Frontalis Suspension

Updated August 2024

Michael A. Burnstine, MD, FACS; Edward J. Wladis, MD

Frontalis suspension techniques are reserved for patients with profound ptosis and poor eyelid opening/levator excursion. It is the procedure of choice to prevent amblyopia in severe unilateral and bilateral ptosis patients where the eyelid is covering the pupillary axis, whereas cases of less severe ptosis or those associated with better levator function may be amenable to repair via other techniques.

Primary and secondary goals of procedure

- The primary goal of frontalis suspension techniques in ptosis management is to improve visual function by elevating the eyelid.

- A secondary goal is to improve facial aesthetics and symmetry.

Indications and contraindications

Indications

- Static ptosis with levator excursion less than 4 mm

- Congenital myopathic ptosis (levator maldevelopment) with high risk of occlusive amblyopia

- Blepharophimosis ptosis syndrome

- Marcus Gunn jaw-winking

- Occurs in 5% of congenital ptosis cases

- Congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles

- Double elevator palsy

- Myogenic ptosis

- Progressive external ophthalmoplegia with levator excursion less than 4 mm and reasonable Bell’s phenomenon (Lane and Collin 1987)

- Kearns Sayre syndrome (heart block, retinitis pigmentosa, abnormal retinal pigmentation)

- Oculopharyngeal dystrophy

- French-Canadian descent

- Myotonic dystrophy

- Stephens syndrome

- Congenital disorders (rare association)

- Abetalipoproteinemia

- Refsum disease

- Extraocular muscle fibrosis syndrome

- Moebius syndrome

- Progressive supranuclear palsy

- Endocrine exophthalmos

- Myasthenia gravis, occasionally, after maximal medical therapy

- Muscular dystrophy

- Traumatic ptosis with levator excursion less than 4mm

- Apraxia of eyelid opening (DeGroot, OPRS, 2000)

Contraindications

- Absolute: other ptosis types that require different management (Frueh 1980)

- Pseudoptosis

- Dermatochalasis

- Enophthalmos

- Hypotropia

- Globe malposition

- Small eye: phthisis bulbi, micro-ophthalmos, anophthalmos, enophthalmos and postenucleation

- Mechanical ptosis

- Excessive lid weight

- Eyelid tumor

- Restrictive ptosis due to conjunctival scarring

- Aponeurotic ptosis

- Myopathic ptosis with levator excursion greater than 4 mm

- Neurogenic ptosis

- Aberrant third nerve regeneration

- Myasthenia gravis amenable to medical therapy

- Horners syndrome

- Ophthalmic migraine

- Multiple sclerosis

- Weakness of the frontalis muscle

- Relative

- Neurogenic ptosis due to third nerve palsy

- Poor Bells phenomenon with risk of corneal exposure keratopathy

- Paralytic strabismus with high risk for postoperative diplopia

- Progressive external ophthalmoplegia with poor Bells phenomenon

- Risks of corneal exposure keratopathy due to ocular dysmotility

- Muscular dystrophy that is progressive and the cornea is at risk

Preprocedure evaluation

History of ptosis

- Age of onset

- Progressive or static

- Variable

- Family history of ptosis

- Old photo evaluation for corroboration of history and time of disease onset

Clinical examination/preoperative assessment

- Complete eye exam with critical key components:

- Vision

- Pupil size and reflexes

- Extraocular motility

- Slit lamp examination looking for exposure keratopathy

- Funduscopic examination for retinal pigmentary changes

- Schirmer testing for dry eye

- Thorough eyelid evaluation

- Palpebral fissure (PF)

- Palpebral fissure on downgaze (dPF)

- Increased in static myopathic ptosis (congenital)

- Margin reflex distance 1 (MRD1)

- Margin crease distance (MCD)

- Margin fold distance (MFD)

- Levator excursion (LE) = levator function

- Lagophthalmos

- Presence of Bells phenomenon (absent, poor, fair, good)

- Synkinesis

- Aberrant innervation syndrome: Marin-Amat (III-VII miswiring)

