Melanoma of the Eyelid

Updated July 2025

Bita Esmaeli, MD; Vivian T. Yin, MD

The etiology and management of periocular cutaneous melanoma is similar to nonocular cutaneous melanoma. It differs from uveal and conjunctival melanoma. Coordination with a multidisciplinary oncology team is usually recommended.

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Overview – malignant transformation of skin melanocytes is most commonly from UV induced DNA damage

- Proliferative signals are activated (i.e., BRAF, KIT oncogenes)

- Tumor suppressor genes become dysregulated and inactivated (Milman, Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013)

- Malignancy may develop de novo or in predisposed lesion such as cellular blue nevus (Nevus of Ota) or dysplastic nevus

- BRAF oncogene – Melanomas arising after intermittent, rather than chronic, UV exposure are more likely to harbor BRAF mutations.

- The RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK–MAP kinase pathway mediates cellular responses to growth signals.

- Three RAF genes code for cytoplasmic serine/threonine kinases that are regulated by RAS binding.

- Activating mutations in BRAF occur in approximately 50% of melanomas. Other members of the Raf family are ARAF and CRAF

- All BRAF mutations are within the kinase domain, with a single substitution (V599E) accounting for 80%.

- Activated BRAF proteins have elevated kinase activity and RAS function is not required for the growth of cancer cell lines with the V599E mutation.

- Other common BRAF mutations in melanoma, found in the same codon, are V600K (about 16% of mutations in melanoma) and V600D/R.

- These less common variants are found at slightly higher rates in melanomas arising in older patients (Davies, Bignell 2002).

- KIT oncogene – melanomas in skin with chronic sun induced damage infrequently have mutations in BRAF and NRAS but uniquely harbor activating mutations in KIT (Friedlander, Hodi 2010).

- The KIT proto-oncogene encodes a tyrosine-kinase transmembrane receptor in the MAPK pathway that regulates cellular proliferation (Takata, 2013).

- Only 10-20% harbor KIT activation.

- Over 20 KIT mutations have been identified in melanoma, most are point mutations.

- Most common is leucine to proline substitution at codon 576 of exon 11 which comprises one third of KIT mutations in melanoma (Woodman, Davies 2010).

Epidemiology

- Accounts for less than 1% of eyelid malignancies (Cook, Ophthalmology 1999)

- More common in older individuals, mean age at presentation in the 6th decade (Esmaeli, OPRS 2000)

- Rarely occurs in non-Caucasians (Garbe, Clin Dermatol 2009)

- Increasing incidence for melanoma overall by 3 fold from 1970s to beginning of 2000 (Garbe, Clin Dermatol 2009)

- Increasing incidence in each of the past four decades (Kauffman, Surg Clin North Am 2014)

- Equal gender distribution (Esmaeli, OPRS 2000)

- Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in the United States (incidence = 76,100 cases/year, 9,710 deaths in 2014) (American Cancer Society 2015; SEER Stat Fact Sheet 2015).

History

- History of other skin cancer and cell type

- Characteristics of lesion to inquire include duration, growth, bleeding

- History of sun or UV exposure (tanning bed use)

- Immune suppression

- Light skin/hair (Milman, Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013)

- Genetic syndromes (xeroderma pigmentosum, Wiskott-Aldrich)

Clinical features

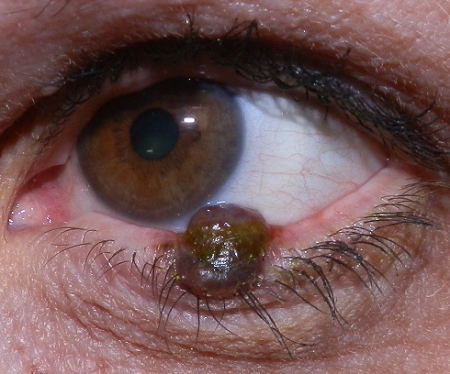

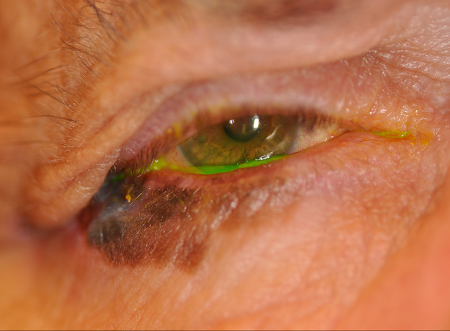

- Clinical features indicative of malignancy include lid margin destruction, ulceration, madarosis, irregular boarder, heterogeneous pigmentation (Figures 1 and 2)

- Rarely can present without pigmentation (i.e., amelanotic melanoma)

Figure 1. Eyelid melanoma. Image courtesy Brett Davies, MD.

Figure 2. Eyelid melanoma. Image courtesy Jennifer Sivak, MD.

