Facial Nerve Palsy

Updated May 2025

Harinderpal S. Chahal, MD; Jeffrey D. Welder, MD; Richard C. Allen, MD, PhD, FACS; Erin M. Shriver, MD, FACS; Mark Lucarelli, MD, FACS

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Bell’s palsy (idiopathic)

- Thought to encompass about 50% of all cases of facial nerve palsy. In a recent series of 2000 facial palsy patients treated at a referral facial nerve clinic, Bell’s palsy accounted for 38% of the cases.

- Idiopathic facial paralysis, believed to be associated with herpes simplex virus.

- Rapid onset < 72 hours

- More common in 15 to 45-year-olds

- More common in those with diabetes, upper respiratory ailments, immunocompromised, and pregnant patients.

- Often accompanied by a viral prodrome.

- 70%–80% recover spontaneously, though complete resolution can take months.

- Permanently altered facial function can occur in about 15%, and about7% can experience recurrence of Bell’s palsy.

- Rarely bilateral

- Treatment consists of antiviral and corticosteroid therapy, though the significance of these regimens remains unclear.

Infection

- Bacterial infections including otitis media, otitis externa, and mastoiditis can involve the facial nerve.

- Lyme disease, caused by the transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi via tick bites, causes 10% of facial nerve palsy cases.

- 25% of Lyme cases are bilateral.

- Herpes zoster virus can cause facial nerve palsy in addition to a classic painful vesicular eruption and is called Ramsay Hunt syndrome or genicular ganglionitis.

- These patients often have considerable pain and are less responsive to therapy.

- Other inciting infections include

- Diphtheria

- Enterovirus

- HIV

- Varicella

- Polio

- Mumps

- Leprosy

- Dengue fever

- Cat-scratch disease

Trauma

- Blunt or penetrating trauma to the facial nerve

- Temporal bone fracture

- Iatrogenic

- Surgery of the face, neck, ear, and/or parotid gland

- Resection of cerebellopontine angle tumors can cause Horner’s syndrome with cranial nerves V, VI, VII, and VIII palsy.

Neoplastic

- Central/nuclear lesions

- Tumors can damage the facial nerve and usually present with a more gradual onset of paralysis compared with Bell’s palsy or infection

- Brainstem/pons

- Cerebellopontine angle (such as acoustic neuroma)

- Infratemporal bone

- External auditory canal

- Parotid gland

- Peripheral nerve lesions

- Infratemporal bone tumors

- External auditory canal tumors

- Parotid gland tumors

- Facial nerve schwannoma

- Lymphoma

Inflammatory

- Sarcoidosis (Heerfordt syndrome)

- Vasculitis

Miscellaneous

- A number of other etiologies of facial nerve paralysis are documented including

- Congenital facial paralysis (Mobius syndrome)

- Autoimmune/Guillain-Barre syndrome

- Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome

- Diabetes

- Infarction

- Vascular malformations of the facial nerve

- Pontine demyelination

Epidemiology

Bell’s palsy accounts for about 50% of facial nerve palsies.

- Affects 1 in 60–70 people in a lifetime

- Peaks between the ages of 10 and 40

- Affects men and women equally

Trauma accounts for about 25% of facial nerve palsies.

Lyme disease accounts for about 10% of facial nerve palsies.

History

Observation warranted if

- Classic viral prodrome

- Rapid onset and not progressive beyond 72 hours

- Partial unilateral palsy

- Present less than 3 to 4 weeks

Imaging recommended if

- Suspicion of other diagnoses such as stroke, tumor, or head trauma with possible injury to the temporal bone.

- Multiple cranial nerves are involved

- Recurrent, same sided paralysis

- Bilateral

- Palsy not improving after 3 to 4 weeks

- Complete paralysis

- Progression beyond 72 hours (slow onset)

Clinical features

Facial nerve palsy most commonly presents as an acute onset of unilateral facial weakness or loss of facial expression including

- Loss of forehead wrinkling

- Brow ptosis

- Incomplete eyelid closure

- Drooping of the mouth with possible drooling

- There can be associated

- Pain around the jaw or behind the ear

- Headaches

- Changes in

- Taste

- Tearing

- Hearing

Common ocular signs of facial nerve palsy

- Upper eyelid retraction

- Lower eyelid paralytic ectropion and laxity with widening of the palpebral fissure

- Lagophthalmos

- Incomplete blink

- Corneal exposure keratopathy

- Punctate epitheliopathy

- Corneal pannus

- Thinning

- Corneal ulceration

Aberrant facial nerve innervation

In longstanding or recovering facial nerve palsies, most commonly Bell’s palsy, aberrant innervation can occur in 3 forms.

