Marcus Gunn Jaw-Winking Syndrome

Updated July 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

Synkinetic ptosis: aberrant connection between branches of the trigeminal nerve (V3) innervating the external pterygoid muscle and fibers of the superior division of the oculomotor nerve (III) innervating the levator palpebrae superioris muscle.

Rare cases can involve the internal pterygoid muscle fibers or other muscle groups (Davis, Eye 2004).

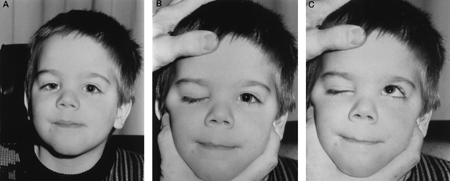

Wink reflex or momentary upper-eyelid elevation to an equal or higher level than fellow eye occurs on stimulation of ipsilateral pterygoid muscle (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Characteristic change in eyelid height with jaw movement in Marcus Gunn jaw wink phenomenon. Courtesy Raymond Cho, MD

Epidemiology

- Usually sporadic with no inheritance pattern

- Most often evident at birth

- Accounts for 2%–13% of congenital ptosis cases (Demirci, Ophthalmol 2010)

- 0.22 age- and gender-adjusted incidence per 100,000

- Marcus jaw wink can occur in the absence of ptosis in 6% of cases (Pearce, OPRS 2017)

- Can be associated with strabismus or double-elevator palsy

- Can occur with slightly increased frequency on left side

- Bilateral or alternating jaw-wink are rare (Sobel, OPRS 2014)

History

- Presence and degree of ptosis

- Synkinetic upper-eyelid movement occures with:

- Wink first noticed while baby is breastfeeding or bottle feeding

- Mouth opening, jaw movement or protrusion

- Teeth clenching, chewing, sucking or swallowing

- Change in vision

- Diplopia

- Past ocular history

- Occlusion therapy for amblyopia

- Strabismus surgery

- Eyelid surgery

- Dry eyes: important if contemplating ptosis surgery

- Periorbital or head trauma suggests aberrant III nerve regeneration if accompanied by bizarre extraocular movements and diplopia

- Past medical history

- Details of birth history

- Previous reactions to anesthesia

Clinical features

- Variable degrees of blepharoptosis

- Variable degrees of synkinetic upper-eyelid retraction on jaw movement; worse in down gaze

- Superior rectus or double elevator palsy can be present, as for any case of congenital ptosis

- Strabismus

- Hypotropia (43%), exotropia (3%), esotropia (1%) (Mukherjee 2023)

- Chin up position

- Consider amblyopia if chin elevation is absent despite moderate to severe ptosis

Testing

- Visual acuity: rule out amblyopia in infants and children

- Cycloplegic refraction: rule out anisometropia

- Extraocular motility and cover test: rule out superior rectus or double elevator palsy

- Ptosis evaluation

- Degree of ptosis should be evaluated with jaw immobilized in central position and after fusion disrupted with brief ocular occlusion of ipsilateral side (Wong, OPRS 2001)

- Figure 2 illustrates the difference in eyelid measurements without versus with the jaw fixated

- Failure to perform this maneuver can lead to under correction and/or choice of improper surgical technique

- Eyelid measurements to quantify

- Ptosis: mild (≤ 2 mm lower than normal), moderate (3 mm), or severe (≥ 4 mm)

- Levator function: good (≥ 8 mm), fair (5–7 mm), or poor (≤ 4 mm)

- Lid excursion due to jaw winking: mild (≤2 mm), moderate (3-6 mm) and severe (≥7 mm)

- Eyelid position in down gaze

- Measurement of contralateral eyelid position

- Jaw wink is usually considered cosmetically significant if ≥ 2 mm

- Synkinetic eyelid movement

- Elicit wink

- Have the infant bottle-feed or suck on pacifier

- Open mouth, move jaw from side to side, or protrude jaw forward

- Attempt to quantify jaw wink

Figure 2. Difference in eyelid height measurement without and with the jaw properly fixated.

