Ocular Adnexal MALT Lymphoma

Updated July 2024

Antonio G. Resti, MD; Andrés J. M. Ferreri, MD; Maurilio Ponzoni, MD; Letterio S. Politi, MD

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Biological and molecular data suggest that ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (OAML) is an antigen-driven lymphoproliferative disorder.

Autoimmunity and/or chronic infection might drive lymphoid proliferation.

- Association with Sjögren’s syndrome and thyrotoxicosis (5% of cases) favor autoimmunity (Ferreri, Ann Oncol 2008).

- 30-40% of ocular adnexal MALT patients are seropositive for hepatitis C virus and up to 80% harbor Chlamydia infection, favoring chronic infection (Ferreri, Ann Oncol 2008).

- Chlamydophila psittaci has been shown in the cytoplasm of tumor cells and macrophages (Ponzoni, Clin Cancer Res 2008).

- In vitro culture has demonstrated that the chlamydia organisms are vital and infectious in both the blood and conjunctiva of conjunctival MALT patients (Ferreri, IJC 2009).

- These patients more commonly live in rural areas, and often report a history of chronic conjunctivitis and prolonged household or professional exposure to animals (Dolcetti, BJC 2012).

- Gastric infection by H. pylori has been detected in one third of patients with ocular adnexal MALT but correlation patient and disease characteristics and lymphoma regression after bacteria eradication have not been demonstrated (Ferreri, HemOnc 2006).

- Chlamydophila psittaci is the etiologic agent of avian chlamydiosis in birds and psittacosis-ornithosis in humans, a zoonotic disease caused by the exposure to infected animals, mostly birds (Ferreri, Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2009).

- All Chlamydophila psittaci genotypes recognized so far can be transmitted to humans, but it is a rare infection in European individuals (IgG-seropositive rate of only 3% in elderly individuals).

- The use of topical or systemic antibiotics before biopsy may mask the association in some patients, yielding false negative results.

Epidemiology

- More than 75% of adnexal lymphomas are unilateral.

- More common than follicular lymphoma, diffuse large cell-lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma

- Females are more commonly affected, with a median age of 60 years.

- No races differences have been reported.

- A 6% increase in annual incidence of this lymphoma has been reported (Maanon, JNCI 2005).

History

- Conjunctival irritation, swelling, redness often misdiagnosed and treated for conjunctivitis

- More commonly painless, often completely asymptomatic, incidental finding

- Orbital lymphoma can present with slow progression of proptosis or palpable mass.

- Often misdiagnosed as thyroid orbitopathy

- Can present as ptosis or other mass effect such as diplopia

- Lacrimal gland lymphoma can present as enlarged gland or unilateral dry eye

- Can be discovered incidentally after CT or MRI performed for other reasons

Clinical features

- Conjunctival lymphoma appears as subconjunctival mass

- Gelatinous appearance, salmon pink color

- Painless

- Insidious progressive onset, which often leads to delay in diagnosis

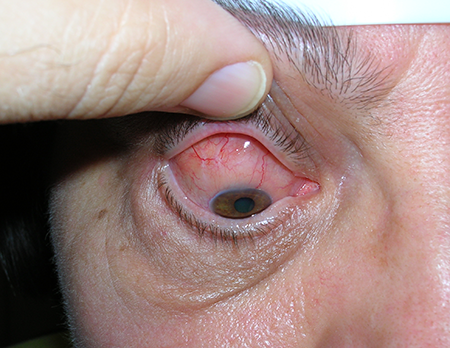

- Conjunctival lymphoma can localize to the lower fornix (Figure 1) or upper fornix (Figure 2) or diffusely infiltrate (Figure 3)

- Orbital lymphoma can cause proptosis, mass, ptosis, dry eye, motility deficit, or rarely, visual decline (Figure 4)

Figure 1. MALT lymphoma of the lower fornix.

Figure 2. MALT lymphoma of the upper fornix.

Figure 3. Diffuse conjunctival MALT lymphoma.

Figure 4. Pseudoptosis by large lymphoma of the upper temporal quadrant.

Testing

- Diagnosis is made on histopathological examination.

