Infantile Hemangioma

Updated July 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Definition

- Vascular tumor (Rootman, Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 2014)

- Arise after birth, during infancy

- Characterized by proliferating endothelial cells

- Usually undergoes spontaneous regression, either partial or complete

Pathogenesis

- Not known

- Angiogenesis (growth of vessels from preexisting vessels) and vasogenesis (growth of new vessels) may play a role

- Upregulation of endothelial cell markers in cultured cells (Jinnin, J Dermatol, 2010)

- Glucose transporter protein type-1 (GLUT-1)

- Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

- Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)

- Increased serum VEGF-A in patients with proliferating infantile hemangioma (Zhang, Plast Reconstr Surg, 2005)

- Infantile hemangioma stem cells express VEGF-A in proliferating phase

- VEGF production found to be blocked by dexamethasone (Greenberger, N Engl J Med, 2010)

- Cultured infantile hemangioma stem cells found to be capable of forming vessels without usual mesenchymal support (Khan, J Clin Invest, 2008)

Epidemiology

- Incidence of 4%–5% (Kilcine, Pediatr Dermatol, 2008)

- Usually occur sporadically (Callahan, Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2012)

History

- Usually present a few weeks to months after birth

- Undergo rapid growth phase followed by stable phase and then spontaneous gradual regression (Hernandez, Clin Ophthalmol, 2013)

Clinical features

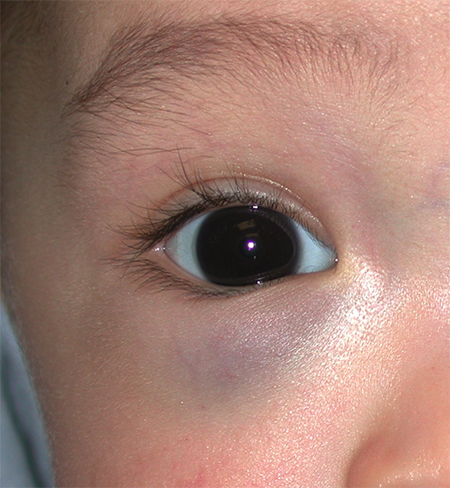

Figure 1. Large right upper eyelid infantile hemangioma obstructing the visual axis and causing occlusion amblyopia.

Figure 2. Infantile hemangioma of the orbit with only slight fullness and discoloration noted of the right lower eyelid.

Figure 3. Superficial infantile hemangioma of the left lower eyelid.

Figure 4. Extensive right upper eyelid infantile hemangioma. Although not occluding the visual axis, amblyopia can result from astigmatic anisometropia.

- Can occur anywhere on skin, usually in head and neck (Callahan, Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2012)

- Can be characterized by lesion depth (Callahan, Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2012)

- Superficial lesions

- Appear as bright red nodule

- Blanch with pressure (unlike port wine stains)

- Deep lesions

- Depending on depth, might have surface discoloration

- Combined superficial and deep lesions

- Can be characterized by area of involvement (Chiller, Arch Dermatol, 2002)

- Localized (focal)

- 72% of infantile hemangioma

- Segmental (involving multiple anatomical regions)

- 18% of infantile hemangioma

- Multifocal

- 3% of infantile hemangioma

- Can be part of PHACE syndrome (posterior fossa malformations, hemangioma, arterial abnormalities, cardiac defects/aortic coarctation, and eye abnormalities) (Coats, Ophthalmology, 1999)

- Etiology of PHACE unknown

- Possibly due to abnormal development of trigeminal nerve and cerebellum during first trimester

- More reported cases have occurred in females than in males.

- The most common arterial abnormality seen is coarctation of the aorta.

- Dandy-Walker malformation is the most common CNS malformation seen.

- Because of these associations, neuroimaging and cardiac evaluation is recommended for patients with large facial hemangiomas, especially if concurrent ophthalmic abnormalities are present

- Ophthalmic manifestations in 33% of patients with PHACE

- Reported ophthalmic abnormalities include

- Choroidal hemangiomas

- Cryptophthalmos

- Exophthalmos

- Colobomas

- Posterior embryotoxon

- Optic atrophy

- Microphthalmos

- Strabismus

- Optic nerve hypoplasia

- Glaucoma

Testing

- Diagnosis is often apparent based on clinical appearance (reddish discoloration, blanching with pressure).

