Keratoacanthoma of the Eyelid

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Keratoacanthomas are low-grade squamous cell carcinoma variant that uniquely involute in some cases.

Etiology

Most research on the etiology of this lesion has been performed on non-eyelid keratoacanthomas.

- In a study of 98 non-eyelid keratoacanthomas, using array comparative genomic hybridization, genetic instability was observed in both the growth and involutional phases of this self-limiting cutaneous neoplasm (Li 2012).

- Genomic instabilities differed between KA and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) suggesting that they are distinct entities despite their histopathologic similarities.

- Deletion of the tumor suppressor gene p53 was observed in 27% of KAs, and 46% of SCC.

- Genetic aberrancy is most noticeable in chromosomes 7, 8, and10.

- In a study of 92 non-eyelid keratoacanthomas, more than 60 different types of HPV DNA were identified, suggesting that no specific HPV type plays an etiologic role in KA (Ekstrom 2011).

- Although previously considered a benign eyelid growth, keratoacanthomas are now felt to be more of a premalignant form of squamous cell carcinoma (in situ), and cells at the base of the lesion have been observed to progress to frank squamous cell carcinoma, in 5% of 3465 non-eyelid cases in one study, even higher in elderly patients (Weedon 2010).

Epidemiology

- In a study of 44 eyelid keratoacanthomas identified in the files of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, from military, civilian and Veterans Administration sources, the average age was 49 years (range 19–96 years) (Boniuk 1967).

- 27 were men and 17 were women (male predominance likely reflecting the military sources at that time).

- 13 were upper lid, 25 lower lid, and the rest canthal.

- 13 lesions occurred at the lid margin.

- Keratoacanthoma is generally more common in middle age and older patients

- There is some association with sun exposure, with some series documenting a higher incidence in Hawaii and Australia

- Although usually solitary, there are syndromes associated with multiple lesions:

- Muir-Torre syndrome: autosomal dominant, sebaceous tumors of the skin, associated with colon cancer

- Variant of Grzybowski syndrome: sporadic, large numbers of smaller keratoacanthoma-like lesions

- Ferguson Smith syndrome: autosomal dominant, keratoacanthomas appear in adolescence, spontaneously involute, then recur at older age

History

- Rapid growth (weeks to months) is the classic description.

- History of prior lesions

- Other types of cutaneous lesions

- Family history is also important

Clinical features

- Begins as a small flesh colored to slightly reddish mass

- Most often a solitary lesion with smooth, rolled, elevated edges surrounding a central core of keratin

- Often exhibits rapid growth, when it develops its more classic appearance

- Skin colored, often with signs of mild erythema

Testing

- Biopsy is the only way to establish the diagnosis.

- A biopsy involving the rolled lesion edges is necessary to confirm malignancy.

- The classic histopathologic description is a dome-shaped lesion with central keratin-filled crater.

- Beneath the crater there is acanthotic epithelium maturation as cells progress from deeper to more superficial.

- The base of the lesion is irregular and not a well-circumscribed mass, as seen in an inverted follicular keratosis.

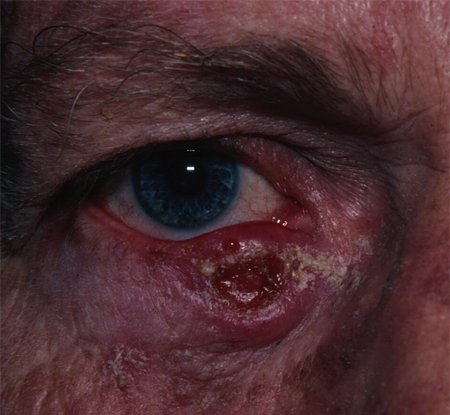

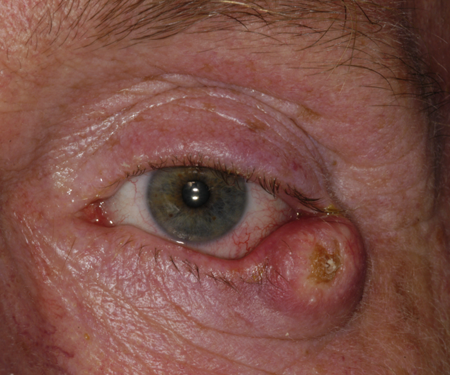

Figure 1. Keratoacanthoma. Courtesy Rona Z. Silkiss, MD, FACS.