- Requires open biopsy with removal of at least 1 cm3 of tissue if possible

- Needle aspiration cytology is mostly inadequate for establishing a diagnosis

- For conjunctival tumor the diagnosis might be strongly suspected on clinical inspection of gelatinous pink salmon tissue, but biopsy is still recommended

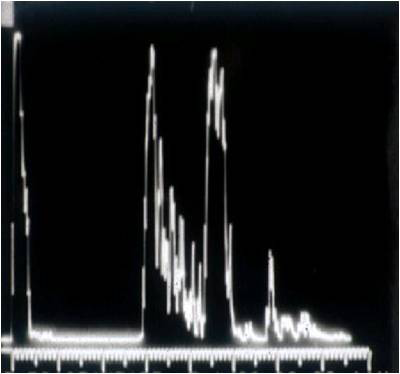

- Ultrasonography: A-scan demonstrates mass with low internal reflectivity (Figure 5)

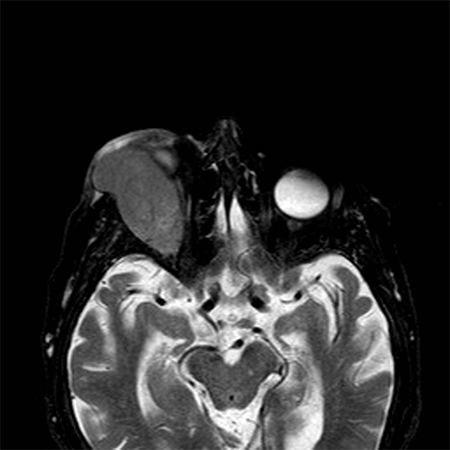

- MRI typically demonstrates well-defined mass with lobulated margins or ill-defined infiltrating tumor also possible

- Typically homogeneous and isointense compared with the cerebral cortex on T2- weighted images (Figure 6)

- T1-weighted image without contrast typically iso- to hyperintense compared with cerebral cortex

- Gadolinium contrast MRI typically shows homogeneous contrast enhancement with signal intensity similar to normal lacrimal glands and extraocular muscles (Figure 7)

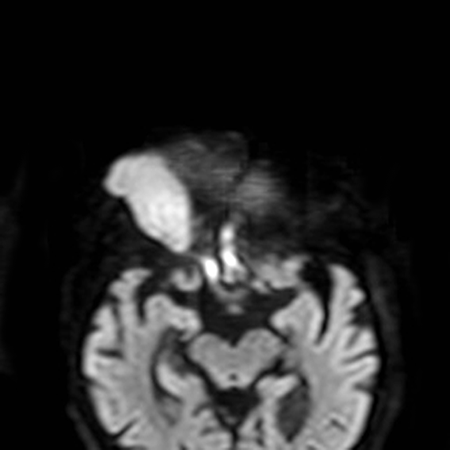

- Diffusion-weighted MRI typically hyperintense compared with other orbital structures (Figure 8)

- Hypointense on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) map suggests restriction of water diffusivity (Figure 9) (Politi, Neurology 2010)

- In a study of 96 orbital mass-lesions, an ADC threshold of 775 x 106 mm2/sec resulted in 96% sensitivity, 93% specificity, 88% positive predictive value, 98.2% negative predictive value compared with other neoplastic and non-neoplastic orbital lesions

- An ADC threshold of less than 920 x 106 mm2/sec distinguished lymphoma from inflammation with 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity

- Characteristic immunophenotype is CD20+, CD3-, CD5-, CD23-, CD10-, cyclin D1-, with a proliferation rate usually less than 20%

Figure 5. Ultrasound standardized A-scan of an orbital lymphoma.

Figure 6. On the T2-weighted image, the lesion appears as a huge mass arising from the lachrymal gland and isointense to the cerebral cortex.

Figure 7. On the post-contrast T1-weighted image, the ocular adnexal lymphoma presents homogeneous contrast enhancement.

Figure 8. On the DWI image the lesion is bright, suggesting restricted water diffusivity.

Figure 9. The dark appearance of the lymphoma on the ADC map confirms the reduction of the diffusivity, which thus indicates high cellularity.

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

More than 75% of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma presents with a single lesion (stage IE).

Regional lymphadenopathy is detected in < 5% of cases (stage IIE).

