Le Fort Fractures

Updated August 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

The Le Fort classification system describes 3 common fracture lines associated with maxillary trauma and craniofacial dysjunction. These patterns were observed initially in cadaveric experiments after slow-velocity blunt trauma. In modern practice, they are rare in isolation, but elements of these fractures are commonly seen after high-velocity, blunt facial trauma.

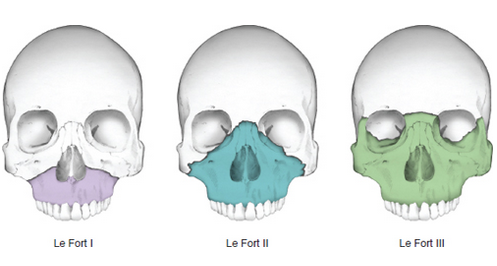

Figure 1. Le Fort’s classification of midfacial fractures. Le Fort I, horizontal fracture of the maxilla, also known as Guerin fracture. Le Fort II, pyramidal fracture of the maxilla. Le Fort III, craniofacial dysjunction. Modified by Cyndie C. H. Wooley from Converse JM, ed. Reconstructive Plastic Surgery: Principles and Procedures in Correction, Reconstruction, and Transplantation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1977:2.

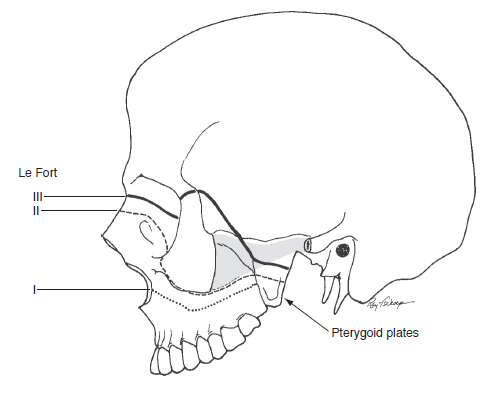

Figure 2. Le Fort fractures, lateral view. Note that all the fractures extend posteriorly through the pterygoid plates (arrow). Modified from Converse JM, ed. Reconstructive Plastic Surgery: Principles and Procedures in Correction, Reconstruction, and Transplantation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1977:2.

Epidemiology

There have been varying trends, but motor-vehicle collisions and interpersonal violence are the 2 most common causes of maxillofacial fractures. Falls and sports injuries are less common causes.

It has been reported that about 25% of patients being treated in a hospital setting after a motor-vehicle collision will have sustained midfacial fractures. A large percentage of these will include elements of a Le Fort I, II, or III fracture.

Ocular injury has been reported in 24%–28% of facial fracture cases. Cervical spine injury is also found in 1.3% of patients with facial fractures and 4% of patients with facial injury from motor-vehicle collision.

History

The specific history of the trauma including the mechanism of injury, timing, and other interventions already undertaken should be elicited. Specific trauma circumstances can give insight into the type of injuries to be expected — e.g., panfacial fractures in unrestrained passenger in a high-speed motor-vehicle collision, zygomaticomaxillary complex (ZMC) fractures after assault with a metal object to the face, orbital fractures after assault with a closed fist — or necessitate further interventions, e.g., social services consultation after domestic abuse, investigation for “second jaw” lacerations in animal bites, searching for foreign bodies after windshield trauma.

In conscious patients, history should focus on the patient’s breathing, vision, diplopia, occlusion, prior facial trauma, and ocular disease, and on review of prior photographs of the patient.

In addition to the facial fractures and ocular injury, a multidisciplinary team needs to be coordinated to manage the airway, cervical spine, and any intracranial concerns.

