Orbital Meningocele, Encephalocele, and Meningoencephalocele

Updated May 2024

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Congenital bony defect in skull base

- Traditionally classified with neural tube defects (NTD), but embryogenesis can occur after closure of neural tube.

- Most cases sporadic

- Exact cause unknown

- Can be isolated or associated with other malformations.

- Agenesis of corpus callosum, Dandy-Walker malformation, hydrocephalus, holoprosencephaly (Bersani, OPRS 2006)

- Traumatic skull base or orbital roof fracture

- Relatively small (2–4 mm) roof fractures can cause delayed encephaloceles in children (Cayli, Pediatr Neurosurg 2003).

- Orbital or skull base surgery

- Tumor resection

- LeFort III osteotomy (Ridgway, J Craniofac Surg 2011)

- Medial orbital decompression (Murchison, OPRS 2012)

- Malignant or inflammatory conditions of bone, meninges, or sinuses (e.g., eosinophilic granuloma, natural killer T-cell lymphoma, cocaine abuse)

- Gorham-Stout syndrome (“disappearing bone disease”) (Krohel, AJO 2002)

- Rare idiopathic osteolytic condition, often affects skull and face

Epidemiology

- Congenital

- Worldwide incidence of encephalocele (all types) 1 in 5000 births; lower in North America: 1 in 10,000–15,000 (Sever, Teratology 1982)

- Posterior (occipital) location predominates in North America, Europe, Australia, Japan (Hunt, Plast Reconstr Surg 2003).

- Anterior more common in Southeast Asia and Russia

- No familial pattern

- Traumatic: Typically children or young male adults

History

- Congenital cases usually apparent at or shortly after birth

- Associated with numerous craniofacial anomalies and clefting syndromes

- Undiagnosed cases can sometimes present with meningitis, CSF leak, seizures, or nasal airway obstruction.

- Acquired: history of craniofacial trauma, orbital or skull base surgery

Clinical features

Herniation of intracranial tissue into orbit:

- Meningocele: meninges

- Encephalocele: brain tissue (often disorganized or infarcted)

- Meningoencephalocele: meninges and brain tissue

Locations:

- Congenital

- Sincipital

- Frontoethmoidal: majority of cases involving orbit

- Nasofrontal

- Nasoethmoidal

- Naso-orbital

- Interfrontal

- Cleft-associated

- Basal

- Transethmoidal

- Sphenoethmoidal

- Trans-sphenoidal

- Spheno-orbital

- Convexity

- Frontal

- Parietal

- Temporal

- Occipital

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1): sphenoid greater wing

- Fracture or surgery: orbital roof and/or medial wall

Orbital mass effect causes proptosis and/or downward/medial displacement of globe:

- Straining and crying might result in increased size of mass

- Pulsation of globe or mass

- Vision loss might result from strabismus or amblyopia (meridional or occlusional)

Herniated tissue can cause subcutaneous bulging or even peduculated mass in nasal or medial canthal region (Figure 1):

- Location typically above medial canthal tendon

Figure 1. Congenital bilateral frontoethmoidal meningoencephalocele.

Facial findings:

- Hypertelorism

- Elongation of face

- Nasal airway obstruction

- Dental malocclusion

Associated intracranial abnormalities:

- Hydrocephalus

- Microcephaly

- Cerebral dysplasia

- Agenesis of corpus callosum

Sometimes associated with other ocular anomalies:

- Morning glory syndrome

- Colobomas

- Microphthalmos

- Anophthalmos

- Cryptophthalmos

- Corneal clouding

- Nasolacrimal duct obstruction

Testing

- Neuroimaging

- CT scan is best modality to demonstrate bony defect.

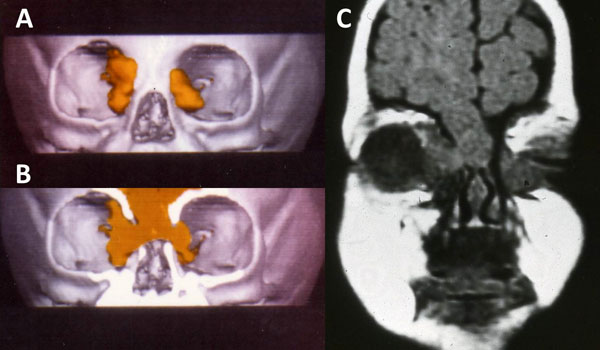

- 3D reconstruction can be helpful for operative planning (Figure 2).

- MRI provides excellent soft-tissue resolution.

Figure 2. Neuroimaging of patient in figure 1. A. 3-dimensional orbital CT reconstruction showing bilateral orbital roof and medial wall defects with herniated cranial tissue (yellow). B. Same study with coronal cut showing communication of brain with orbit. C. Orbital MRI, coronal view.