Figure 2. Keratoacanthoma. Courtesy Evan H. Black, MD.

Figure 3. Keratoacanthoma. Courtesy Raymond Cho, MD.

Figure 4. Keratoacanthoma. Courtesy Michael J. Hawes, MD, FACS.

Figure 5. Same Keratoacanthoma, 6 weeks later. Courtesy Michael J. Hawes, MD, FACS.

Risk factors

- UV (artificial or natural), X-ray

- Immunosuppression (pathologic, iatrogenic)

- Trauma to skin and/or foreign bodies (including iatrogenic, cosmetic i.e. tattoos, filler, laser)

- Tar

- BRAF & Hedgehog pathway inhibition

- Familial (Kwiek B, Schwartz RA.)

Differential diagnosis

- Basal cell carcinoma

- High-grade squamous cell carcinoma

- Eyelid abscess

- Insect or spider bite

- Trauma

- Giant molluscum confluence

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Natural history is rapid growth, stabilization, and occasional spontaneous regression.

- Overall prognosis is good with complete surgical excision or spontaneous involution.

Medical therapy

- Medical therapy is limited for eyelid lesions, although topical and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents have been used in lesions elsewhere.

- Cryotherapy and radiation therapy have been reported.

Surgery

- As involution cannot be predicted, surgical resection with clear margins is recommended as with other squamous cell carcinomas. This is often performed in conjunction with Mohs micrographic surgery to ensure clear margins.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

- Surgical excision with adequate margin should be curative.

- Recurrence can be managed with repeat excision.

- Systemic retinoid has been reported to allow for complete resolution of eyelid KA in a patient on vemurafinib (Sachse MM, Fenchel K, Wagner G.)

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Cryotherapy

- Lash loss

- Eyelid irregularities

- Eyelid retraction or cicatricial ectropion

- Recurrence

- Skin necrosis

- Surgical excision

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Scarring

- Corneal abrasion

- Globe perforation

- Eyelid retraction or cicatricial ectropion

- Recurrence

- Complications are prevented with:

- Infections are treated with topical and oral antibiotics.

- Scarring can be treated with topical or intralesional corticosteroids, and surgery when indicated.

- Cicatricial ectropion and retraction might require skin graft.

Disease-related complications

- Mechanical ectropion

- Visual obstruction

- Induced astigmatism

- Conversion to invasive squamous cell carcinoma

Historical perspective

- Keratoacanthoma was established as a clinical entity in 1936 by MacCormac and Scarff.

- Its occurrence in the periorbital region was first described by Christensen and Fitzpatrick as a case report in 1955.

References and additional resources

- Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids and Lacrimal System, 2010–2011. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology.

- Boniuk M, Zimmerman LE. Eyelid tumors with reference to lesions confused with squamous cell carcinoma. 3. Keratoacanthoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;77(1):29-40.

- Christensen L, Fitzpatrick TB. Keratoacanthoma of the eyelid. Arch Ophthalmol. 1955;53(6):857-859.

- Ekstrom J, Bzhalava D, Svenback D, et al. High throughput sequencing reveals diversity of Human Papillomavirus in cutaneous lesions. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(11):2643-2650.

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): An update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Jun;74(6):1220-33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.033. Epub 2016 Feb 4. PMID: 26853179.

- Li J, Wang K, Gao F, et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization of keratoacanthomas and squamous cell carcinomas: different patterns of genetic aberrations suggest to distinct entities. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(8):2060-2066.

- Sachse MM, Fenchel K, Wagner G. Regression of B-RAF inhibitor associated keratoacanthomas by acitretin – how do retinoids act on the RAF/MEK/ERK-signaling pathway? J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014 Aug;12(8):721-3. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12323. Epub 2014 Jul 1. PMID: 24981739.

- Weedon DD, Malo J, Brooks D, Williamson R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in keratoacanthoma: a neglected phenomenon in the elderly. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32(5):423-426.