Clinical features

- The classic Le Fort midfacial fractures are common injury patterns involving a fracture to the maxilla that extends through the pterygoid plates. The 3 classic patterns are

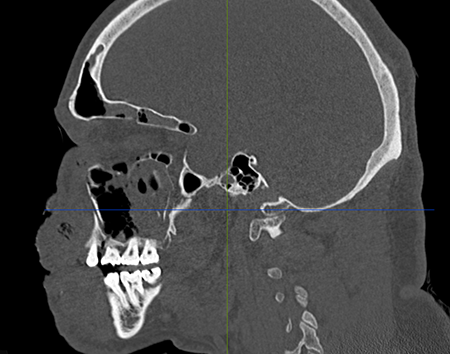

- Le Fort I, AKA Geurin fracture: low transverse fracture through maxilla alveolus with no orbital involvement (Figure 4) creating a floating segment containing the palate and upper teeth and is often at the piriform aperture

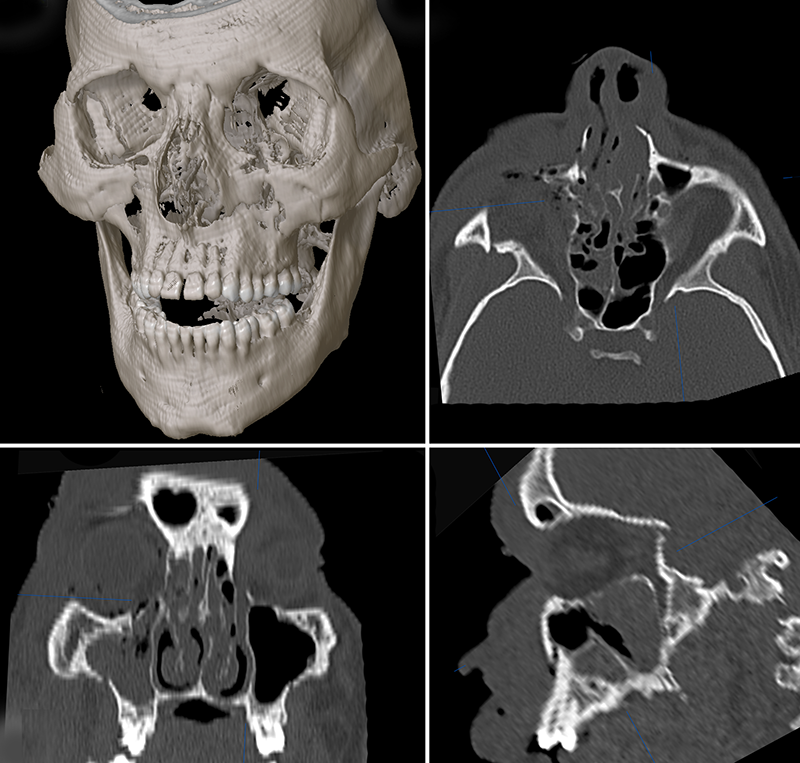

- Le Fort II, AKA pyramidal fracture: fracture through the nasal bridge, lacrimal, and maxillary bones extending through the medial orbital floor and inferior orbital rim near the infraorbital foramen and then inferiorly along the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus (Figure 4), creating a floating segment including the lacrimal crests, the maxilla, the upper teeth, and the palate

- Le Fort III, AKA craniofacial dysjunction: Craniofacial dysjunction in which the fracture is through the nasal bridge, entire orbit, and laterally through the fronto-zygomatic suture completely detaching the lower facial skeleton from the skull base and suspended only by soft tissues (Figure 5)