Extraocular extranodal disease is observed in 10%–15% of cases (stage IVE).

Extraocular disease is rare with conjunctival lymphoma.

With more extensive testing at least one concomitant, extraorbital site of disease is found in up to 38% of patients but the usefulness of extended staging is a matter of debate.

An extensive gastrointestinal work-up in the absence of clinical symptoms suggestive of lymphoma does not seem necessary.

Risk factors

- Possession of domestic animals, especially birds

- Occupational exposure to potentially infected animals by Chlamydophila psittaci (Dolcetti, BJC 2012)

- Seropositivity for hepatitis C virus is present in a statistically significant amount of patients with OAML and is associated to a more aggressiveness of the disease (Ferreri, Ann Oncol 2006)

Differential diagnosis

- Chronic conjunctivitis

- Dry eye syndrome

- Benign lymphoproliferative disorders (Differential diagnosis based on MR and histological findings)

- Inflammatory pseudotumor (Differential diagnosis based on MR and histological findings)

- Other tumors of the lacrimal gland (clinical history, rapid development, pain, CT and RM findings, histology)

- Other tumors of the orbit (clinical history, rapid development, pain, CT and RM findings, histology)

- Thyroid orbitopathy clinical history of thyroid disease, bilateral exophthalmos, eyelid retraction, inflammation, CT and MR appearance

- Tumors of the lacrimal sac

- Eyelid ptosis

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Prognosis is generally good, with malignancy usually confined to primary site.

- Systemic dissemination occurs in 5%–10% of cases, especially rare in patients with conjunctival lymphoma.

- Some anecdotal cases of spontaneous tumor remission have been reported.

- Assumes that patients have not been treated with topical steroids or antibiotics

- Some patients experience multiple relapses, involving contralateral orbit and distant extranodal organs.

- Reliable prognostic factors remain to be defined.

- “Wait and watch” strategy after resection or biopsy in patients with stage I-disease produces results similar to treatment with radiotherapy, with 10-year survival of 94%.

Medical therapy

Universally accepted guidelines for the medical management of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma do not exist.

The eradication of chlamydial infection with doxycycline (100 mg orally twice a day for 3 weeks) has been proposed as a valid therapeutic strategy (Ferreri, JCO 2009; Ferreri, JCO 2012).

Half of patients experience objective lymphoma regression, which is more evident and long-lasting when the bacterial eradication is verified (Ferreri, JCO 2012).

Clinical trials have confirmed that doxycycline is a fast, safe, cost-effective therapy for chlamydia-positive patients.

Reinfection due to prolonged contact with infected pets or the effect of other concomitant infections (i.e., hepatitis C virus) could result in reduced efficacy of this biological treatment.

Antiviral combination therapy with peginterferon and ribavirine has produced encouraging results in HCV-positive patients with OAML.

Macrolide antibiotics in particular have a direct antiproliferative effect, and 2 small prospective trials have shown that half of patients achieve lymphoma regression with a prolonged exposure to oral clarithromycin.

Experience with chemotherapy is still limited.

Combination therapy with alkylating agents such as bendamustine and chlorambucil and the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab is associated with a 90%–100% overall response rate and a 5-year relapse-free survival of 90%.

The efficacy of monotherapy in MALT lymphoma patients is significantly lower.

Radiation

Radiotherapy is the most extensively studied treatment in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma, but a universally accepted radiation schedule does not exist.

Recent studies suggest a radiation field including a gross tumor volume with 0.5- to 1-cm margin for a planning target volume and a dose of 25–30 Gy in 10 to 15 fractions (minimal target dose > 25 Gy).

Electron beams (4-12 MeV) and 4-9 megavolt photon beams are advisable in conjunctival and orbital lymphomas, respectively.

Ultra-low dose radiation 4 Gy to the orbit(s) in two 2-Gy fractions has been described (Pinnix,JAMA Oncology, 2024).

- Persistent orbital lymphoma can undergo additional 20 Gy in 10 fractions In the prospective cohort, 22 patients were treated for newly diagnosed stage I MALT lymphoma, the 2-year freedom from distance recurrence rate for these patients was 95.2% (95% CI, 86.6%-100%) at 2 years.

A single anterior field or a wedge pair of anterior fields have been used in most series.

