Giant Cell Arteritis and Temporal Artery Biopsy

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Systemic granulomatous vasculitis involving medium to large arteries

- Most commonly the thoracic aorta, cervical arteries, and branches of the external carotid arteries

- Activated dendritic cells attract T-lymphocytes (mainly CD4) infiltration, macrophages exposed to IFN-γ form multinucleated giant cells

- Cytokine production including IFN-γ, IL-1b, IL-6, matrix metalloproteinases (MMP)

- Exact etiology unclear

- Some genetic predisposition, associated w/ HLA-DR4 haplotype

- Suggestion of infectious origin (mycoplasma, chlamydia, parvovirus B19, burkholderia)

- Age-related changes in the immune system and affected arteries might be important in disease pathogenesis.

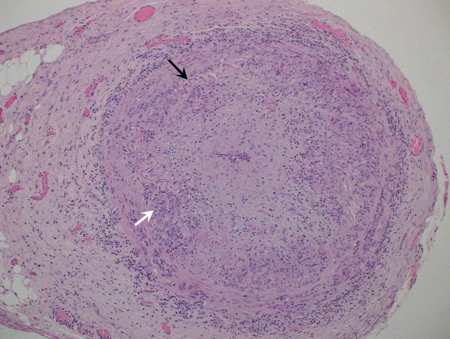

Figure 1. H&E photomicrograph of a medium sized artery with giant cell arteritis; note the multinucleated giant cells (arrow).

Epidemiology

- Incidence 18 per 100,000 in individuals over 50 years old (Salvarani, Ann Intern Med 1995)

- Elderly (mean age at presentation 71 years)

- Female > male (2–6 times greater); women account for 65%-75% of patients

- Most common in white people of northern European descent

- Unusual in Hispanic, Asian, and African-American populations

History

- Headache (present in 67%)

- Jaw claudication (present in 50%)

- Tongue claudication

- Scalp tenderness

- Systemic weakness, malaise, weight loss, fever

- Polymyalgia rheumatica (present in 40%–50%)

- Throat pain

- Nonspecific neck/shoulder/muscle pain

- Loss of vision

- Diplopia

- Eye pain

- In indeterminate specimens, CD68 staining for macrophages may be helpful

Clinical features

- Ophthalmic: Ischemic complications in 25% of giant cell arteritis (GCA) patients

- Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION): Accounts for about 80% of vision loss attributable to GCA

- Decreased vision: Often worse than 20/200, 21% NLP

- Can be preceded by transient vision loss

- Visual field defect: Typically central or altitudinal

- Afferent pupillary defect

- Swollen optic nerve head with pallor

- Optic atrophy usually evident after 3–6 weeks

- Posterior ischemic optic neuropathy (PION)

- Same as above, but optic nerve head initially appears normal

- Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) or cilioretinal artery occlusion

- Vision loss, afferent pupillary defect, cherry red spot

- Choroidal infarction

- Ischemic cranial nerve palsy

- Oculomotor nerve (nerve III) typically pupil-sparing

- Extraocular muscle infarction

- Ocular ischemic syndrome

- Hypotony due to decreased aqueous production

- Amaurosis fugax

- Horner syndrome

- Neurologic

- Ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), spinal cord infarction, mono/polyneuropathies, sensorineural hearing loss

- GCA can be “occult” (isolated ocular complications without other neurological findings) in 21%–38% of cases (Hayreh, Am J Ophthalmol 1997)

- Vascular

- Superficial temporal artery tenderness, lack of pulsation

- Thoracic/abdominal aortic aneurysm, coronary ischemia, intestinal infarction, pulmonary artery thrombosis, renal failure

- Upper or lower extremity claudication

Testing

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Nonspecific marker of inflammation

- Usually elevated (> 50 mm/hr in 85%–95% of patients)

- “Normal” ESR level subject of debate

- Miller formula (Miller, Br Med J 1983)

- Men: Age divided by 2

- Women: Age plus 10 divided by 2

- C-reactive protein (CRP)

- Usually elevated (> 2.45 mg/dL)

- When combined with elevated ESR, specificity is 97% (Hayreh, Am J Ophthalmol 1997)

- 4% of patients with confirmed GCA had normal ESR and normal CRP at time of diagnosis (Kermani, Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012)

- Thrombocytosis

- 65% of patients with permanent vision loss have thrombocytosis (Liozon, Am J Med 2001)

- Fluorescein angiogram

- AION: Delayed filling of optic disc or peripapillary choroid, choroidal nonperfusion

- CRAO: Delayed filling of CRA

- Duplex ultrasound of temporal artery

- Arterial edema represented by hypoechoic haloes immediately adjacent to arterial wall

- Sensitivity 75%, specificity 83% (Ball, Br J Surg 2010)

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 studies showed sensitivity of 68% (57%–78%; 95% CI) and specificity of 81% (75%–86%; 95% CI) (Rinagel, Autoimmune Rev 2019).