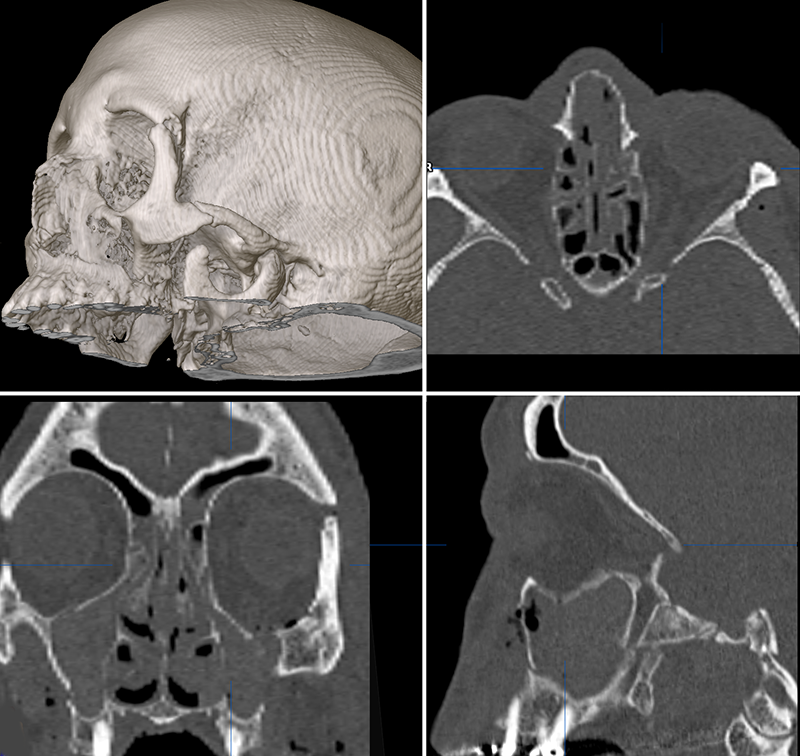

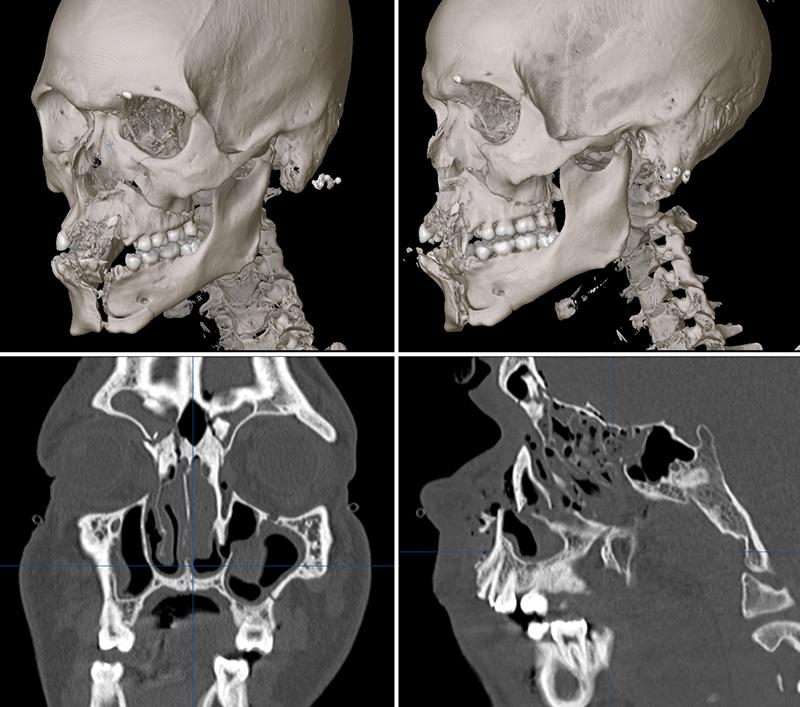

- It is important to recognize that, even experimentally, multiple Le Fort fracture lines often occur and that clinically they are unlikely to be found “cleanly” (i.e., noncomminuted), symmetrically, or in isolation (Figures 3–5).

- As this system represents an escalating level of dysjunction of the midface from the cranial vault, Le Fort fractures should be described on each side corresponding to the most superior fracture line (Figure 6).

- A useful way to think about the orbital component of Le Fort II and III fractures is to consider the other complex fractures of the orbit: the naso-orbital ethmoidal (NOE) and ZMC fractures. That is, both the Le Fort II and III involve an NOE fracture and a fracture through the pterygoid plates. A Le Fort II fracture also involves a fracture through the orbital rim and floor, as seen at the medial extent of most ZMC fractures, whereas a Le Fort III involves a fracture of the zygomatic-frontal and zygomatic-sphenoid junctions, as seen at the lateral and posterior extent of most ZMC fractures.

Figure 3. Le Fort I fracture in sagittal plane.

Figure 4. Le Fort II fracture.

Figure 5. Le Fort III fracture.

Figure 6. Le Fort I and II fracture.