In conjunctival lymphoma, the entire conjunctiva and eyelid should be irradiated.

Preliminary data seem to suggest that the entire orbit should be irradiated in patients with intra-orbital lymphoma.

Response is usually slow and gradual.

In-field relapses are rare and seem to be related to low radiation doses or to the use of shielding lens.

Relapse rate at 4 years is 20-25%; half of relapses involve the contralateral orbit.

90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®), an anti-CD20 radioimmunoconjugate has been used in a few cases of limited disease and is an alternative.

Surgery

Surgical biopsy is a necessary diagnostic step.

Some tumors might be amenable to primary resection.

Surgery is an option for aesthetic reasons in cases.

Other management considerations

Intralesional injection of biological agents like interferon and rituximab might have efficacy.

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

Less than 5% of ocular adnexal lymphoma patients die of lymphoma, with a 5-year cause-specific and overall survival of 100% and > 90%, respectively.

Local control rates vary according to therapy, with a 5-year relapse-free survival of roughly 65%.

Relapses of limited-stage OAML are usually in the primary sites of disease.

Examination and gadolinium-enhanced MRI of the orbits should be performed every six months for the first five years of follow-up and once a year afterward.

Specific investigation of distant organs is indicated only with clinical suspicion.

Treatment of relapsing disease depends on patient’s age and comorbidity, previous antilymphoma therapies, extension and site of relapse, as well as duration of response to the previous treatment.

Local therapies for orbital or conjunctival relapses include surgical resection and intralesional therapies, whereas orbital reirradiation is associated with high risk of complications.

Systemic therapies include chemotherapy, immunotherapy and antibiotics; importantly, these therapies can be repeated in the case of previous long-lasting responses.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Most treatments for ocular adnexal lymphoma are well tolerated.

Side effects of intralesional therapies include local hemorrhage, chemosis, and minor systemic effects.

Chemotherapeutic agents tested in small prospective trials, such as everolimus, lenalidomide and bortezomib, have been associated with relevant toxicity, hematological, and neurological in particular.

Myelotoxicity of varied severity are well-known complications of alkylating agents, requiring sometimes rHuG-CSF support and antimicrobial prophylaxis.

The most common toxicities of grade ≥ 2 of radiotherapy are cataract (38% of cases), retinal disorders (17%), xerophthalmia (17%), and glaucoma (2%).

Toxicity is more common with doses > 36 Gy.

Disease-related complications

- Visual acuity reduction and visual field defects

- Diplopia

- Pain

- Keratopathy due to dry eye or exophthalmos

- Systemic complication from diffuse tumor dissemination is rare.

Historical perspective

In early 1990s, Peter Isaacson is credited with demonstrating the association between gastric lymphoma and chronic gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori (Lancet 1991; 338:1175).

In 2004, a similar relationship was suggested between ocular adnexal lymphomas and chronic infection by Chlamydophila psittaci (J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96:586).

In 2008, the presence of Chlamydia in the tissue of ocular adnexal lymphoma was demonstrated by Ponzoni M, et al. by using four different methods (Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:5794).

In 2008, Ferreri et al. demonstrated that Chlamydophila psittaci is viable and infectious in the conjunctiva and peripheral blood of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma patients (Int J Cancer 2008; 123:1089).

In 2012, Ferreri et al. reported a phase II trial on doxycycline as first-line therapy for ocular adnexal lymphomas (J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:2988).

References and additional resources

- Dagklis A, Ponzoni M, Govi S, et al: Immunoglobulin gene repertoire in ocular adnexal lymphomas: hints on the nature of the antigenic stimulation. Leukemia. 2012 Apr;26(4):814-21.

- de Cremoux P, Subtil A, Ferreri AJ, et al: Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98:365.

- Decaudin D, Dolcetti R, de Cremoux P, et al: Variable association between Chlamydophila psittaci infection and ocular adnexal lymphomas: methodological biases or true geographical variations? Anticancer Drugs 2008;19:761.

- Dolcetti R, Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Doglioni C. Genetic and epigenetic changes linked to Chlamydophila psittaci-associated ocular adnexal lymphomas. Hematol Oncol 2010; 28:1.