- Can be considered as noninvasive alternative to biopsy

- Temporal artery biopsy (TAB)

- Gold standard for definitive diagnosis of GCA

- Sensitivity 85–95% (Kermani, Ann Rheum Dis 2013)

- Positive predictive value 90%–100%

- Histopathologic findings

- T-lymphocyte and macrophage infiltrates of the vessel media and internal elastic lamina

- Giant cells might or might not be present

- Intimal thickening with disruption of internal elastic lamina

- Areas of unaffected tissue (skip lesions) in 21%–28% of cases

- Recommendations for biopsy length significantly

- Breuer (Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009) found increased biopsy length improved positivity rates: ≤ 5 mm (19%), 6–20 mm (79%), > 20 mm (89%)

- Recent systematic review of literature (Buttgereit, JAMA 2016) recommends specimen length of “at least 1 cm.”

- In a recent series of 240 temporal artery biopsies (Grossman, Scand J Rheumatol 2017), the TAB positivity rate was similar among all ranges of biopsy length (<5 mm 70%, 5-9 mm 71%, 10-14 mm 69%, 15-19 mm 69%, 20 mm 73% (p= ns).

- A case-control study of 545 consecutive patients who underwent TA biopsy (Oh, Anz J Surg 2018) found a cut-off point of > 15 mm increased the odds of a positive TAB by 2.25 compared with TAB < 15 mm (P= 0.003)

- Clinical judgment is warranted in the absence of a clear evidence-based minimum TA biopsy length

- Contralateral biopsy might be required if first biopsy negative (controversial).

- Positivity rate of second biopsy 9% (Hayreh, Am J Ophthalmol 1997)

- Bilateral biopsy can increase diagnostic sensitivity by up to 12.7% (Breuer, J Rheumatol 2009) but is generally not recommended as a primary approach.

- Systemic steroids can affect histopathologic findings, but should not be withheld prior to biopsy due to risks associated with treatment delay.

- Biopsy within 1–2 weeks of initiating steroid treatment might optimize diagnostic yield.

- Histopathologic evidence of GCA can still be seen after 6 months or more of steroid treatment (Narváez, Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007).

- Complications of procedure

- Bleeding, infection, pain, scarring, alopecia

- Scalp necrosis

- Damage to temporal branch of facial nerve (brow paralysis)

- Temporal artery biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis of GCA, but significant debate has emerged over whether temporal artery biopsy is necessary

- Clinicians should consider whether a positive or negative biopsy result will alter patient management

- If clinical suspicion is strong, treatment may be indicated regardless of TAB result.

- Temporal artery biopsy may not be required in patients with typical disease features and characteristic ultrasound or MRI findings (Dejaco, Ann Rheum Dis 2018)

- In paucity of signs and symptoms consistent with GCA, diagnostic yield of TAB is extremely low.

- Medico-legal ramifications: Positive TAB can justify risks of long-term steroid use

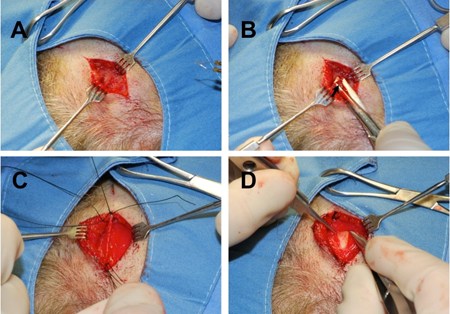

Figure 2. Temporal artery biopsy. (A) Scalp incision aided by preoperative doppler testing. (B) blunt dissection in subcutaneous fat and superficial temporal fascia to identify artery. (C) 2-cm arterial specimen to be obtained. (D) Deeper dissection demonstrates deep temporal fascia under the correct arterial plane.

American College of Rheumatology criteria

(Hunder, Arthritis Rheum 1990)

3 out of 5 of the following (sensitivity/specificity 93.5%/91.2%):

- Age at onset > 50 years

- New headache

- Temporal artery abnormalities (on exam or ultrasound)

- ESR > 50 mm/hr

- Positive temporal artery biopsy

Risk factors

- Increasing age

- Smoking and atherosclerosis: Increases risk in women but not men

- Low body mass index

- Early menopause

- Relative adrenal hypofunction

- Genetic susceptibility suggested by several studies

Differential diagnosis

- Nonarteritic ischemic optic neuropathy

- Other optic neuropathies (infectious, inflammatory, infiltrative, compressive, toxic)

- Nonarteritic central artery occlusion

- Central retinal vein occlusion

- Other causes of headache/jaw pain (trigeminal neuralgia, dental conditions)

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Disease course is chronic

- Visual prognosis depends on vision at presentation

- Incidence of blindness 7%–25%

- Vision loss due to AION or CRAO usually irreversible

- Features associated with poor visual prognosis: Older age, fever, weight loss, amaurosis, diplopia, jaw claudication

- 65% of untreated patients develop bilateral ischemic optic neuropathy.