Testing

- Clinical ophthalmic and orbital exam:

- Visual acuity for signs of ocular injury such as traumatic optic neuropathy, hyphema, ruptured globe, retinal edema, or retinal tear

- Extraocular motility exam and the presence of pain or diplopia with movement

- Pupil exam for signs of an afferent pupillary defect, sphincter tear, ruptured globe, or traumatic mydriasis

- Facial sensation/infraorbital nerve evaluation

- Globe position with exophthalmometry and vertical position assessment

- Canthal assessment to evaluate for telecanthus

- Soft-tissue examination for lacerations and eyelid malposition

- Palpation of orbital rim for step deformities

- Additional facial exam:

- Airway compromise assessment

- Facial nerve function

- Soft tissue assessment for Battle’s sign (bruising over mastoid)

- Midfacial retrusion assessment

- Intraoral exam to assess bite for dental occlusion abnormality (often anterior open bite) and intraoral bruising

- Intranasal exam for bleeding or cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea

- Midface segment mobility exam: Stabilize forehead with one hand, grasp anterior alveolar arch/upper teeth with the other, and pull forward; can be immobile with severe impaction.

- Radiographic exam:

- Although plain films such as PA and Water’s views can demonstrate sinus bleeding and fracture lines, modern assessment requires imaging with CT scan.

- Thin-slice noncontrast facial CT scan or spiral scan to allow for multiplanar reformatting to view images in the coronal, axial, and sagittal planes

Risk factors

Seat belt use has been reported to decrease the risk of maxillofacial injury by 72%.

Differential diagnosis

Other facial fractures:

- Zygomatic maxillary complex fractures

- NOE fractures

- Internal orbital fractures (floor and/or medial wall fractures)

- Optic canal fractures

- Pertinent patient management in terms of treatment and follow-up

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

If not repaired, extensive fractures of the midface are often associated with significant functional and cosmetic deformities.

Medical therapy

Although fractures ultimately might need to be reduced and repaired surgically, immediate medical therapy can include antibiotics, nasal decongestants, and restriction of nose-blowing in patients with traumatic orbitosinus connection. Oral or IV steroids can reduce swelling, but have not shown a benefit to long-term outcomes for either optic neuropathy or facial fractures.

Surgery

Urgent interventions might be needed for

- Maxillary displacement with airway compromise: Maxillary disimpaction can be performed manually or with the use of large disimpaction forceps.

- Orbital injuries threatening the integrity of extraocular muscles or the optic nerve; see orbital fractures.

When neurologically and clinically stable, surgical repair involves

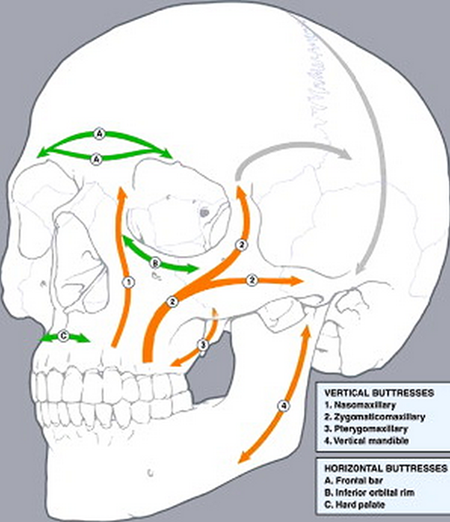

- Open reduction and fixation of unstable segments to more stable cranial and lower facial skeleton components. Often the stable elements constitute one or more of the unfractured facial buttresses (Figure 7). Plate and screw fixation using one or more of the following incisions is often performed:

- A bicoronal incision to the nasofrontal region and zygomatic arch

- A lower-eyelid incision (e.g., retroseptal transconjunctival, preseptal transconjunctival, subciliary transcutaneous) to the internal orbit and rims

- A buccal sulcus incision to the maxilla

- Restoration of proper dental occlusion with maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) in the relaxed mandibular position (such as with elastics, arch bars).

- Disimpaction if required; be wary of a nonmobile maxilla because there are reports of aggressive attempted disimpaction in an incompletely fractured maxilla that resulted in the creation of an unpredictable fracture. The direction of dislocation with disimpaction forceps can drive the posterior maxillary wall upward and through the optic canal.

- Reduction and fixation of other segments using mini-plate and micro-plate systems

- Repair of orbital fractures

- Splinting of the palate if split

Figure 7. System of buttresses. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier from European Journal of Radiology. Imaging of high-energy midfacial trauma: what the surgeon needs to know. KF Linnau, RB Stanley, DK Hallam, et al. 2003; 48(1):17-32.