- Dolcetti R, Serraino D, Dognini G, et al: Exposure to animals and increased risk of marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of the ocular adnexae. Br J Cancer 2012; 106:966.

- Ferreri AJ, Assanelli A, Crocchiolo R, et al: Therapeutic management of ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2007; 8:1073.

- Ferreri AJ, Dognini GP, Ponzoni M, et al: Chlamydia-psittaci-eradicating antibiotic therapy in patients with advanced-stage ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2008;19:194.

- Ferreri AJ, Dolcetti R, Dognini GP, et al: Chlamydophila psittaci is viable and infectious in the conjunctiva and peripheral blood of patients with ocular adnexal lymphoma: results of a single-center prospective case-control study. Int J Cancer 2008; 123:1089.

- Ferreri AJ, Dolcetti R, Du MQ, et al: Ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: an intriguing model for antigen-driven lymphomagenesis and microbial-targeted therapy. Ann Oncol 2008; 19:835.

- Ferreri AJ, Dolcetti R, Magnino S, Doglioni C, Ponzoni M. Chlamydial infection: the link with ocular adnexal lymphomas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2009 ; 6:658.

- Ferreri AJ, Ernberg I, Copie-Bergman C. Infectious agents and lymphoma development: molecular and clinical aspects. J Intern Med 2009; 265:421.

- Ferreri AJ, Govi S, Pasini E, et al: Chlamydophila psittaci eradication with doxycycline as first-line targeted therapy for ocular adnexae lymphoma: final results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:2988.

- Ferreri AJ, Govi S, Ponzoni M. Marginal zone lymphomas and infectious agents. Semin Cancer Biol 2013; 23:431.

- Ferreri AJ, Guidoboni M, Ponzoni M, et al: Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96:586.

- Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Dognini GP, et al: Bacteria-eradicating therapy for ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: questions for an open international prospective trial. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1721.

- Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, et al: Bacteria-eradicating therapy with doxycycline in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: a multicenter prospective trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98:1375.

- Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, et al: Regression of ocular adnexal lymphoma after Chlamydia psittaci-eradicating antibiotic therapy. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:5067.

- Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Martinelli G, et al: Rituximab in patients with mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Haematologica 2005; 90:1578.

- Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Viale E, et al: Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and MALT-type lymphoma of the ocular adnexa: clinical and therapeutic implications. Hematol Oncol. 2006 Mar;24(1):33-7.

- Li ZM, Spagnuolo L, Mensah AA, et al: Gains of CCND3 gene in ocular adnexal MALT lymphomas: an integrated analysis. Br J Haematol 2013; 160:719.

- Pinnix CC, Dabaja BS, Gunther JR, Fang PQ, Wu SY, Nastoupil LJ, Strati P, Nair R, Ahmed S, Steiner R, Westin J, Neelapu S, Rodriguez MA, Lee HJ, Wang M, Flowers C, Feng L, Esmaeli B. Response-Adapted Ultralow-Dose Radiation Therapy for Orbital Indolent B-Cell Lymphoma: A Phase 2 Nonrandomized Controlled Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2024 Jul 11:e242112.

- Politi LS, Forghani R, Godi C, et al: Ocular adnexal lymphoma: diffusion-weighted mr imaging for differential diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring. Radiology 2010; 256:565.

- Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Doglioni C, Dolcetti R. Unconventional therapies in ocular adnexal lymphomas. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2010; 10:1341.

- Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Guidoboni M, et al: Chlamydia infection and lymphomas: association beyond ocular adnexal lymphomas highlighted by multiple detection methods. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:5794.

- Ponzoni M, Govi S, Licata G, et al: A reappraisal of the diagnostic and therapeutic management of uncommon histologies of primary ocular adnexal lymphoma. Oncologist 2013;18:876.

- Sepahdari AR, Politi LS, Aakalu VK, et al: Diffusion-weighted imaging of orbital masses: multi-institutional data support a 2-ADC threshold model to categorize lesions as benign, malignant, or indeterminate. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35:170.

- Vargas RL, Fallone E, Felgar RE, et al: Is there an association between ocular adnexal lymphoma and infection with Chlamydia psittaci? The University of Rochester experience. Leuk Res 2006; 30:547.

- Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG: Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet 1991; 338:1175.