Risk factors

- Possible congenital risk factors

- Consanguinity

- Advanced paternal age

- Maternal

- Infection: toxoplasmosis, rubella, CMV

- Medications: valproate

- Vitamin deficiency (e.g., folate)

- Teratogens

- Maternal hyperthermia or diabetes

- History of craniofacial trauma or surgery

Differential diagnosis

- Lacrimal sac pathology (usually presents as mass below medial canthal tendon)

- Dacryocystocele

- Dacryocystitis

- Lacrimal sac tumor

- Orbital tumor

- Hemangioma

- Dermoid cyst

- Lymphangioma

- Rhabdomyosarcoma

- Teratoma

- Orbital infection/inflammation

- Orbital cellulitis

- Subperiosteal abscess

- Idiopathic orbital inflammation

- Carotid-cavernous fistula (pulsatile proptosis)

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Congenital cases typically present in early infancy or childhood and are usually fairly static.

- Visual prognosis depends on severity and amount of herniation affecting globe position.

- Facial development abnormally impacted

- Early treatment indicated to facilitate normal orbitofacial development

- Post-traumatic cases can present immediately or delayed.

- Immediate brain herniation frequently portends poor neurological prognosis due to severity of trauma.

- Roof fractures can progressively enlarge (“growing orbital roof fracture”) (Alsuhaibani, OPRS 2011).

- Usually occurs in children due to skull growth

Medical therapy

- Manage amblyopia if present

- Observation appropriate for small asymptomatic lesions

Surgery

Congenital — craniofacial reconstruction:

- Individualized based on location, size, and presence of bony/soft tissue deformities

- Multidisciplinary approach extremely useful: neurosurgery, facial plastic surgery, otolaryngology, oculoplastic surgery

- Aspects of reconstruction

- Urgent closure of open skin defects

- Resection of herniated brain and/or meninges

- Repair of bony defect

- Reconstruction of bony deformities

- Watertight dural closure

- Soft-tissue reconstruction

- Strategies for reconstruction

- Traditionally staged

- Craniotomy to reduce herniation and repair bone/dural defect

- Facial plastic surgery to correct soft tissue deformity

- Single-stage operation now widely accepted (David, Br J Plast Surg 1984)

- Surgical technique

- Frontal craniotomy through bicoronal incision

- Cerebral herniation reduced as much as possible, disorganized parenchyma and/or meninges resected

- Intraorbital herniation can be addressed through separate orbitotomy incision if desired (transconjunctival, transcaruncular, or upper-lid crease).

- Bony defect repaired

- Inner table of calvarium, rib bone, titanium mesh, porous polyethylene, etc.

- Dural defect repaired primarily or with graft

- Temporalis fascia, porcine, or cadaveric dermis, pericranial flap, etc.

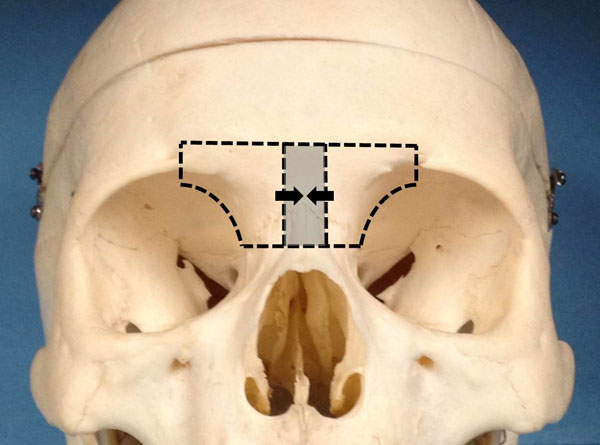

- If hypertelorism present, osteotomies of the frontal bar and naso-orbito-ethmoid complexes performed to facilitate bony reconstruction (Figure 3)

- Facial reconstruction

- Perinasal incision (lazy S or inverted Y) to excise redundant skin

- If mass is small- to medium-sized, redundant skin can be left to contract spontaneously without need for excision.

- Medial canthopexy to correct telecanthus (see Lateral and Medial Canthopexy)

- Chula technique (Mahatumarat, J Craniofac Surg 1991)

- Bicoronal incision without frontal craniotomy

- Fronto-orbito-nasal osteotomy provides access to defect in addition to facilitating correction of hypertelorism.

Figure 3. Medial orbital and frontal bar osteotomies for correction of hypertelorism. Shaded area represents bone to be removed.

Traumatic/postsurgical:

- Subfrontal craniotomy approach generally used to reposition intracranial contents and repair dural/bony defect

- Numerous materials available: titanium, porous polyethylene, autologous bone graft, etc.