- Complete eye exam including vision, refraction or retinoscopy (to determine presence of occlusive or astigmatic amblyopia), pupils and motility (for rare cases of orbital infantile hemangioma causing motility changes or compressive optic neuropathy)

- Imaging for unusual presentations or lesions with unclear depth of involvement

- Ultrasonography

- Increased vessel density with high flow (Callahan, Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2012)

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Moukaddam, Skeletal Radio, 2009)

- Well circumscribed lesion

- Hypointense to extraocular muscles on T1 sequence

- Hyperintense to extraocular muscles on T2 sequence

- Hyperintense with contrast administration

- Computed tomography (CT) (Rootman, Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 2014)

- Not recommended in children due to radiation exposure

- Well circumscribed

- Hyperintense with contrast administration

- Biopsy if diagnosis is unclear

- GLUT-1 endothelial cell marker is unique to infantile hemangioma and can help confirm the diagnosis (Leon-Villapalos, Br J Plast Surg, 2005)

Risk factors

Possible risk factors (Haggstrom, J Pediatr, 2007):

- Female gender

- Caucasian ethnicity

- Premature birth

- Low birth weight

- Multiple gestations

- Advanced maternal age

Differential diagnosis

(Callahan, Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2012)

Vascular tumors

- Congenital hemangiomas

- Fully formed at birth

- Rapidly involuting and noninvoluting types

- Kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas

- Aggressive growth

- Often present at birth

- Tufted angiomas

- Subcutaneous lesions with slow growth pattern

Vascular malformations

- Present from birth

- Formed from dysplastic vessels rather than proliferating endothelium

- Do not undergo spontaneous regression

- Port wine stain/nevus flammeus

- Can be associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome

- Firm rather than soft on palpation like infantile hemangioma

- Do not blanch with pressure

- Other orbital malformations include

- Lymphatic malformations

- Venolymphatic malformations

- Arteriovenous malformations

- However these lesions typically present later in life and do not have a similar appearance or clinical course to infantile hemangioma.

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

Clinical course has been described as having 6 stages (Chang, Pediatrics, 2008).

Nascent stage

- Immediately after birth

- Prior to emergence of visible lesion

- Usually 0–3 months

Early and late proliferative stages

- Rapid growth in early proliferative stage

- Less rapid growth in late proliferative stage

- Usually 6–10 months

- 80% of lesions reach maximum size by 5 months.

- Most lesions stop growing by 9 months.

- Deep and segmental lesions can have longer proliferative phase.

Stabilization phase

- Variable length

Involutional phase

(Margileth, JAMA, 1965)

- About 50% of lesions regress by age 4.

- About 75% regress by age 7.

Medical therapy

Observation

Good option for small lesions that are not causing

- Visual impairment

- Occlusive or astigmatic amblyopia

- Strabismus

- Proptosis

- Exposure keratopathy

- Compressive optic neuropathy

- Skin ulceration

- Disfigurement

Systemic beta blockers

(Propanolol)

- Currently the preferred intervention when large lesions require treatment

- Can work via vasoconstriction through nitrous oxide release, inhibition of VEFG and bFGF and apoptosis of proliferating endothelial cells (Storch, Br J Dermatol, 2010)

- Multiple case reports and case series have demonstrated good response.

- Case series of 17 patients: decrease in size in 100% (Haider, J AAPOS, 2010)

- Case series of 18 patients: similar findings (Missoi, Arch Ophthalmol, 2011)

- One Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial (Hogeling, Pediatrics, 2011)

- Was not specific to periocular lesions

- Stopped lesion progression in all patients by 4 weeks (versus 16 weeks for placebo group)

- Decrease in volume of lesion in propanolol group at all time points

- Side effects (Siegfried, N Engl J Med, 2008)

- Bradycardia

- Hypotension

- Bronchospasm

- Blunted hypoglycemic response

- Congestive heart failure

- Sleep disturbance

- Hypothermia

- Careful pretreatment history and monitoring during treatment are required.