Other management considerations

Postoperative care should be reviewed with instructions given to

- Maintain oral hygiene with meticulous brushing of teeth and arch bars

- Limit diet to pureed and liquid foods

- Remove the MMF in case of vomiting

- Follow up with eye provider with any changes in vision, diplopia

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

Late repair requires extensive mobilization of fracture elements, often with osteotomies. As exposure needs to be greater to create a safe osteotomy relative to that needed for surgical repair, early repair is preferable.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Postoperative orbital hemorrhage: Surgically drain if vision compromised (canthotomy, cantholysis, and placement of drain).

- Postoperative vision loss:

- Rule out optic nerve injury from displaced bone fragments.

- Repeat CT scan.

- Consider corticosteroids.

- Rule out orbital hemorrhage.

- Malocclusion deformity if reduction is poor or fixation loosens: Avoid with meticulous reduction and fixation.

- Maxillary lengthening: Minimize with maxillomandibular fixation (MMF)

- Injury to dental roots from misplaced screws:

- Avoid placing screws in area of tooth roots

- Consider MMF

- Infraorbital or supraorbital nerve injury with persistent hypesthesia: Take care to identify and preserve these nerve roots.

- Injury to frontal branch of facial nerve from excess traction on coronal flaps

- Infection

- Lower eyelid ectropion or retraction are more common after lower eyelid approaches.

Disease-related complications

The following can occur with or without surgical treatment:

- Facial nerve injury

- Sensory nerve injury with persistent hypesthesia

- Injury to teeth

- Soft tissue injury complications

- Chronic sinusitis or mucocele

- Facial deformities

- Nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- Ophthalmic injury

Historical perspective

In 1901, French surgeon Rene Le Fort published his observations regarding fractures of the upper jaw. His work elucidated the commonalities for maxillary fractures, but it was originally his intent to help predict what fractures would occur based on the history of an injury in the difficult practice of a battlefield surgeon. Using fresh intact cadavers, he created slow-velocity blunt trauma at various angles and with a variety of weights of wooden clubs. It was often reported that he dropped decapitated heads from windows although it is more likely that he dropped them onto a tabletop.

Le Fort’s nomenclature has lasted more than 100 years in clinical use, but the increasing prevalence of high-velocity trauma from motor-vehicle collisions and increasing firearm power has since required an updated understanding of the injuries that occur in the maxillofacial skeleton.

Many contributions were made by Paul Manson and Joseph Gruss regarding high velocity facial trauma patterns and management of panfacial fractures. Although the old Le Fort I, II, and III nomenclature is still in use, their work from the 1980s and early 1990s as CT scanning was becoming standard and plate-and-screw fixation was being refined led to many observations regarding Le Fort II fractures as well as Le Fort IV fractures involving the frontal sinuses, orbital roof, and anterior skull base.

References and additional resources

- Chien-Tzung C, Chen R-F, Wei F-C. Craniofacial Trauma and Reconstruction. In: Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. New York: Springer; 2010:290-294.

- Le Fort R. Étude expérimentale sur les fractures de la machoire supérieure. Revue chir de Paris. 1901; 23: 208-227, 360-79, 479-507.

- Gruss JS, Bubak PJ, Egbert MA. Craniofacial fractures. An algorithm to optimize results. Clin Plast Surg. 1992;19(1):195-206.

- Fraioli RE, Branstetter BF 4th, Deleyiannis FW. Facial fractures: beyond Le Fort. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(1):51-76.

- Manson PN. The Management of Midfacial and Frontal Bone Fractures. In: Plastic, Maxillofacial and Reconstructive Surgery. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997:351-76.

- Manson PN. Some thoughts on the classification and treatment of Le Fort fractures. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;17(5):356-363.

- Mendes M, Borba M, Sawazaki R, Asprino L, de Moraes M, Moreira RW. Maxillofacial trauma and seat belt: a 10-year retrospective study. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;17(1):21-25.

- Perkins CS, Layton SA. The aetiology of maxillofacial injuries and the seat belt law. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;26(5):353-363

- Richards AM. Le Fort Fractures. In: Key Notes on Plastic Surgery. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2002:132-3.