- Marcus Gunn jaw-winking (III-V miswiring)

- Duane syndrome (change in PF in horizontal gaze (III-VI miswiring)

- Intact frontalis function is essential to the success of the procedure

Alternatives to procedure

- Eyelid crutch to prop open eyelid, worn on glasses frame

- Supramaximal blepharoplasty (Burnstine and Putterman 1999)

- Designed to remove the maximal amount of skin to allow for eyelid closure (when the brow is relaxed) and pupil clearance (when the eyebrow is elevated)

- Ideal for patients with the relative contraindications above, particularly those patients with a poor Bells phenomenon and decreased extraocular motility whose corneas are at risk

- Other ptosis repair techniques are generally used for patient with fair to normal levator function

Techniques

Suspension techniques

- Two strips of fascia lata (Magnus 1936)

- Rhomboid technique (Tillett and Tillett 1965)

- Double rhomboid technique

- Crawford pentagon operation (Crawford 1956), modified Wright operation (Wright 1922)

- Fox procedure, trapezoid-pentagon

- Transconjunctival frontalis suspension

Materials

Autogenous fascia lata (Figures 1 – 5)

- Recommended by Wright in 1922 and modified by Crawford (1956) and Fox (1957)

- Long considered the gold standard in frontalis suspension ptosis management

- Pros

- Material from self

- Biointegrated into body

- Low complication and recurrence rate (Wasserman et al, 2001)

- Cons

- Separate surgical harvest site with risk of infection and muscle prolapse

- Early pain on walking (67%), limping (38%), wound pain (57%), and cosmesis concerns on final wound healing (38%) (Wheatcroft et al, 1997)

- Patient must be at least 5 years old to have enough tissue to harvest

- Postoperative donor-site scarring

- Difficult to revise due to postoperative scarring

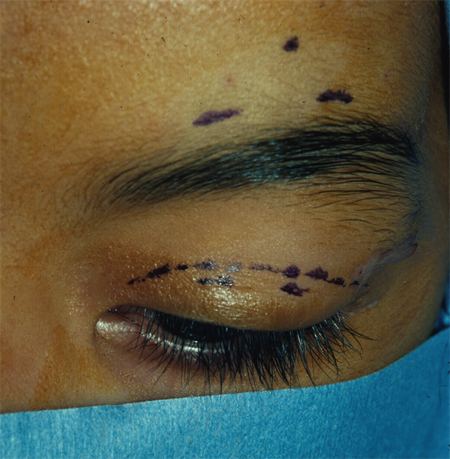

Figure 1. Frontalis suspension with autogenous fascia lata, closed technique. Surgical markings in eyelid and above brow. Courtesy Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS.

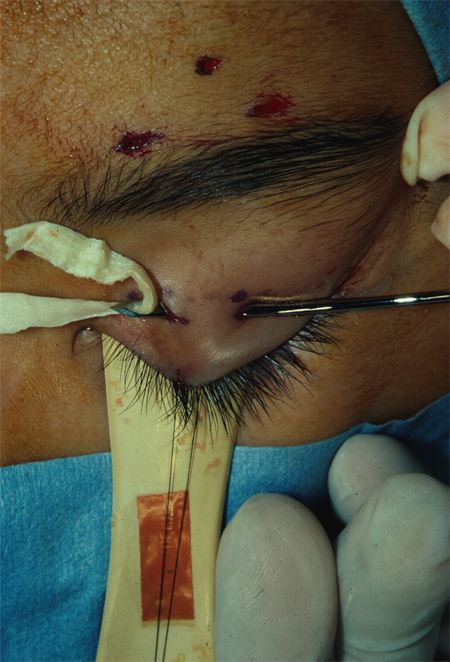

Figure 2. Frontalis suspension with autogenous fascia lata, closed technique. A Wright fascial needle is used to pass the fascial lata strip through the lid. Courtesy Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS.

Figure 3. Frontalis suspension with autogenous fascia lata, closed technique. The fascial lata strip is passed through the brow in a pentagonal pattern and tied through the central brow incision. Courtesy Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS.