- Patients/guardians should be informed of off-label use of medication.

Intralesional beta blockers

One prospective, nonrandomized study of 10 patients receiving intralesional triamcinolone 40 mg/ml and 12 patients receiving intralesional propanolol 1 mg/ml (Awadein, Clin Ophthalmol, 2011) reported a similar response.

- 40% “excellent” response

- 40%–45% “fair” response

- 17%–20% no response

Topical beta blockers

- Timolol 0.5%, which daily showed good response in 7 patients (Ni, Arch Ophthalmol, 2011)

- Reduction in size of 55%–95% in 4–8 weeks

- 73 patients with infantile hemangioma anywhere on skin treated with gel forming timolol maleate 0.1% or 0.5% twice daily (Chakkittakandiyil, Pediatr Dermatol, 2012)

- Good response with minimal side effects

- Potential treatment option for patients with superficial lesions

Systemic steroids

Systemic steroids at 2–5 mg/kg/day have been shown to be effective (Zak, J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus, 1981).

Prednisone at 20 mg daily for 3–8 weeks showed favorable response in 84% after 2 months (Bennett, Arch Dermatol, 2001).

- Some patients required up to 6 months.

- 35% rate of side effects

- Behavioral changes

- Cushingoid appearance

- Growth retardation

Intralesional steroids

(Kushner, Plast Reconstr Surg, 1985)

- Intralesional injection of 1–2 ml of 1:1 mixture of Betamethasone 6 mg/ml and triamcinolone 40 mg/ml

- Can see rapid improvement (within days)

- Infrequent but serious potential side effects

- Ophthalmic artery embolus

- Skin or fat atrophy or skin necrosis

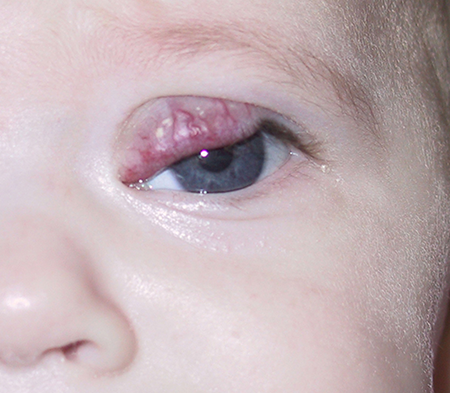

Figure 1. Four-month old infant with left upper eyelid hemangioma causing occlusion of the visual axis.

Figure 2. One month after intralesional corticosteroid injection has resulted in significant reduction in hemangioma size and now allows elevation of the upper eyelid.

Topical steroids

(Garzon, J Am Acad Dermatol, 2005)

- Clobetasol propionate, 0.05%, halobetasol propionate 0.05%, or betamethasone dipropionate used once or twice daily

- 33% with improvement, 33% with partial improvement, and 33% without improvement

- Potentially useful for superficial lesions

- Fewer side effects

- Hypopigmentation

- Hypertrichosis

- Glaucoma or cataract formation

Laser therapy

(Callahan, Saudi J Ophthalmol, 2012)

Argon laser, Nd-YAG laser, carbon dioxide laser, fractional photothermolysis and pulsed dye laser have been tried.

Pulsed dye laser is best studied and most widely used.

- Uses light of the same wavelength as the infantile hemangioma blood vessels

- Can be helpful for superficial lesions

- Penetration of 1.2 mm

- Required multiple passes, with 8 or more sessions every 1–2 months

- In one study of 617 patients, stopped growth in 97%, resolved lesions in 14%, and caused partial resolution in 15% (Hohenleutner, Lasers Surg Med, 2001)

- Side effects (Bennett, Arch Dermatol, 2001)

- Hyperpigmentation and atrophic scarring

- Primarily halt progression rather than cause regression of lesions

- Might have a role in select lesions, e.g., lesions causing skin ulceration

Surgery

- Usually reserved for patients who have not responded to nonsurgical treatment

- Side effects

- Bleeding risk

- Can use various techniques including preemptive ligation and cauterization of vessels prior to excision to minimize blood loss

Figure 3. Fifteen-month old child with residual hemangioma of the left upper eyelid resulting in a persistent chin-up head positioning despite treatment with oral propranolol and intralesional corticosteroid injections.