- Vision loss in second eye typically occurs within 10 days of first.

- Failure to diagnose GCA is a significant cause of litigation against ophthalmologists.

Medical therapy

- Systemic corticosteroids: First line therapy

- Administration:

- Oral prednisone, typically 1 mg/kg/day

- IV administration for severe vision loss or amaurosis: Methylprednisolone 250 mg IV Q6 h for 3 days, then oral prednisone 80–100 mg/day

- Initiate steroids while awaiting biopsy results to avoid delay in treatment

- Follow ESR and clinical symptoms

- Symptoms typically respond within days

- Several weeks of steroids usually required before ESR/CRP normalize

- Visual improvement unusual, especially in AION and if delayed

- Decision to treat or stop treatment should be based on the complete clinical picture

- Taper corticosteroids slowly: A 1–2 year course typical

- Other medications

- Aspirin is often prescribed to prevent thrombotic complications.

- Efficacy in preventing blindness unproven

- Steroid-sparing agents:

- Adjunctive Methotrexate may reduce cumulative glucocorticoid dosing by 20%–44% and relapses by 36%–54% (Buttgereit, JAMA 2016)

- Methotrexate and IL-6 antagonist, Tociluzimab may each prevent the likelihood of relapse (Berti Semin Arthritis Rheum, 2018)

- In an RCT (Stone, NEJM 2017) Tociluzimab showed sustained remission at 52 weeks in 56% of weekly tociluzimab (with 26 week prednisone taper) vs 14% for the placebo (with 26 week prednisone taper)

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Steroid-related complications

- Inability to taper drug without flare of disease

- Hyperglycemia

- Aseptic necrosis of the hip

- Hypertension

- Osteoporosis

- GI bleeding

- Weight gain

- Cushingoid facies

- Depression

Prevention

- Limit long-term use

- Discuss side effects with patient before use

- Monitor for side effects (hyperglycemia, hypertension, osteoporosis, etc.) and treat as appropriate

Disease-related complications

- Ocular

- Permanent loss of vision

- Diplopia

- Neurologic

- Transient ischemic attack, stroke

- Vertigo

- Hearing loss

- Mononeuritis multiplex

- Coronary ischemia

- Aortic aneurysm or dissection

- Renal failure

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Tongue claudication/ischemia

Temporal artery biopsy technique

- Mark frontal branch of superficial temporal artery (STA) on symptomatic side, starting in preauricular region and extending toward forehead/brow:

- Locate artery by palpation or Doppler ultrasound.

- Incision should be at least as long as planned length of biopsy segment.

- Stay as distal to main STA trunk as possible.

- Shave scalp overlying STA if necessary.

- Infiltrate with local anesthetic, avoiding direct intravascular injection.

- Prep and drape surgical site in standard sterile fashion.

- Create skin incision parallel to artery, either directly overlying or slightly to either side.

- Bluntly dissect through subcutaneous fat to expose superficial temporalis fascia, also known as temporoparietal fascia.

- Superficial fascia is loose and areolar, as contrasted with underlying deep temporalis fascia, which is fibrous and glistening.

- Identify artery lying within superficial temporalis fascia.

- Spreading fascia with blunt-tipped instrument parallel to artery can assist in locating artery.

- Open fascia overlying the artery and dissect the artery from surrounding tissues:

- Avoid undue penetrating or crushing trauma to the specimen (e.g., with toothed forceps).

- Ligate and divide arterial branches as necessary.

- Double-ligate the artery both proximally and distally with braided nonabsorbable suture (for example, 4-0 or 5-0 silk), leaving adequate specimen length between ligation points.

- Ligating the artery early during procedure can limit intraoperative bleeding.

- Excise specimen and send in standard tissue fixative for pathologic examination.

- Obtain meticulous hemostasis.

- Close incision with deep and/or superficial skin sutures.

- Apply topical antibiotic ointment and dressing as desired.

- Instruct patient on proper wound care and precautions.

References and additional resources

- Ball EL, Walsh SR, Tang TY, et al. Role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. Br J Surg 2010;97:1765-71.