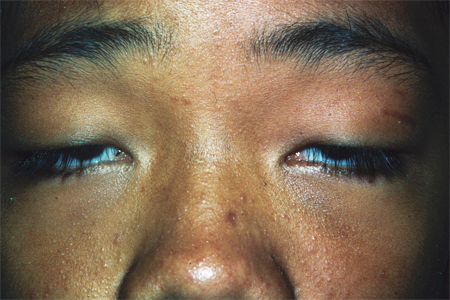

Figure 4. Preoperative photograph from bilateral frontalis suspension with autogenous fascia lata. Courtesy Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS.

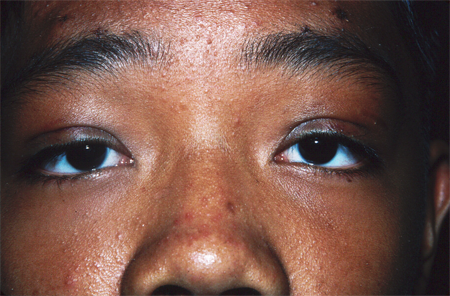

Figure 5. Postoperative photograph from bilateral frontalis suspension with autogenous fascia lata. Courtesy Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS.

Nonautogenous lysophilized/banked fascia lata (Tutoplast)

- Pros

- Biointegration

- No need for second surgical site

- Cons

- Reported recurrence rate from 8% (Broughton et al, 1982) to 18% (Wasserman et al, 2001)

Silicone rod (Figures 6, 7)

- Tillet and Tillet (1966) first described its use in frontalis suspension

- Pros

- Elastic

- Ease of adjustment and removal

- No second-site harvest

- Cons

- Early revision 4% (Morris et al, 2008)

- Complications:

- Infection (Morris et al, 2008) (Davies et al, 2013)

- Extrusion (Carter et al, 1995)

- Granuloma formation (Rizvi et al, 2014)

![]()

Figure 6. Frontalis suspension with silicone sling, open technique. Silicone sling is fixated to the tarsus. Courtesy Richard C. Allen, MD, PhD, FACS.

![]()

Figure 7. Frontalis suspension with silicone sling, open technique. Sling is passed superiorly in the postseptal plane through the suprabrow incision. Courtesy Richard C. Allen, MD, PhD, FACS.

Mersilene mesh (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ)

- Pros

- Provides a scaffold for fibrovascular ingrowth

- Becomes biointegrated

- Comparable outcomes to autogenous fascia lata (Salour et al., 2008)

- Cons

- High complication rate of 20% (extrusion, granuloma, and infection) (Mehta et al, 2004)

Supramid (nylon polyfilament cable suture)

- Pros

- Quick and easy (Betharia, 1985)

- Cons

- Sling fails over time (Liu, 1999) (Tannenbaum et al, 2014)

- Suggested as temporizing measure

Gore-Tex (polytetrafluoroethylene/PTFE)

- Originally used in vascular and abdominal surgery

- Inert, biocompatible, infection resistant, easily suturable and biointegrates by fibroblastic ingrowth (Wagner et al. 1984 and Karesh 1987)

- No need for second surgical site

- Reportedly low failure and complication rate (Steinkogler et al, 1992) (Kokubo et al, 2016)

Unilateral vs. bilateral surgery

- Unilateral surgery is generally preferred for simple unilateral poor levator function ptosis (Bernadini et al, 2007, 2013)

- The downside in congenital ptosis is that there is no drive to lift the ptotic brow, and amblyopia remains a risk.

- There can also be undesirable asymmetry because the brow frontalis lift on the ptotic side cannot match the levator lift on the other side.