- Hypertonicity occurs as the affected side appears contracted at rest despite decreased dynamic function.

- Synkinesis involves regenerating axons reinnervating different muscles than those originally served, for example:

- Movements of the lower face can cause eyelid closure.

- Blinking can cause mouth twitching.

- Gustatory lacrimation (“crocodile tears”): Fibers to the sublingual and mandibular glands reinnervate the lacrimal gland causing tearing during chewing.

All 3 forms have been successfully treated with the use of botulinum toxin. Physiotherapy can be a very helpful adjunct in the management of hypertonicity and synkinesis. Therapeutic interventions such as facial exercises, neuromuscular retraining and massage aim to improve muscle tone, promote symmetry and reduce synkinesis.

Testing

Diagnosis is made based on the presence of characteristic physical exam findings as listed above.

Observation is warranted in the setting of a classic viral prodrome with rapid onset of partial unilateral palsy present for less than 3 weeks.

Although practice patterns vary, further evaluation including imaging is recommended if multiple cranial nerves are involved or the palsy

- Progresses over a period of 3 weeks

- Is complete in nature

- Has a gradual onset (>72 hours)

Current guidelines discourage routine laboratory, imaging or neurophysiological testing at the first presentation of typical Bell’s palsy.

Corneal sensation should be checked in all patients with facial nerve palsy to ensure there is no involvement of CN V, which portends a worse prognosis for exposure keratopathy and requires additional work-up to determine etiology.

The presence or absence of Bell’s phenomenon should be noted.

The extent of voluntary closure of the eyelids should be noted by having the patient gently close the eyelids and observing the extent to which the eyelids stay open.

The ocular surface should be assessed using Schirmer and fluorescein testing. Facial nerve palsy exceeding 3 months in duration can result in a loss of parasympathetic tear stimulation and altered meibomian gland morphology.

