Floppy Eyelid Syndrome

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Floppy eyelid syndrome (FES) is a mechanical eyelid abnormality in patients who tend to sleep prone or on the affected side, with resultant stretching of the eyelid.

Progressive stretching leads to upper eyelid eversion at night and mechanical irritation of exposed conjunctiva especially during sleep, causing chronic papillary conjunctivitis.

FES is on a spectrum of lax eyelid conditions that vary in symptoms and severity (Fowler, OPRS 2010).

Histopathologic studies demonstrate decreased tarsal elastin and the tarsus becomes rubbery and lax (Ezra, Surv Ophthalmol 2010; 55:35).

- Coexisting elastin changes in the uvula have been noted (Series, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004), pointing to a possible systemic fibroblastic anomaly.

- Reduced innervation of pharyngeal musculature has been reported in obstructive sleep apnea (De Bellis, Sleep Breath 2012) but not in the eyelid.

Unilateral cases are often associated with unilateral sleeping preference, favoring mechanical mechanisms as significant contributing factors in upper lid laxity.

The sleep pattern is associated with obstructive sleep apnea. Daytime somnolence and morning headaches suggest obstructive sleep apnea.

A separate disease pattern of obstructive sleep apnea in children is associated with tonsil hypertrophy or craniofacial abnormalities.

- No data is available regarding prevalence of FES or histopathologic evidence of tarsal abnormalities in these children.

Epidemiology

- Slightly more prevalent in men than women

- Most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged patients (35–55 years)

- Usually seen in obese patients

- A study of 118 found that 85% with FES also had obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and 77% of those with OSA had FES or eyelid hyperlaxity (Muniesa, Br J Ophthalmol 2013).

- In a prospective examination of 127 patients with OSA, 25% had FES, the association increasing with increased severity of OSA (Chambe, J Sleep Res 2012).

- In another screening study of 44 patients with obstructive sleep apnea, only one patient had floppy eyelid (Karger, Ophthalmology 2006).

- Screening for floppy eyelid among sleep apnea patients is recommended by some, but the yield is not high (McNab, Sleep Med Rev 2007).

- Screening for obstructive sleep apnea among floppy eyelid patients is also recommended by some, and the yield is potentially higher (85% in the BJO study above).

History

- Patients most commonly complain about conjunctival injection and foreign body sensation.

- Many have a chief complaint of ptosis and some are specifically aware of lash ptosis, a sign of severe lid laxity — “I’m looking through my eyelashes.”

- Inquire about sleep habits and signs of sleep apnea; many are already using positive pressure ventilation devices at night.

- Does the patient sleep on their side or face down in pillow?

- Are there frequent episodes of waking up during the night?

- Inquire about coexisting glaucoma.

- In one study, 23% of obstructive sleep apnea patients with FES had glaucoma, while only 5% with OSA alone had glaucoma (Muniesa, J Glaucoma 2014).

- Ropy, mucoid discharge that is usually worse in the morning

- There might be visual complaints related to keratopathy.

- If the patient is not obese, inquire about bariatric surgery.

Clinical features

Hypertension and congestive heart failure are frequently sequelae of chronic obstructive sleep apnea.

- Referral to a pulmonologist can be made, concurrent with suggestions for correction of the lid abnormality.

Obesity and its myriad metabolic sequelae are highlighted by the presentation of FES.

There is an association with keratoconus (Ezra, Ophthalmology 2010), which might be from chronic eye rubbing as well as obesity and lid laxity (Pihlblad, Cornea 2013).

Testing

- The diagnosis is established on clinical grounds.

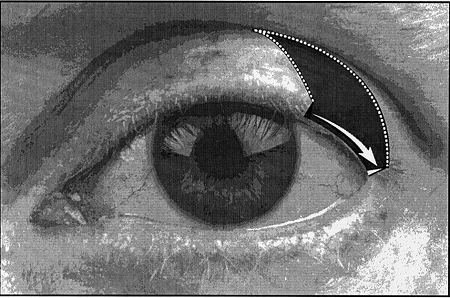

- The critical finding is an upper eyelid that is markedly lax, easily pulled toward the brow (Figure 1).