Testing

- Incisional biopsy of the melanocytic lesion and examination under paraffin embedded tissue is gold standard for diagnosis

- High risk histological features include: Breslow thickness, ulceration, mitotic figures, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, satellitosis and regression

- Depth of invasion is the single best predictor of survival (Kauffman, Surg Clin North Am 2014)

- High dermal mitotic rate portends decreased survival (Mathew, Semin Oncol 2012; Sondak, Ann Surg Oncol 2004)

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

- AJCC 7th edition Cancer Staging Manual defines TNM categories for melanoma

- T-stage based on Breslow thickness and ulceration

- Nodal category refers to nodal metastasis:

- Regional nodal basin at risk for metastasis include the parotid, submandibular, and cervical nodes

- Evaluation may entail palpation, imaging studies such as ultrasound or CT guided fine needle aspiration biopsy for suspicious nodes

- Alternatively, sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy can be performed for high risk lesions

- Baseline CT of chest/abdomen/pelvis and MRI of brain may also be appropriate for lesions greater than 2 mm thickness or with histological ulceration.

- These tests should be repeated periodically in high risk patients or in patients with positive SLNs

- When clinical exam suspicious for orbital invasion, orbital CT or MRI will assist in surgical planning.

Risk factors

- UV (sun) exposure

- Fair skinned, Fitzpatrick skin type I-III

- Genetic predisposition (dysplastic nevus syndrome)

- Lesions predisposed to transformation: Nevus of Ota or cellular blue nevus or dysplastic nevus

- Genetic syndromes

Differential diagnosis

- Lentigo maligna

- Nevus

- Lentigo senilis

- Pigmented basal cell carcinoma

- Pigmented seborrheic keratosis

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Melanoma greater than T2b AJCC 7th edition staging is correlated with shorter time to progression and nodal and distant metastasis

- Overall rate of lymph node metastasis is approximately 10% and distant metastasis is can occur up to 7.7%

- Breslow thickness and Clark level are independent predictors of survival (Esmaeli, OPRS 2000)

- In one recent study, survival outcomes were significantly influenced by age, tumor stage, socioeconomic status, and facility characteristics (high-volume centers confer a survival advantage) (Robbins 2025)

Local treatment

- Wide local excision, 5mm margin recommended, with delayed reconstruction after margins status is confirmed on paraffin embedded (permanent) processing

- Some surgeons advocate 10 mm margins for tumors with Breslow thickness of 2 mm or greater (Esmaeli, OPRS 2003; Rene, Eye 2013)

- Alternative tissue processing described use of immunochemical staining on frozen section not yet validated in large scale study

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered for patients with thick melanoma

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

- Indications: Eyelid melanoma with Breslow thickness > 2 mm (Savar, Ophthalmology 2009) or ulceration on histopathology

- Treatments for a positive SLN: Complete neck dissection, possible radiation if more than 2 positive nodes or extracapsular extension; and consider for trials for Stage III melanoma.

Radiation

- High dose adjuvant radiation may be used in desmoplastic melanoma after surgery

- Radiation therapy is considered in the case of positive nodes on neck dissection after a positive sentinel lymph node is identified

- Used for palliative therapy when metastasis to brain, bone or lymph nodes

Treatment of systemic metastasis

- Traditionally cytotoxic chemotherapy, such as carboplatin, paclitaxel, and dacarbazine wereused for metastatic disease

- Biochemotherapy, interferon or interleukin-2, may have higher efficacy but higher toxicity

- BRAF inhibitors such as vemurafenib and debrafenib and MEK inhibitors such as trametinib are approved for use in surgically unresectable or metastatic melanoma

- Immunotherapy has been used for locally advanced (particularly when the orbit is involved) or metastatic disease (Wladis 2025)

Other management considerations

- Molecular testing for BRAF

- Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes collection for experimental immunotherapy in patients with metastasis

Local recurrence

- Rate of local recurrence after complete excision reported from less than 1% up to 25% (Chan, Ophthalmology 2007)

- Patient should be followed every 3 months for the first year, followed by every 6 months the second year, then yearly for 5 years

- Palpation for neck lymphadenopathy and inspection of all four eyelids, including eversion of all four lids to examine the tarsal conjunctival, should be performed on all follow-ups

- Investigation with neck ultrasound or CT of the neck and CT chest/abdomen/pelvis should be utilized for patients with high risk melanoma (Breslow > 1.5mm with ulceration) or if palpable neck lymphadenopathy

- Nodal metastasis found during the follow-up is treated as described above for patients with a positive SLN.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Loss of vital ocular adnexal structures such as lacrimal drainage system

- Prevention is not always possible, but in case of partial loss of canaliculus, primary reconstruction using either mono-canalicular or bi-canalicular stent may eliminate need for further surgery

- Conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy with Jones tube if significant loss of both canaliculi may be necessary but should be delayed until final pathology is available

- Lagophthalmos from ectropion can be managed with lateral tarsal strip procedure or in the case of cicatricial ectropion, full-thickness skin graft may be needed

- Diplopia may result from direct damage or cicatricial changes when extensive orbital dissection is needed for tumor excision

- Facial nerve paralysis as a result of lymph node dissection can be managed with aggressive lubrication in mild cases

- Surgical management should include gold weight implant, ectropion repair with lateral tarsal strip and tarsorrhaphy

- Loss of the globe due to extensive, multiple recurrent disease is rare but may not be avoidable when there is significant loss of periocular soft tissue

Disease-related complications

- Local tumor invasion of orbit can lead to diplopia, vision loss (orbital compartment syndrome or direct tumor compression of optic nerve)

- Local tumor invasion of lacrimal drainage system can lead to symptoms of epiphora

- Local tumor invasion of trigeminal nerves can cause facial pain or numbness

- Metastasis – in-transit, regional/nodal, distant

References and additional resources

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network, www.nccn.org

- National Cancer Institute, www.cancer.gov

- AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 4: Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors; Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids and Lacrimal System, 2013-2014.

- American Cancer Society. “What are the key statistics about melanoma?”. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/skincancer-melanoma/detailedguide/melanoma-skin-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed April 29, 2015.

- Chan FM, O’Donnell BA, Whitehead K, Ryman W, Sullivan TJ. Treatment and outcomes of malignant melanoma of the eyelid: A review of 29 cases in Australia. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(1):187-92

- Cook Jr BE and Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in olmsted county, minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(4):746-50.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002;417:949-54

- Esmaeli B. Ophthalmic Oncology. M.D. Anderson Solid Tumor Oncology Seires. New York: Springer, 2011.

- Esmaeli B, Wang B, Deavers M, Gillenwater A, Goepfert H, Diaz E, Eicher S. Prognostic factors for survival in malignant melanoma of the eyelid skin. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;16(4):250-7.

- Esmaeli B, Youssef A, Naderi A, et al. Margins of excision for cutaneous melanoma of the eyelid skin: the Collaborative Eyelid Skin Melanoma Group Report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 19: 96–101, 2003.

- Friedlander P, Hodi FS: Advances in targeted therapy for melanoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2010; 8:619-27.

- Garbe C and Leiter U. Melanoma epidemiology and trends. Clin Dermatol. 2009; 27(1):3-9.

- Kauffman RM and Chen SL. Workup and staging of malignant melanoma. Surg Clin North Am. 94: 963-72, 2014.

- Mathew R., and Messina J.L.: Recent advances in pathologic evaluation and reporting of melanoma. Semin Oncol. 39: 184-191, 2012.

- Milman T and McCormick SA. The molecular genetics of eyelid tumors: Recent advances and future directions. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 251: 419-33, 2013.

- Rene C. Oculoplastic aspects of ocular oncology. Eye, 27: 199-207, 2013.

- Robbins JO, Huck NA, Khosravi P, et al. Trends in demographic, clinical, socioeconomic, and facility-specific factors linked to eyelid melanoma survival: a national cancer database analysis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. Published online January 6, 2025.

- Savar A, Ross MI, Prieto VG, Ivan D, Kim S, Esmaeli B. 2009. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for ocular adnexal melanoma: Experience in 30 patients. Ophthalmology 116(11):2217-23.

- SEER Stat Fact Sheet: Melanoma. From the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html. Accessed April 29, 2015.

- Sondak V.K., Taylor J.M., Sabel M.S., et al: Mitotic rate and younger age are predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity: lessons learned from a generation of a probabilistic model. Ann Surg Oncol. 11: 247-258, 2004.

- Takata M: Identifying BRAF and KIT mutations in melanoma. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2013; 8:171.

- Wladis EJ, Rothschild MI, Bohnak CE, Adam AP. New therapies for unresectable or metastatic cutaneous eyelid and orbital melanoma. Orbit. 2025;44(1):137-143.

- Woodman SE, Davies MA. Targeting KIT in melanoma: a paradigm of molecular medicine and targeted therapeutics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010; 80(5): 568–574.

- Yin V, Esmaeli B. Eyelid tumors: Sentinel Lymph Node Assessment and Biopsy for Eyelid and Conjunctival Malignancies. In: Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology – Eyelid and Conjunctival Tumours. 2nd. Ed(s) Pe’er J Singh AD. Springer 111-124, 2014.

- Yin VT, Warneke CL, Merritt HA, Esmaeli B. Number of excisions required to obtain clear margins and prognostic value of AJCC T category for patients with eyelid melanoma. Br J Ophthalmol. In Press.

Financial disclosures

Financial Disclosures

Reviewers

Victoria North – No disclosures