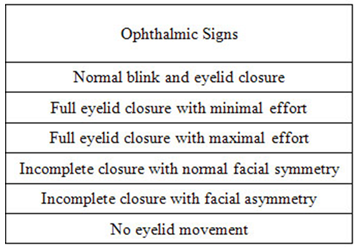

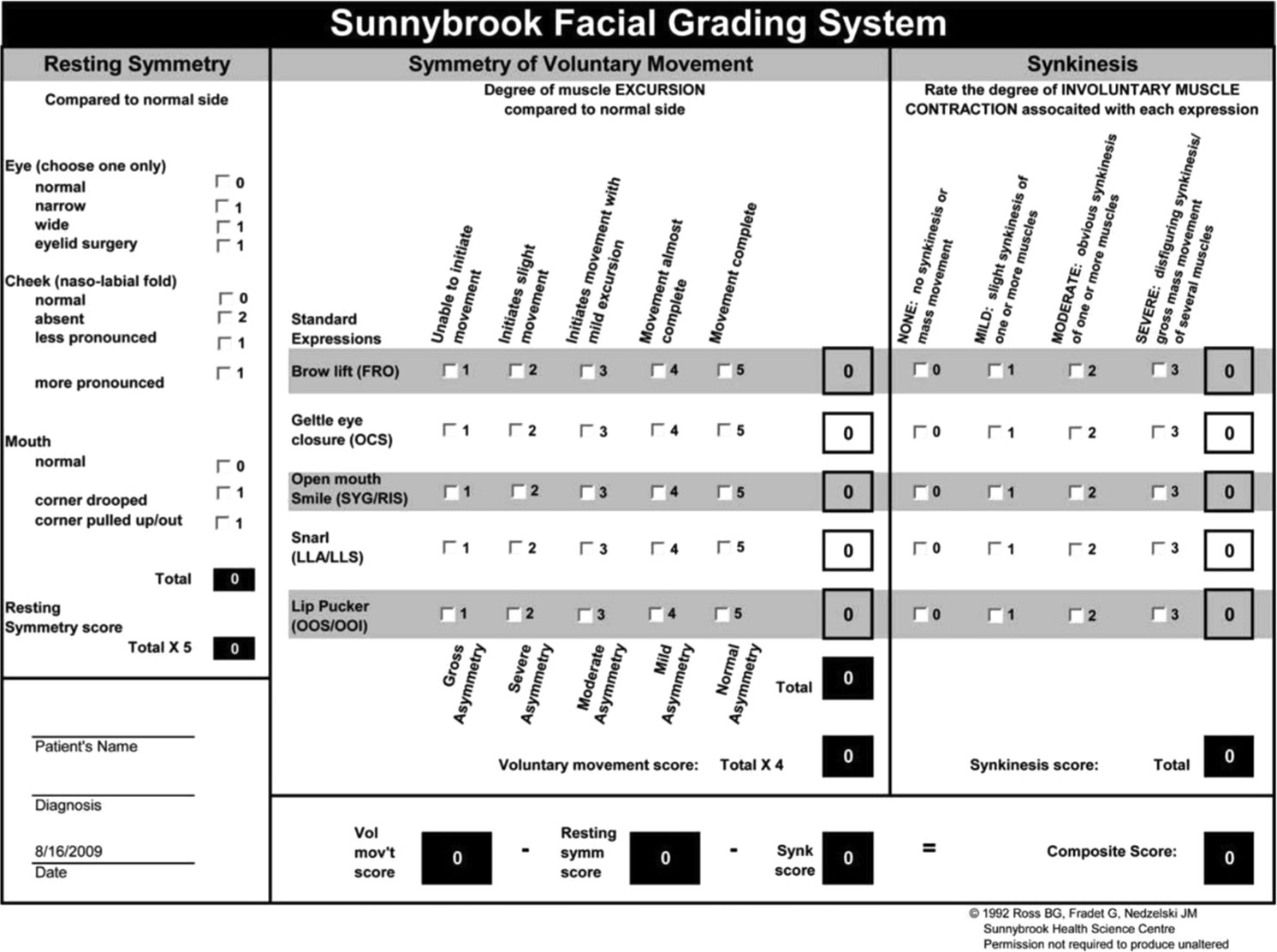

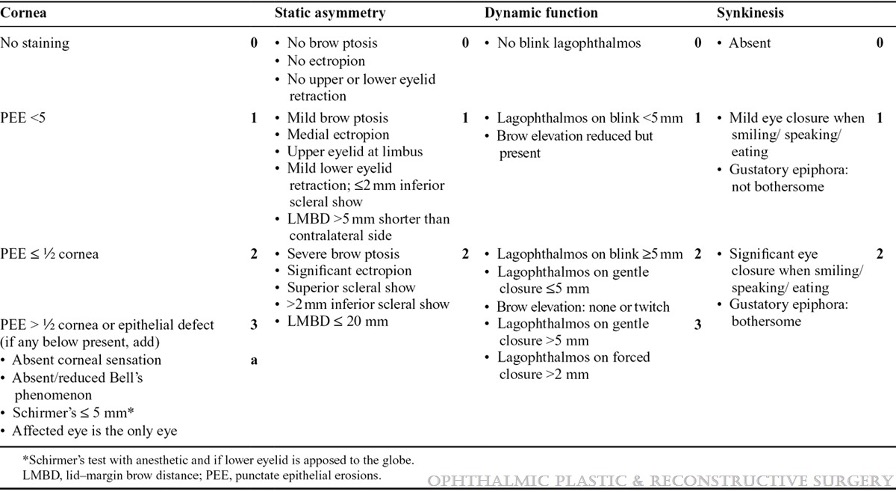

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

Grading of facial nerve palsy can be performed using one or more of the following tools:

The House-Brackman guide assesses facial symmetry at rest, voluntary movement of key regions (forehead, eye and mouth) and the presence of synkinesis or involuntary movements, providing an overall functional grade to monitor severity and recovery of facial nerve palsy.

The Sunnybrook facial grading system has been validated and uses essential information including resting symmetry, degree of voluntary excursion of facial muscles and degree of synkinesis associated with specified voluntary movement. Separate scores of resting symmetry, voluntary movement, and synkinesis are generated.

The CADS score is an ophthalmology specific tool used to assess and grade facial nerve palsy. It evaluates four key areas: cornea, static asymmetry, dynamic function and synkinesis.

Risk factors

Risk factors vary by etiology, though immunocompromised patients are likely at highest risk.

Differential diagnosis

See above for details.

- Idiopathic (Bell’s palsy) about 50%

- Trauma about 25%

- Infection

- Neoplastic

- Inflammatory

- Miscellaneous

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Medical therapy

Ophthalmology consultation is recommended in the setting of facial nerve palsy when

- Ocular symptoms are present

- There is a concern for decreased corneal sensation

- Prolonged or permanent facial nerve paralysis is expected as more intensive therapy is indicated

Conservative management can be divided into 5 broad categories.