- The upper eyelid usually easily everted and has a rubbery consistency.

- There is frequently lower eyelid horizontal laxity as well.

- Severe upper lid laxity causes lash ptosis and loss of parallelism.

- There are signs of chronic irritation and inflammation at multiple locations on and around the eye.

- Lash debris (scurf)

- Tear break-up time less than 10 seconds, indicating tear instability

- Superior tarsal conjunctival injection

- Conjunctival papillary reaction from chronic irritation

- Punctate fluorescein staining of superior cornea and conjunctiva

- Conjunctival scrapings reveal predominance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with variable amounts of eosinophils and lymphocytes.

- Atrophic, soft, and rubbery tarsal plate that can be folded on itself

- Stringy mucoid conjunctival discharge

- Eyelid ptosis

- Can be confused with involutional changes if upper lid laxity is not recognized.

- Brow ptosis

- Dermatochalasis

- Lacrimal gland prolapse

- Meibomian gland dysfunction

Figure 1. Floppy eyelid syndrome.

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

While addressing the eyelid, metabolic problems should be addressed.

- In obstructive sleep apnea, the pharynx easily collapses during inspiration, resulting in loud snoring and eventual apnea, causing the patient to awaken.

- Difficulty achieving and maintaining a deep restorative phase of sleep leads to daytime somnolence and fatigue.

- Patients with obstructive sleep apnea are at increased risk of systemic and pulmonary hypertension, congestive heart failure, and cardiac arrhythmias.

- Obesity contributes to airway obstruction and disrupted sleep.

Risk factors

Obesity is the most significant risk factor; the problem is mechanical.

The sleep pattern is almost always responsible, except for rare cases with excessive lid rubbing.

Differential diagnosis

- Involutional ptosis

- Dry eye

- Involutional ectropion

- Meibomian gland dysfunction

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

The natural history is for the laxity to worsen and for the ocular surface irritation to persist and worsen.

Corneal erosion can result from chronic mechanical abrasion and can lead to scarring.

Medical therapy

Ocular lubrication at night can protect the eye from exposure.

Meibomian gland dysfunction can be treated with tetracycline and other measures.

Blepharitis can be treated with steroid/antibiotic ointment.

Eyelids can be taped and eye shield can be worn while asleep.

Sleep apnea can be treated with positive pressure ventilation.

Surgery

There are important differences between horizontal tightening of the upper versus the lower eyelid.

- The lower lid is static, whereas the upper lid is dynamic.

- Raising the upper lid accentuates lid margin irregularities and notching after wedge excision on the upper lid.

- In lower lid wedge excision, palpebral conjunctival disruption is mostly away from the cornea, whereas upper lid wedge excision disrupts the palpebral conjunctiva in direct contact with the cornea.

- The lower lid tarsus has a constant height of 4 mm across the horizontal span, whereas the upper lid tarsus has a variable height of 3–10 mm.

- The most vulnerable area of the lower lid is medial at the tear drainage system, whereas the vulnerable area of the upper lid is lateral where the lacrimal gland ductules emerge.

- The “dog ear” created by a large wedge excision in the lower lid will extend below the lid margin and can be blended into the skin tension lines, whereas the same excision in the upper lid creates a vertically oriented scar that runs perpendicular to and in the direction of the lid crease (Figure 2).

- A lid crease incision can be made to redistribute skin after an upper lid wedge excision.

- Horizontally tightening the lower lid does not significantly change its position because it is a straight line, whereas horizontally tightening the upper lid can induce a ptosis because it is an arc.

- Shortening the circumference reduces the radius.

- The arc length of excised tissue in tightening the upper lid for FES is commonly greater than the length of excised tissue in tightening the lower lid for ectropion.

Lower lid laxity is frequently repaired at the same time as upper lid laxity in FES.