Risk factors

- Congenital ptosis

- One case reported in association with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and the PHOX2B mutation (Basu, Neurology 2012)

Differential diagnosis

- Aberrant III nerve regeneration

- Double-elevator palsy

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

Marcus Gunn jaw-winking syndrome is associated with strabismus in approximately 50%–60% of cases; usually superior rectus or double elevator palsy.

The incidence of anisometropia is reported to be 5%–25% (refractive difference between two eyes of ≥ 1.25 diopters of sphere or 1 diopter of cylinder).

Amblyopia occurs in 30%–50%; almost always secondary to strabismus or anisometropia, and only rarely due to occlusion by a ptotic eyelid.

Although it has been suggested that jaw winking improves over time, it is more likely that patients stop seeking care as they get older or learn to compensate for and mask the wink response.

Medical therapy

Treat any amblyopia aggressively with occlusion therapy and/or correction of anisometropia prior to any consideration of ptosis surgery.

Depending on the type of deviation, management of strabismus may need to occur before ptosis surgery.

- Vertical muscle imbalance should be managed before ptosis to avoid ptosis under correction (Bowyer, OPRS 2004)

Surgery

Consider eyelid surgery only when parents or patient and the surgeon agree about whether the most cosmetically objectionable condition is the ptosis or wink, or a combination of both. Mild cases may be monitored.

If the jaw wink is small or cosmetically insignificant, it can be ignored in the treatment of the ptosis.

- Mild ptosis with good levator function:

- Müller muscle and conjunctival resection, Fasanella-Servat procedure, or standard external levator resection

- Moderate to severe ptosis with moderate to good levator function:

- External levator resection

- Severe ptosis with moderate to good levator function:

- Super maximum (> 30 mm) levator resection

- Frontalis suspension

- Severe ptosis with poor levator function:

- Frontalis suspension silicone sling or fascia lata

- Frontalis suspension with muscle flap

If the jaw wink is significant, any attempt to repair the ptosis without addressing a significant jaw wink will result in an unacceptable exaggeration of the aberrant eyelid movement to a level above the superior corneal limbus.

- In these cases, a partial ptosis correction can be performed limiting the exaggeration of the wink

- Some authors report unilateral frontalis suspension without levator disinsertion or extirpation that can reduce the severity of jaw wink (87% cases) (Shah OPRS 2020)

- In most cases, elimination of levator function and resuspension of the eyelid to the brow is necessary

- There are many techniques described for the correction of jaw-winking ptosis, reflecting an ongoing controversy regarding the surgical management of this condition:

- Surgical techniques for ablating levator function

- Levator excision via anterior approach

- Standard trans-eyelid anterior dissection

- Incise levator aponeurosis from anterior tarsal plate and dissect superiorly to just below Whitnall’s ligament:

- Blunt dissect from Mueller’s muscle

- Release the medial and lateral horns

- Clamp just above Whitnall’s ligament with a hemostat or ptosis clamp (approximately 20 mm above tarsal end of aponeurosis) and use bipolar cautery along the entire length prior to excision

- Alternatively, a 1 cm section of levator can be excised ABOVE Whitnall’s ligament:

- Use muscle hooks to isolate the levator above Whitnall’s

- Use hemostat and bipolar cautery to define and excise a 1 cm segment above Whitnall’s ligament

- Levator excision via posterior approach (Bowyer, OPRS 2004)

- 4-0 silk traction sutures through anterior lid margin

- Evert over Desmarres retractor

- Incise conjunctiva and Mueller’s muscle above the superior tarsal border

- Blunt dissect Mueller’s from the underside of the levator muscle

- Incise levator aponeurosis posterior to anterior:

- Confirm in the preaponeurotic space by identifying preaponeurotic fat

- Proceed with excision of levator muscle as above

- Levator fixation to the superior arcus marginalis

- Proceed as above with the anterior approach except do not excise muscle superiorly

- Anchor distal edge of levator to the superior arcus marginalis

- Allows for reattachment if needed in the future (theoretically)