- Aggressive lubrication of ocular surface

- Artificial tears can be used in mild cases

- Preservative-free preparations are preferred when used chronically to decrease the incidence of allergy or toxicity

- Thicker lubricating gels or ointments are useful in more severe cases and for overnight use

- Moisture retention

- Room air humidifiers

- Turning off fans

- Humidification goggles/moisture chambers

- Taping eyelids shut.

- Obstruction of tear outflow

- Punctal plugs

- Thermal punctual cautery

- Improvement of tear film quality

- Use of warm compresses

- Lipid-enhanced artificial tears

- Oral omega 3 supplementation (fish and flaxseed oil)

- Doxycycline

- Autologous serum tears

- Lipiflow or similar procedures

- Contact lenses

- Bandage soft contact lenses can be used to protect the ocular surface. Use of these lenses require antibiotic prophylaxis, strict patient compliance with instructions and frequent follow up to prevent infections.

- Scleral contact lenses are especially beneficial in patients with CN V and CN VII palsies and can provide an excellent long-term solution for corneal exposure.

- They can also be customized to the patient’s corneal and refractive needs.

Surgery

Temporary procedural lid closure

- Temporary eyelid weights

- The upper eyelid can be lowered using adhesive stick-on weights with or without a splint, resulting in immediate eyelid closure, for example:

- Blinkeze external lid weights

- Stamler lid splint

- Temporary eyelid closure applique

- Botulinum toxin

- Protective ptosis can be induced with 5–15 units injected into the levator muscle.

- Complications of toxin injection include diplopia which can last up to 9 months after injection.

- Hyaluronic acid gel

- Can be injected to mechanically lower the upper eyelid

- Reversible with hyaluronidase

- Temporary tarsorrhaphy

- Cyanoacrylate glue or Dermabond to eyelashes

- Generally lasts 2 weeks

- Can be taken down by cutting the eyelashes after anesthesia with 4% lidocaine gel

- Temporary suture tarsorrhaphy

- Absorbable or nonabsorbable suture can be used.

- Bolsters can be used to prevent the suture from pulling through the eyelids.

- A releasable technique can allow for intermittent opening of the eyelids for corneal examination.

Permanent lid closure/lid loading

- Gold or platinum weight placement

- Effective in reducing upper lid retraction, improving blink kinetics and reducing lagophthalmos.

- Beware metal allergies; allergic complications seen in approximately 5%–7% of patients with gold weight placement

- Practice patterns vary, but supratarsal may be favorable compared with pretarsal placement in terms of visibility and possibly exposure. Sizing may be more difficult with supratarsal placement. With supratarsal placement some experts recommend concomitant recession of the levator aponeurosis.

- Lid load with gold weight showed more favorable effect on eyelid blink kinetics than surgical cerclage of the upper lid with autologous temporalis fascia.

- Lateral tarsorrhaphy

- Most common form of permanent lid closure. Involves closing the temporal palpebral fissure

- Effective, but can limit peripheral vision and be cosmetically objectionable

- Medial tarsorrhaphy

- Improves medial descent when orbicularis tone is poor but is less effective than a lateral tarsorrhaphy.

- Pillar tarsorrhaphy

- Involves connecting the upper and lower eyelid on either side of the pupil which can provide complete closure while still allowing for examination of the cornea.

- Lateral tarsoconjunctival onlay flap. Similar to Hughes tarsoconjuntival advancement flap with a small flap of lateral tarsus and conjunctiva advanced into the lateral paralytic lower lid.

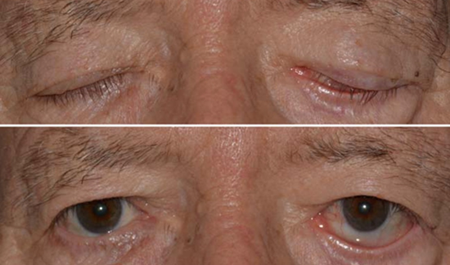

Figure 1. External photography demonstrating left lower eyelid retraction with inferior scleral show. There is left lagophthalmos present during eyelid closure.

Midface lift

- In addition to orbicularis paralysis, the concomitant paralytic ptosis of the malar-cheek soft tissues is responsible for progressive weakening of the ligamentous structures (such as medial and lateral canthal ligaments, and orbitomalar ligament), resulting in a lack of support for the lower eyelid.