- Bilateral surgery is sometimes advocated in unilateral congenital ptosis to improve symmetry

- Excision of the normal levator and bilateral frontalis suspension (Beard 1965)

- Can also be indicated for jaw winking ptosis (Cates and Tyers, 2008)

- Bilateral sling placement without excision of the normal contralateral levator (Callahan 1972)

- Equalizes palpebral fissure in primary gaze, downgaze (lid lag), and lagophthalmos with eyelid closure or blink

Open vs. closed technique

- Open

- Define eyelid crease

- Better symmetry (Bernardini et al. 2013)

- Slippage from tarsus

- Longer time in OR

- Closed

- Quick

- Good eyelid height and symmetry

- Lack of tarsal fixation

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Preoperative considerations

- Stop aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, and anticoagulants before surgery.

- Counsel patient on postoperative lagophthalmos and increased palpebral fissure on downgaze.

Postoperative instructions

- Lubricate the eye frequently due to postoperative lagophthalmos, lid lagophthalmos, and exposure concerns.

- Antibiotics to prevent postoperative wound infection, particularly with placement of nonautologous tissue

- Ice compresses to decrease swelling

Postoperative medications

- Cephalosporin

- Ocular lubricant: drops and ointment

- Antibiotic eye ointment

- Narcotic for postoperative pain

Management considerations

- Postoperative lagophthalmos guaranteed: Counsel patient beforehand.

- Increased palpebral fissure on downgaze (lid lag): Counsel patient beforehand.

- If ptosis is unilateral, result might be under-corrected. The drive to use brow is low.

- Other choices

- Bilateral frontalis suspension with preservation of normal levator

- Destroy good levator on contralateral/normal side and perform bilateral frontalis suspension

- Other choices

- Exposure keratopathy risks high when

- Patient is older

- Bells phenomenon is compromised

- Ocular motility is compromised (third nerve palsy)

- Frontalis suspension using autologous fascia lata in children under 3 years old

- Autologous fascia lata is an eligible material in frontalis suspension in children under 3 years old, despite the traditional oculoplastic dogma that advises against.

Complications

- Hemorrhage

- Infection

- Eyelash loss

- Overcorrection

- Undercorrection

- Lagophthalmos (predictable)

- Increased palpebral fissure on downgaze (lid lag; predictable)

- Corneal exposure keratopathy

- Corneal stippling

- Corneal abrasion

- Corneal ulceration

- Eyelid margin defect

- Entropion

- Ectropion

- Contour abnormality with eyelid notching

- Margin crease and margin fold asymmetries

References

- Aletaha M, Salour H, Bagheri A, Raffati N, Masoudi A. Modified frontalis sling procedure with lid crease formation. Journal of Ophthalmic and Vision Research 2013, 8: 134-138.

- Beard C. A new treatment for severe unilateral congenital ptosis and for ptosis with jaw winking. Americal Journal of Ophthalmology 1965, 59:252-8.

- Bertharia SM. Frontalis sling: amodified simple technique. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1985, 69: 443-445.

- Bernardini FP, Cetinkaya A, Zambelli A. Treatment of unilateral congenital ptosis: putting the debate to rest. Current Opinions in Ophthalmology 2013, 24: 484-87.

- Bernardini FP, Devoto MH, Prioolo E. Treatment of unilateral congenital ptosis. Ophthalmology 2007, 114: 622-3

- Bodian M. Repair of ptosis using human sclera. Am J Ophthalmol 1968; 65: 352-8.

- Broughton WL, Matthews JG, Harris DJ. Congenital ptosis: results of treatment using lysophilized fascia lata for frontalis suspension. Ophthalmology 1982, 89: 1261-6.

- Burnstine MA and Putterman AM.Upper blepharoplasty: a novel approach to progressive myopathic ptosis. Ophthalmology 1999, 2098-2100.

- Callahan A. Correction of unilateral blepharoptosis with bilateral eyelid suspension. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1972, 321-6.

- Carter SR, Meecham WJ, Seiff SR. Silicone frontalis slings for correction of blepharoptosis. Ophthalmology 1996, 103: 623-30.

- Cates CA and Tyers AG. Results of levator excision followed by fascia lata suspension in patients with congenital and jaw-winking ptosis. Orbit 2008; 27: 83-9.

- Crawford JS. Repair of ptosis using frontalis muscle and fascia lata. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1956, 60: 672-8.

