In: Atopic Dermatitis — Disease Etiology and Clinical Management, Dr. Jorge Esparza-Gordillo (Ed.). InTech. 2012:213-229.

- Lamotte G, et al. Bilateral eyelid retraction, loss of vision, ophthalmoplegia: An atypical triad in anti-GQ1b syndrome. Revue Neurologique. 2014;170:469-470.

- Le TP, et al. Effect of autologous fat injection on lower eyelid position. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(6):504-507.

- Mancini R, et al. Use of hyaluronic acid gel in the management of paralytic lagophthalmos: The hyaluronic acid gel “gold weight.” Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 25(1):23-26.

- Marshak H, et al. Small incision preperiosteal midface lift for correction of lower eyelid retraction. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(3):176-181.

- McCord CD. Commentary on: New insights into physical findings associated with postblepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34(7):1005-1007.

- Noma K, et al. Bilateral upper eyelid retraction caused by topical bimatoprost therapy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28(2):33-35.

- Norris J, et al. A review of combined orbital decompression and lower eyelid recession surgery for lower eyelid retraction in thyroid orbitopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:1664-1669.

- Obear MG, et al. Tarsal grafting to elevate the lower lid margin. Amer J Ophthal. 1965;59:1088-1090.

- Olver JM, et al. Henderson’s relief of eyelid retraction revisited. Eye. 1995;9:467-471.

- Özkan SB, et al. Chemodenervation in treatment of upper eyelid retraction. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211:387-390.

- Peckinpaugh JL, et al. Large particle hyaluronic acid gel for the treatment of lower eyelid retraction associated with radiation-induced lipoatrophy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26(5):377-378.

- Rabinowitz MP, et al. Unilateral prostaglandin-associated periorbitopathy: A syndrome involving upper eyelid retraction distinguishable from the aging sunken eyelid. Publish Ahead of Print, POST AUTHOR CORRECTIONS, 12 November 2014. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg

- Rathore DS, et al. Full thickness skin grafts in periocular reconstructions: Long-term outcomes. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014; 30(6):517-520.

- Romero R, et al. Use of hyaluronic acid gel in the management of cicatricial ectropion: Results and complications. Orbit. 2013;32(6):362-365.

- Shah HA, et al. Posterior conjunctival plication to correct secondary ptosis after eyelid retraction repair in Graves disease. Am J Otolaryngol. 2013;34:550-552.

- Shams PN, et al. Upper eyelid retraction in the anophthalmic socket: Review and survey of the Australian and New Zealand society of ophthalmic plastic surgeons (ANZSOPS). Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(4):309-312.

- Shorr, N, et al. “Madame Butterfly” Procedure: Combined cheek and lateral canthal suspension procedure for post-blepharoplasty, “round eye,” and lower eyelid retraction. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;v(4):229-235.

- Shoughy SS. Topical tacrolimus in anterior segment inflammatory disorders. Eye Vis. 2017;4:7. doi:10.1186/s40662-017-0072-z

- Siegel RJ. Palatal grafts for eyelid reconstruction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1985;76(3):411-414.

- Sung MS, et al. Lower eyelid epiblepharon associated with lower eyelid retraction. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2010;24(1):4-9.

- Tariq SM, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for atopy in early childhood: A whole population birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101(5):587-593.

- van Zuuren EJ, et al. Interventions for rosacea (review). The Cochrane Library. 2011; 3:1-211.

- Vásquez LM, et al. Hyaluronic acid treatment for upper eyelid retraction after glaucoma filtering surgery. Orbit. 2011;30(1):16-17.

- Velasco Cruz AA, et al. Graves upper eyelid retraction. Surv Ophthalmol. 2013;58(1):63-76.

- Yoo DB, et al. The minimally invasive, orbicularis-sparing, lower eyelid recession for mild to moderate lower eyelid retraction with reduced orbicularis strength. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16(2):140-146.

- Yoon MK, et al. Autologous dermal grafts as posterior lamellar spacers in the management of lower eyelid retraction. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(1):64-68.