- Midface lifting consisting of suborbicularis fat repositioning, lateral orbicularis orbital suspension, and lateral canthopexy, has been shown to be effective in static lower eyelid malposition correction after chronic nerve palsy.

Temporalis muscle transfer

- A facial reanimation technique used in patients with incomplete nerve palsy to recreate a symmetric smile.

- The insertion of the temporalis muscle is removed from its insertion on the mandible and attached to the orbicularis oris muscle

Corneal Neurotization

Disease-related complications

- Progressive keratopathy leading to ulceration/blindness

- Wasting of facial muscles with resultant facial asymmetry

Historical perspective

- Thought to have been first described by Persian physician Muhammad al-Razi (865–925)

- Future therapy

- Direct eyelid reanimation: Reinnervation techniques include the use of

- Contralateral supratrochlear

- Supraorbital nerves

- Leg sural nerve transfer

Videos

- Permanent Punctal Occlusion

- Glue Tarsorrhaphy

- Temporary Bolster Tarsorrhaphy

- Lateral Tarsorrhaphy

- Medial Tarsorrhaphy

- Pillar Tarsorrhaphy

- Direct Browplasty for Paralytic Brow Ptosis

- Gold Weight Insertion

- Hard Palate Graft for Lower Eyelid Retraction

- Drill Hole Midface Lift

- Enduragen Graft to Lower Eyelid

References and additional resources

- Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell’s palsy. Bmj 2004;329:553-7.

- Victor M, Martin J. Disorders of the cranial nerves. In: Isselbacher KJ, et al., eds. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 13th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 1994:2347-52.

- Peitersen E. The natural history of Bell’s palsy. The American journal of otology 1982;4:107-11.

- Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s palsy: diagnosis and management. American family physician 2007;76:997-1002.

- Clark JR, Carlson RD, Sasaki CT, Pachner AR, Steere AC. Facial paralysis in Lyme disease. The Laryngoscope 1985;95:1341-5.

- Dickins JR, Smith JT, Graham SS. Herpes zoster oticus: treatment with intravenous acyclovir. The Laryngoscope 1988;98:776-9.

- Lee V, Currie Z, Collin JR. Ophthalmic management of facial nerve palsy. Eye 2004;18:1225-34.

- Rahman I, Sadiq SA. Ophthalmic management of facial nerve palsy: a review. Survey of ophthalmology 2007;52:121-44.

- Prescott CA. Idiopathic facial nerve palsy (the effect of treatment with steroids). The Journal of laryngology and otology 1988;102:403-7.

- Boerner M, Seiff S. Etiology and management of facial palsy. Current opinion in ophthalmology 1994;5:61-6.

- Borodic G, Bartley M, Slattery W, et al. Botulinum toxin for aberrant facial nerve regeneration: double-blind, placebo-controlled trial using subjective endpoints. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2005;116:36-43.

- Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2013;149:S1-27.

- Call CB, Wise RJ, Hansen MR, Carter KD, Allen RC. In vivo examination of meibomian gland morphology in patients with facial nerve palsy using infrared meibography. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery 2012;28:396-400.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 1985;93:146-7.

- Robinson C, Tantri A, Shriver E, Oetting T. Temporary eyelid closure applique. Archives of ophthalmology 2006;124:546-9.

- Kirkness CM, Adams GG, Dilly PN, Lee JP. Botulinum toxin A-induced protective ptosis in corneal disease. Ophthalmology 1988;95:473-80.

- Ellis MF, Daniell M. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) when used to produce a protective ptosis. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 2001;29:394-9.

- Mancini R, Taban M, Lowinger A, et al. Use of hyaluronic Acid gel in the management of paralytic lagophthalmos: the hyaluronic Acid gel “gold weight”. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery 2009;25:23-6.

- Trivedi D, McCalla M, Squires Z, Parulekar M. Use of cyanoacrylate glue for temporary tarsorrhaphy in children. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery 2014;30:60-3.

- Donnenfeld ED, Perry HD, Nelson DB. Cyanoacrylate temporary tarsorrhaphy in the management of corneal epithelial defects. Ophthalmic surgery 1991;22:591-3.

- Leahey AB, Gottsch JD, Stark WJ. Clinical experience with N-butyl cyanoacrylate (Nexacryl) tissue adhesive. Ophthalmology 1993;100:173-80.