- Davies BW, Bratton EM, Durauraj VD, Hink EM. Bilateral candida and atypical mycobacterial infection after rontalis sling suspension with silicone rod to correct congenital ptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013, 29: e111-e113.

- DeGroot V, DeWilde F, Smet L, Tassignon MJ. Frontalis suspension with blepharoplasty as an effective treatment for blepharospasm associate with apraxia of eyelid opening. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;16:34-8

- Fox SA. Complications of frontalis sling surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 1967, 63: 758-63.

- Friedhofer H, Nigro MVAS, Sturtz G, Ferreira MC. Correction of severe ptosis with a silicone implant suspensor: 22 years of experience. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2012, 453e-460e.

- Frueh, BR. The mechanistic classification of ptosis. Ophthalmology 1980, 87: 1019-21.

- Garcia-Cruz I, et al. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021 Jul-Aug;37(4):377-380.

- Helveston EM and Wilson DL. A Suture -Reinforced scleral sling. Technique for Suspension of the Ptotic Upper Eyelid. Arch Ophthalmol 1975, 93: 643-5.

- Karesh JW. Polytetrafluoroethylene as a graft material in ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery: an experimental and clinical study. OPRS 1987, 3: 179-85.

- Kokubo K, Katori N, Hayashi K, et al. Frontalis suspension with an explanded polytetrafluoroethylene sheet for congenital ptosis repair. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg 2016;69:673-78.

- Lane CM and Collin JR. Treatment of ptosis in chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1987, 71: 290-4.

- Lee MJ, Oh JY, Choung HK, Kim NJ, Sung MS, Khwarg SI. Frontalis sling operation using silicone rod compared with preserved fascia lata for congenital ptosis. Ophthalmology 2009; 119: 123-9.

- Liu D. Blepharoptosis correction with frontalis suspension using a supramid sling: duration of effect. Am J Ophthalmol 1999; 128: 772-3.

- Magnus JA. Correction of ptosis by two strips of fascia lata. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1936; 20: 460-4.

- Mehta P, Patel P, Olver JM. Functional results and complications of Mersilene mesh use for frontalis suspension ptosis surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 361-4.

- Morris CL, Buckley EG, Enyedi LB, Stinett S, Freedman SF. Safety and efficacy of Silicone Rod Frontalis Suspension Surgery for Childhood Ptosis Repair. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 2008, 45: 280-90.

- Raza Rizvi SA, Gupta Y, Yousuf S. Evaluation of safety and efficacy of silicone rod in tarsofrontalis sling surgery for severe congenital ptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2014, 30: 11-14.

- Salour H, Aletaha M, Bagheri A. Comparison of Mersiline mesha and autogenous fascia lata in correction of congenital blepharoptosis: A randomized clinical trial. European Journal of Ophthalmology 2009; 18: 853-7.

- Steinkogler FJ, Kuchar A, Huber E, Arocker-Mettinger E. Gore-Tex Soft-Tissue Patch Frontalis Suspension Technique in Congenital Ptosis and in Blepharophimosis-Ptosis Syndrome, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 1993; 92: 1057-1060.

- Tannenbaum RE, Shi W, Johnson TE, Wester, ST. Frontalis suspension with supramid suture: longevity results in very young patients with congenital ptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2014; 30: 110-115.

- Tillet CW and Tillet GM. Silicone sling in correction of ptosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1963; 62: 521-3.

- Wagner RS, Mauriello JA, Nelson LB, Calhoun JH. Flanagan JC, Harley RD. Treatment of congenital ptosis with frontalis suspension: a comparison of suspensory materials. Ophthalmology, 1984, 91:245-8.

- Wasserman BN, SPrunger DT, Helveston EM. Comparison of materials used in frontalis suspension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001, 119: 687-91.

- Wheatcroft SM, Vardy SJ, and Tyers AG. Complications of fascia lata harvesting for ptosis surgery. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1997; 81: 581-3.

- Wright WW. The use of living sutures in the treatment of ptosis. Archives of Ophthalmology 1922; 99-102.