Figure 4. Two weeks after surgical debulking and excision of the left upper eyelid hemangioma.

Disease-related complications

Ambylopia is the most common ophthalmic complication.

- 40%–60% of infantile hemangioma patients (Haik, Ophthalmology, 1979)

- Occlusive amblyopia

- Anisometropic amblyopia due to induced astigmatism

- Periocular lesions greater than 1cm may increase risk of amblyopia (Schwartz, J APPOS, 2006)

- Orbital lesions are less common but may cause serious complications (Haik, Ophthalmology, 1979)

- Strabismus

- Proptosis

- Exposure keratopathy

- Compressive optic neuropathy

- Disfigurement or potential for future disfigurement (Boscolo, Angiogenesis, 2009)

- 40%–80% of lesions can have residual scarring even after tumor resolution

- Skin ulceration (Holland, Pediatr Clin North Am, 2010)

- More common in nonperiocular regions

- Infantile hemangioma in the neck can cause airway obstruction (Holland, Pediatr Clin North Am, 2010).

- Multifocal infantile hemangioma can have systemic implications (Holland, Pediatr Clin North Am, 2010).

- High output heart failure due to multiple hemangiomas

- As part of PHACE syndrome

Historical perspective

- First described by Lister; referred to as strawberry nevi (Lister, Lancet, 1938)

- Systemic steroids found to be efficacious by chance during treatment of a child with thrombocytopenia (Katz, In XI International congress of pediatrics, Tokyo, 1965)

- Systemic beta blocker (propanolol) found to be efficacious by chance during treatment of a patient with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (Léauté-Labrèze, N Engl J Med, 2008)

References and additional resources

- Lueder GT. Infantile hemangioma: are intralesional steroids dead? American Academy of Ophthalmology Oculofacial Plastic Surgery Subspecialty Day Meeting 2013. https://www.aao.org/annual-meeting-video/infantile-hemangioma-are-intralesional-steroids-de

- National Organization of Vascular Anomalies. http://www.novanews.org

- The Vascular Birthmarks Foundation. http://birthmark.org

- http://infantilehemangioma.com

- Awadein A., Fakhry M.A. Evaluation of intralesional propranolol for periocular capillary hemangioma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1135–1140.

- Bennett M.L., Fleischer A.B., Jr, Chamlin S.L., Frieden I.J. Oral corticosteroid use is effective for cutaneous hemangiomas: an evidence-based evaluation. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(9):1208–1213.

- Boscolo E., Bischoff J. Vasculogenesis in infantile hemangioma. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:197–207.

- Callahan AB, Yoon MK. Infantile hemangiomas: a review. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:283-291.

- Chakkittakandiyil A., Phillips R., Frieden I.J. Timolol maleate 0.5% or 0.1% gel-forming solution for infantile hemangiomas: a retrospective, multicenter cohort study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:28–31.

- Chang L.C., Haggstrom A.N., Drolet B.A., Baselga E., Chamlin S.L. Hemangioma investigator group. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics.2008;122(2):360–367.

- Chiller K.G., Passaro D., Frieden I.J. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567–1576.

- Coats DK, Paysse EA, Levy ML. PHACE: a neurocutaneous syndrome with important ophthalmologic implications: case report and literature review. Ophthalmology;106(9):1739-1741.

- Garzon M.C., Lucky A.W., Hawrot A., Frieden I.J. Ultrapotent topical corticosteroid treatment of hemangiomas of infancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(2):281–286.

- Greenberger S., Boscolo E., Adini I., Mulliken J.B., Bischoff J. Corticosteroid suppression of VEGF-A in infantile hemangioma-derived stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(11):1005–1013.