- Rapoza PA, Harrison DA, Bussa JJ, Prestowitz WF, Dortzbach RK. Temporary sutured tube-tarsorrhaphy: reversible eyelid closure technique. Ophthalmic surgery 1993;24:328-30.

- Shoham A, Lifshitz T. A new method of temporary tarsorrhaphy. Eye 2000;14 Pt 5:786-7.

- Ghadiali L, Piotti K, Lelli G. Histopathology after temporary tarsorrhaphy. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2013;54:5351-.

- Elner VM, Demirci H, Morton AD, Elner SG, Hassan AS. Transcaruncular medial canthal ligament plication for repair of lower eyelid malposition. Archives of ophthalmology 2007;125:374-9.

- Tanenbaum M, Gossman MD, Bergin DJ, et al. The tarsal pillar technique for narrowing and maintenance of the interpalpebral fissure. Ophthalmic surgery 1992;23:418-25.

- Steiner GC, Gossman MD, Tanenbaum M. Modified tarsal pillar tarsorrhaphy. American journal of ophthalmology 1993;116:103-4.

- Graziani C, Panico C, Botti G, Collin RJ. Subperiosteal midface lift: its role in static lower eyelid reconstruction after chronic facial nerve palsy. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2011;30:140-4.

- Aum JH, Kang DH, Oh SA, Gu JH. Orthodromic transfer of the temporalis muscle in incomplete facial nerve palsy. Archives of plastic surgery 2013;40:348-52.

- Gantz BJ, Rubinstein JT, Gidley P, Woodworth GG. Surgical management of Bell’s palsy. The Laryngoscope 1999;109:1177-88.

- Sajadi MM, Sajadi MR, Tabatabaie SM. The history of facial palsy and spasm: Hippocrates to Razi. Neurology 2011;77:174-8.

- Allevi F, Fogagnolo P, Rossetti L, Biglioli F. Eyelid reanimation, neurotisation, and transplantation of the cornea in a patient with facial palsy. BMJ case reports 2014;2014.

- Terzis JK, Dryer MM, Bodner BI. Corneal neurotization: a novel solution to neurotrophic keratopathy. Plastic and reconstructive surgery 2009;123:112-20.

- Ross BG, Fradet G, Nedzelski JM. Development of a sensitive clinical facial grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996; 114:380–386.

- Hohman MH, Hadlock TA. Etiology, diagnosis, and management of facial palsy: 2000 patients at a facial nerve center. Laryngoscope 2014;124:E283–9.

- Wambier SP, Garcia DM, Cruz AA, Messias A. Spontaneous Blinking Kinetics on Paralytic Lagophthalmos After Lid Load with Gold Weight or Autogenous Temporalis Fascia Sling. Curr Eye Res. 2016 Apr;41(4):433-40.

- Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical practice guideline Bell’s palsy. Executive Summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;149: 656-663.

- Li Y, Li Z, Yan C, Hui L. The effect of total facial nerve decompression in preventing further recurrence of idiopathic recurrent facial palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015 May;272(5):1087-90.

- Allen RC. Controversies in periocular reconstruction for facial nerve palsy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep;29(5):423-427.

- van Landingham SW, Diels J, Lucarelli MJ. Physical therapy for facial nerve palsy: applications for the physician. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018 Sep;29(5):469-475.

- MacIntosh PW, Fay AM. Update on the ophthalmic management of facial paralysis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019 Jan – Feb;64(1):79-89.

- Gronseth GS, Paduga R. American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2012;79:2209–13.

- Eviston TJ, Croxson GR, Kennedy PG, Hadlock T, Krishnan AV.Bell’s palsy: aetiology, clinical features and multidisciplinary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;86(12):1356-61.

- Tao JP, Vemuri S, Patel AD, Compton C, Nunery WR. Lateral tarsoconjunctival onlay flap lower eyelid suspension in facial nerve paresis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Jul-Aug;30(4):342-5.

- DeBord K, Ding P, Harrington M, Duggal R, Genther DJ, Ciolek PJ, Byrne PJ. Clinical application of physical therapy in facial paralysis treatment: A review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2023 Dec;87:217-223.

- Khan AJ, Szczepura A, Palmer S, Bark C, Neville C, Thomson D, Martin H, Nduka C. Physical therapy for facial nerve paralysis (Bell’s palsy): An updated and extended systematic review of the evidence for facial exercise therapy. Clin Rehabil. 2022 Nov;36(11):1424-1449.

Financial disclosures

Reviewers

Dianne Schlachter – Consultant & Speaker, Amgen