- Concomitant frontal sinus fractures often present and can require treatment

- Endoscopic approach can be used to repair

- Congenital encephaloceles of ethmoid roof and/or cribriform plate without orbital involvement (Woodworth, Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004)

- Meningoencephalocele following medial orbital decompression (Schaberg, Orbit 2011)

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Neurosurgical complications

- Cerebrospinal fluid leak

- Hydrocephalus

- Infection, meningitis

- Prevention with intra- and postoperative broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Seizures

- Death

- Ophthalmic complications

- Orbital hemorrhage, globe/optic nerve damage, ischemia

- Globe malposition

- Strabismus

- Management of amblyopia

- Strabismus surgery

- Facial scarring, persistent orbitofacial deformity

Disease-related complications

- Neurological complications arising from intracranial abnormalities

- Developmental delay, cerebral palsy, meningitis, seizure, death

- NF1: possible plexiform neurofibromas, optic nerve gliomas, glaucoma

- Trauma: associated craniofacial and ocular injuries

- Risk of traumatic optic neuropathy with orbital roof fractures

- Frontal sinus fractures at risk for infectious complications

References and additional resources

- Agthong S, Wiwanitkit V. Encephalomeningocele over 10 years in Thailand: a case series. BMC Neurol 2002;2:3.

- Albert L, DeMattia JA. Cocaine-induced encephalocele: case report and literature review. Neurosurgery 2011;68:e263-266.

- Alsuhaibani AH, Hitchon PW, Smoker WRK, et al. Orbital roof encephalocele mimicking a destructive neoplasm. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;27:e121-123.

- Andrews BT, Meara JG. Reconstruction of frontoethmoidal encephalocele defects. Atlas Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am 2010;18:129-138.

- Antonelli V, Cremonini AM, Campobassi A, et al. Traumatic encephalocele related to orbital roof fractures: report of six cases and literature review. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:117-125.

- Arshad AR, Selvapragasam T. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele: treatment and outcome. J Craniofac Surg 2008;19:175-183.

- Bersani TA, Cecchi LM. Resection of anterior orbital meningoencephalocele in a newborn infant. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;22:391-393.

- Cantatore S, Crisalfi A, Guaraldi N, et al. Recurrent pneumococcal meningitis in a child with transethmoidal encephalocele: a case report and review of the literature. Minerva Pediatr 2011;63:119-124.

- Cayli SR, Kocak A, Alkan A, et al. Intraorbital encephalocele: an important complication of orbital roof fractures in pediatric patients. Pediatr Neurosurg 2003;39:240-245.

- David DJ, Sheffield L, Simpson D, White J. Fronto-ethmoidal meningoencephaloceles: morphology and treatment. Br J Plast Surg. 1984;37:271-284.

- Dutton JJ, Sines DT, Elner VM. Orbital tumors. In Black EH, Nesi FA, Calvano CJ, et al ed., Smith and Nesi’s Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 3rd Ed. New York: Springer, 2012.

- Emsen IM, Benlier E. A new approach on reconstruction of encephalomeningocele assisted with Medpor. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:537-541.

- Garrity JA, Henderson JW, Cameron JD. Henderson’s Orbital Tumors, 4th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2007.

- Hunt JA, Hobar PC. Common craniofacial anomalies: facial clefts and encephaloceles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:606-614.

- Khan A, Lapin A, Eisenman DJ. Use of titanium mesh for middle cranial fossa skull base reconstruction. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2014;75:104-109.

- Krohel GB, Freedman K, Peters GB, Popp AJ. Gorham disease of the orbit. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:729-30.

- Kumar A, Helling E, Guenther D, et al. Correction of frontonasoethmoidal encephalocele: the HULA procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:661-669.

- Mahatumarat C, Taecholarn C, Charoonsmith T. One-stage extracranial repair and reconstruction for frontoethmoidal encephalonmeningocele: a new simple technique. J Craniofac Surg. 1991;2:127-133.

- Metzinger SE, Guerra AB, Garcia RE. Frontal sinus fractures: management guidelines. Facial Plast Surg. 2005;212:199-206.

- Murchison AP, Schaberg M, Rosen MR, et al. Large meningoencephalocele after orbital decompression. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:e64-65.

- Ridgway EB, Robson CD, Padwa BL, et al. Meningoencephalocele and other dural disruptions: complications of LeFort III midfacial osteotomies and distraction. J Craniofac Surg 2011;22:182-186.

- Rojvachiranonda N, David DJ, Moore MH, Cole J. Frontoethmoidal encephalomeningocele: new morphological findings and a new classification. J Craniofac Surg 2003;14:47-58.

- Rojvachiranonda N, Mahatumarat C, Taecholarn C. Correction of the frontoethmoidal encephalomeningocele with minimal facial incision: modified Chula technique. J Craniofac Surg 2006;17:353-357.

- Schaberg M, Murchison AP, Rosen MR, et al. Transorbital and transnasal endoscopic repair of a meningoencephalocele. Orbit 2011;30:221-225.

- Sever LE, Sanders M, Monsen R. An epidemiologic study of neural tube defects in Los Angeles County, I: prevalence at birth based on multiple sources of case ascertainment. Teratology 1982;25:315-321.

- Woodworth BA, Schlosser RJ, Faust RA, Bolger WE. Evolutions in the management of congenital intranasal skull base defects. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;130:1283-1288.