- The two incision sites should ideally be adequately separated, for example, by performing a wedge excision in the upper lid and lateral tarsal strip procedure in the lower lid.

Pentagonal wedge resection (Figure 3) at the lateral third of the upper eyelid is a reasonable approach to tightening the upper lid.

The wedge excision can be performed in the medial third of the lid.

Lateral tarsal strip repair of the upper lid can be performed, but care must be taken to avoid trauma to lacrimal gland ductules.

A temporally placed back-tapered wedge resection and advancement flap can be performed to create a wound that is more nearly parallel to the eyelid crease, potentially camouflaging it (Perlman, OPRS 2002).

Figure 2. 2–3-mm incisions perpendicular to the lateral canthal angle and curvilinear lid crease incision.

Figure 3. Pentagonal excision of posterior lamella.

Other management considerations

There might be a need for concurrent repair of ptosis, dermatochalasis, or lacrimal gland prolapse.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

Once the mechanical laxity has been adequately corrected, the inflammation should improve.

Further tightening might be needed until the problem is adequately corrected.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Complications can occur along the surgical wound with a notch at the lid margin or irregularity along the palpebral conjunctiva causing disruption of the corneal epithelium.

The rubbery eyelid is difficult to suture with perfect tissue apposition.

Eyelid height or contour might be unacceptable and require revision.

Paradoxically, horizontal tightening of the upper eyelid can result in elevation of the lid margin, typically 1.5–3.5 mm (Figure 4) (Mills, Ophthalmology 2007).

Lash ptosis can persist despite adequate lid tightening.

Figure 4. Elevation of lid margin.

Disease-related complications

Complications from the disease occur mostly at the corneal surface.

Eye rubbing postoperatively and continued sleep disturbance can lead to disruption of the surgical wound and continued ocular irritation.

Historical perspective

FES was first described in 1981 by Culbertson and Ostler (AJO 1981; 92:568).

References and additional resources

- Chambe J, Laib S, Hubbard J, et al: Floppy eyelid syndrome is associated with obstructive sleep apnea: a prospective study on 127 patients. J Sleep Res 2012; 21:308.

- Culbertson WW, Ostler HB: The floppy eyelid syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1981; 92:568.

- DeBellis M et al. Immunohistochemical and histomorphometric study of human uvula innervation: a comparative analysis of non-snorers versus apneic snorers. Sleep Breath 2012; 16:1033-40.

- Ezra DG, Beaconsfield M, Sira M, et al. The associations of floppy eyelid syndrome: a case control study. Ophthalmology 2010;117:831.

- Ezra DG, Beaconsfield M, Collin R. Floppy eyelid syndrome: stretching the limits. Surv Ophthalmol 2010; 55:35.

- Fowler AM, Dutton JJ. Floppy eyelid syndrome as a subset of lax eyelid conditions: relationships and clinical relevance (an ASOPRS thesis). Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;26:195.

- Karger RA, White WA, Park WC, et al. Prevalence of floppy eyelid syndrome in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Ophthalmology 2006;113:1669.

- McNab AA. The eye and sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev 2007; 11:269-76.

- Mills DM, Meyer DR, Harrison AR: Floppy eyelid syndrome: quantifying the effect of horizontal tightening on upper eyelid position. Ophthalmology 2007; 114:1932.

- Muniesa MJ, Huerva V, Sánchez-de-la-Torre M, et al: The relationship between floppy eyelid syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea. Br J Ophthalmol 2013; 97:1387.

- Muniesa M, Sanchez-de-la-Torre M, Huerva V, Lumbierres M, Barbe F: Floppy eyelid syndrome as an indicator of the presence of glaucoma in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Glaucoma 2014; 23:e81.

- Perlman LM, Sires BS: Floppy eyelid syndrome: A modified surgical technique. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18:370.

- Pihlblad MS, Schaefer DP: Eyelid laxity, obesity and obstructive sleep apnea in keratoconus. Cornea 2013; 32:1232.

- Series F et al. Influence of weight and sleep apnea status on immunological and structural features of the uvula. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:1114-9.