- Unilateral versus bilateral surgery

- Some advocate bilateral levator ablation and frontalis suspension for optimal symmetry (Beard, AJO 1965)

- Parents are rarely accepting of this approach

- Some advocate for bilateral frontalis suspension alone in moderate to severe cases (Khwang, Ophthalmology 1999)

- Others propose ablating levator on affected side only and then bilateral frontalis suspension (Callahan, AJO 1973)

- Parents are rarely agreeable to this approach either

- Others advocate unilateral levator excision and frontalis suspension on affected side only (Kersten, OPRS 2005)

- Parents are more accepting of this approach

- Other Surgical Techniques

- Orbicularis oculi flap to correct the jaw wink in small case series (Tsai, Ann Plastic Surg 2002)

Other management considerations

- Superior rectus palsy

- Superior rectus muscle resection: only in absence of inferior rectus muscle restriction

- Because superior rectus muscle is loosely bound to overlying levator, the upper eyelid will be pulled inferiorly during resection, exacerbating any ptosis already present

- Double-elevator palsy

- Deficit in elevation in all fields of gaze: result of superior rectus and inferior oblique palsy and/or inferior rectus restriction

- A combined superior rectus and inferior oblique palsy usually requires a Knapp procedure

- Sequential strabismus surgery

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

- Lower success rate than equivalent ptosis without jaw wink

- 10% recurrence rate (or higher) in some series (Demirci, Ophthalmol 2012)

- Standard post-op protocols and follow-up as indicated for cases of congenital ptosis

- Management of persistent jaw wink after surgery

- Many authors recommend waiting one year before readdressing

- Basic management involves progression to next “degree” of jaw-wink surgery

- For example, if levator was not initially excised, proceed to excision

- If levator was excised, the patient may need more aggressive re-excision or release of scar adhesions

- Management of under-corrected ptosis

- Defer re-operation for at least 3 months

- Except if there is a risk of occlusive amblyopia

- Under-corrected levator resection (if jaw wink not severe)

- Repeat levator resection

- Removal of scar tissue

- Proceed to frontalis suspension (any approach)

- Under-corrected frontalis suspension with adequate frontalis use

- Revision of primary procedure

- Revision with different suspension material or different approach; Frontalis or levator suspension

- Under-corrected frontalis suspension with poor frontalis use

- Proceed with contralateral frontalis suspension

Preventing and managing treatment complications

Under-correction or asymmetry of ptosis repair

- Revise as necessary as described above.

Overcorrection of ptosis with exposure keratopathy

(without frontalis suspension)

- Conservative management with massage and ocular lubrication

- Blepharotomy

Exaggerated postoperative wink

- Careful preoperative workup and discussion with patient or parents

- Revise as necessary

Poor wound healing

- Proper wound care and observation

- Repair as necessary

Bleeding or hematoma formation

- Meticulous hemostasis during surgery

- Return to surgery as necessary

Lagophthalmos

- Expected with frontalis suspension and large levator resections

- Ocular lubrication

Lid crease abnormalities

Entropion

- Aggressive lubrication

- Revision based on underlying cause

Disease-related complications

- Amblyopia

- Can result from anisometropia, astigmatism, strabismus, or occlusion of visual axis

Historical perspective

- In 1880, frontalis suspension introduced by Dransart.

- In 1883, jaw wink was first described by Marcus Gunn.

- In 1965, Beard advocated bilateral frontalis suspension with bilateral levator disabling.

- In 1972, Callahan proposed unilateral levator disabling with bilateral frontalis suspension.

- In 1973, Putterman published the use of a Fasanella-Servat approach on jaw wink.

- In 1980, Bullock discussed the complete extirpation of the levator muscle to the orbital apex.

- In 1982, Dryden, Fleming, and Quickert described the anchoring of the proximal end of the levator muscle to the arcus marginalis.