- Haggstrom A.N., Drolet B.A., Baselga E., Chamlin S.L., Garzon M.C. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: demographic, prenatal, and perinatal characteristics. J Pediatr. 2007;150(3):291–294.Hemangioma investigator group.

- Haider K.M., Plager D.A., Neely D.E., Eikenberry J., Haggstrom A. Outpatient treatment of periocular infantile hemangiomas with oral propranolol. J AAPOS. 2010;14(3):251–256.

- Haik B.G., Jakobiec F.A., Ellsworth R.M., Jones I.S. Capillary hemangioma of the lids and orbit: an analysis of the clinical features and therapeutic results in 101 cases. Ophthalmology. 1979;86(5):760–792.

- Hernandez J, Chia A, Quah, BL, Seah LL. Periocular capillary Hemangioma: management practices in recent years. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1227-1232.

- Hogeling M., Adams S., Wargon O. A randomized controlled trial of propranolol for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2011;128(2):e259–e266.

- Hohenleutner S., Badur-Ganter E., Landthaler M., Hohenleutner U. Long-term results in the treatment of childhood hemangioma with the flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser: an evaluation of 617 cases. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28(3):273–277.

- Holland K.E., Drolet B.A. Infantile hemangioma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57(5):1069–1083.

- Jinnin, M., Ishihara T., Boye E., Olsen B.R. Recent progress in studies of infantile Hemangioma. J Dermatol, 2010;37(11):939-955.

- Katz HP. Thrombocytopenia associated with hemangiomata: critical analysis of steroid therapy. In XI International congress of pediatrics, Tokyo; 1965, p. 336–7.

- Khan Z.A., Boscolo E., Picard A., Psutka S., Melero-Martin J.M., Bartch T.C. Multipotential stem cells recapitulate human infantile hemangioma in immunodeficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2592–2599.

- Kilcline C., Frieden I.J. Infantile hemangiomas: how common are they? A systematic review of the medical literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(2):168–173.

- Kushner B.J. The treatment of periorbital infantile hemangioma with intralesional corticosteroid. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76(4):517–526.

- Léauté-Labrèze C., Dumas de la Roque E., Hubiche T., Boralevi F., Thambo J.B., Taïeb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2649–2651.

- Leon-Villapalos J., Wolfe K., Kangesu L. GLUT-1: an extra diagnostic tool to differentiate between haemangiomas and vascular malformations. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58:348–352.

- Lister W.A. The natural history of strawberry naevi. Lancet. 1938;1:1429–1434.

- Margileth A.M., Museles M. Cutaneous hemangiomas in children. Diagnosis and conservative management. JAMA. 1965;194(5):523–526.

- Missoi T.G., Lueder G.T., Gilbertson K., Bayliss S.J. Oral propranolol for treatment of periocular infantile hemangiomas. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(7):899–903.

- Moukaddam H., Pollak J., Haims A.H. MRI characteristics and classification of peripheral vascular malformations and tumors. Skeletal Radio. 2009;38:535–547.

- Ni N., Langer P., Wagner R., Guo S. Topical timolol for periocular hemangioma: report of further study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(3):377–379.

- Rootman J, Heran MKS, Graeb D. Vascular malformations of the orbit: classification and the role of imaging in diagnosis and treatment strategies. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;30(2):91-104.

- Schwartz S.R., Blei F., Ceisler E. Risk factors for amblyopia in children with capillary hemangiomas of the eyelid and orbit. J AAPOS. 2006;10:262–268.

- Siegfried E.C., Keenan W.J., Al-Jureidini S. More on propranolol for hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2846.

- Storch C.H., Hoeger P.H. Propranolol for infantile haemangiomas: insights into the molecular mechanisms of action. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(2):269–274.

- Zak T.A., Morin J.D. Early local steroid therapy of infantile eyelid hemangiomas (local steroid therapy of lid hemangiomas) J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1981;18(1):25–27.

- Zhang L., Lin X., Wang W., Zhuang X., Dong J., Qi Z. Circulating level of vascular endothelial growth factor in differentiating hemangioma from vascular malformation patients. Plast Reconstr Surg.2005;116:200–204.