- Berti A, Cornec, D, Medina Inojosa J, et al. Treatments for giant cell arteritis: Meta-analysis and assessment of estimates using the fragility index. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018; 48:77-82.

- Breuer GS, Nesher G, Nesher R. Rate of discordant findings in bilateral temporal artery biopsy to diagnose giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol 2009;36:794-6.

- Breuer GS, Nesher R, Nesher G. Effect of biopsy length on the rate of positive temporal artery biopsies. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27:S10-3.

- Bury D, Joseph J, Dawson TP. Does preoperative steroid treatment affect the histology in giant cell (cranial) arteritis? J Clin Pathol 2012;65:1138-40

- Calvo-Romero JM. Giant cell arteritis. Postgrad Med J 2003;79:511-515.

- Dejaco C, Ramiro S, Duftner C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in large vessel vasculitis in clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77:636-643

- Duhaut P, Pinede L, Demolombe-Rague S, et al. Groupe de Recherche sur l’Artériteà Cellules Géantes. Giant cell arteritis and cardiovascular risk factors: a multicenter, prospective case-control study. J Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(11):1960.

- Fraser JA, Weyand CM, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The treatment of giant cell arteritis. Rev Neurol Dis 2008;5(3):140-152.

- Grossman C, Ben-Zvi I, Brashack I, BornsteinG. Association between specimen length and diagnostic yield of temporal artery biopsy, Scand J Rheumatol 2017; 46: 222-225.

- Hayreh S, Podhajsky PA, Raman R, Zimmerman B. Giant cell arteritis: validity and reliability of various diagnostic criteria. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;123;285-96.

- Hayreh S, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocular manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;125;509-20.

- Hayreh S, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Occult giant cell arteritis: ocular manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;125;521-6.

- Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1122-8.

- Kale N, Eggenberger E. Diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis: a review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:417-422.

- Gonzalez-Gay MA, Martinez-Dubois C, Agudo M, et al. Giant cell arteritis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2010;12:436-42.

- Karassa F, Matsaga MI, Schmidt WA, et al. Meta-analysis: test performance of ultrasonography for giant-cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:359-69.

- Kent RB, Thomas L. Temporal artery biopsy. Am Surgeon 1989;56:16-21.

- Koening CL, Katz BJ, Hernandez-Rodruiguez J, et al. Identification of a Burkholderia-like strain from temporal arteries of subjects with giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012:64:S373

- Liozon E,Hermann F, Ly K, et al. Risk factors for visual loss in giant cell (temporal) arteritis: a prospective study of 174 patients. Am J Med 2001;111:211-7.

- Miller A, Green M, Robinson D. Simple rule for calculating normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Br Med J 1983;286:266.

- Mizen TR. Giant cell arteritis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Ophthalmol Clin North Am 1991;4:547-56.

- Narváez J, Bernad B, Roig-Vilaseca D, et al. Influence of previous corticosteroid therapy on temporal artery biopsy yield in giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007;37:13-9.

- Oh LJ, Wong E, Gill AJ, et al. Value of temporal artery biopsy length in diagnosing giant cell arteritis. Anz J Surg 2018;88:191-195.

- Pineles SL, Arnold AC. Giant cell arteritis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2007;47:105-119.

- Quinn EM, Kearney DE, Kelly J, et al. Temporal artery biopsy is not required an all cases of suspected giant cell arteritis. Ann Vasc Surg 2012;26:649-54.

- Varma D, O’Neill D. Quantification of the role of temporal artery biopsy in diagnosing clinically suspected giant cell arteritis. Eye 2004;18:384-8.

- Vilaseca J, Gonzalez A, Cid MC, et al. Clinical usefulness of temporal artery biopsy. Ann Rheum Dis 1987;46:282-5.

- Rahman W, Rahman FZ. Giant cell (temporal) arteritis: an overview and update. Surv Ophthalmol 2005;50:415-28.

- Rinagel M, Chatelus E, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. Diagnostic performance of temporal artery ultrasound for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Autoimmune Rev 2019; 18:56-61.

- Salvarani C, Gabriel SE, O’Fallon WM, et al. The incidence of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: apparent fluctuations in a cyclic pattern. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:192-4.

- Stone JH, Tuckwell S, Dimonaco M, et al. Trial of Tociluzimab in giant cell arteritis. NEJM 2017; 377: 317-328.

- Swannell AJ. Polymyalgia rheumatic and temporal arteritis: diagnosis and management. Br Med J 1997;314:1329-32.

- Zhou L, Luneau K, Weyand CM, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in giant cell arteritis: a retrospective study of 107 cases. Ophthalmol, 2009; 116: 1574-1580.