References and additional resources

References

- Basu AP, Bellis P, Whittaker RG, McKean MC, Devin A. Teaching NeuroImages: alternating ptosis and Marcus Gunn jaw-winking phenomenon with PHOX2B mutation. Neurology. 2012; 79:e153.

- Beard C. A new treatment for severe unilateral congenital ptosis and for ptosis with jaw-winking. Am J Ophthalmol. 1965; 59:252-258.

- Bowyer JD, Sullivan TJ. Management of Marcus Gunn jaw winking synkinesis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004; 20:92-98.

- Callahan A. Correction of unilateral blepharoptosis with bilateral eyelid suspension. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972; 74:321-326.

- Davis G, Chen C, Selva D. Marcus Gunn Syndrome. Eye. 2004; 18:88-90.

- Demirci H, Frueh BR, Nelson CC. Marcus Gunn jaw-winking synkinesis. Ophthalmology. 2010; 117:1447-1452.

- Kersten RC, Bernardini FP, Khouri L, Moin M, Roumeliotis AA, Kulwin DR. Unilateral frontalis sling for the surgical correction of unilateral poor function ptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 21:412-416.

- Khwarg SI, Tarbet KJ, Dortzbach RK, Lucarelli MJ. Management of moderate-to-severe Marcus-Gunn jaw-winking ptosis. Ophthalmology. 1999 Jun;106(6):1191-6.

- Pearce FC, McNab AA, Hardy TG. Marcus Gunn Jaw-Winking Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review and Report of Four Novel Cases. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep/Oct;33(5):325-328.

- Shah G, Khurana D, Das S, Tiple S, Honavar SG. Unilateral Frontalis Suspension With Silicone Sling Without Levator Extirpation in Congenital Ptosis With Marcus Gunn Jaw Winking Synkinesis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020 Jul/Aug;36(4):390-394.

- Singh P, Koka K, Alam MS, Mukherjee B. Management of Marcus Gunn jaw wink syndrome with tarsofrontalis sling vis a vis levator excision and frontalis sling: a comparative study. Orbit. 2023 Feb;42(1):52-58.

- Sobel RK, Allen RC. Incidence of bilateral Marcus Gunn jaw-wink. Ophthal Plast Recon Surg. 2014;30:e54-55.

- Tsai CC, Lin TM, Lai CS, Lin SD. Use of orbicularis oculi muscle flap for severe Marcus Gunn ptosis. Ann Plast Surg. 2002; 48:431-434.

- Wong JF, Theriault JF, Bouzouaya C, Codere F. Marcus Gunn jaw-winking phenomenon: a new supplemental test in the preoperative evaluation. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001; 17:412-418.

Additional Resources

- AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System, 2010-2011.

- AAO, Ophthalmology Monograph 8. Surgery of the Eyelid, Orbit, and Lacrimal System. Vol. 2, 1995, 91-93.

- AAO, Focal Points: Congenital Ptosis. Vol. 19, No. 2, 2001.

- Beard C. In: Ptosis. 3rd ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1981:32-33, 47-49, 113-115, 208.

- Bullock JD. Marcus-Gunn jaw-winking ptosis: classification and surgical management. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1980; 17:375-379.

- Khwarg SI, Tarbet KJ, Dortzbach RK, Lucarelli MJ. Management of moderate-to-severe Marcus-Gunn jaw-winking ptosis. Ophthalmology. 1999; 106:1191-1196.

- Pratt SG, Beyer CK, Johnson CC. The Marcus Gunn phenomenon: a review of 71 cases. Ophthalmology. 1984; 91:27-30.

- Dryden RM, Fleming JC, Quickert MH. Levator transposition and frontalis sling procedure in severe unilateral ptosis and the paradoxically innervated levator. Ophthalmology. 1982; 100:462-464.

- Griepentrog GJ, Diehl NN, Mohney BG. Incidence and demographics of childhood ptosis. Ophthalmology. 2011; 118:1180-1183.

- Patel CK, Anderson RL. History of oculoplastic surgery (1896-1996). Ophthalmology. 1996; 103:s74-84.