Necrotizing Fasciitis

Updated July 2024

Vikram Durairaj, MD; Brett Davies, MD

This devastating infection was once managed with wide surgical debridement but advances now frequently permit medical therapy with delayed reconstruction for cervicofacial cases.

Establishing the diagnosis

Etiology

- Pyogenic bacterial infection, usually by Streptococcus pyogenes

- Synergistic infection by facultative anaerobes such as Enterobacteriaceae or anaerobes in 35%

- Rare association with Clostridium sordellii in intravenous (IV) drug abuse

- Fungal etiologies such as Aspergillus and Candida species have also been reported in the periocular area (Rath, OPRS 2009)

- Infection leads to release of pro-inflammatory markers from helper T cells, which can lead to further tissue damage

- Interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-6, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), TNF-β, and Interferon γ (Mutamba, Eye 2013)

Epidemiology

- Uncommon severe soft tissue infection that most commonly affects the abdominal wall, perineum, and extremities

- Cervicofacial involvement in less than 10% of cases (Ord, Oral Dis 2009)

- More frequent in setting of alcoholism or diabetes mellitus

- Often associated with minor skin trauma, insect bite, or surgery

History

- Develops 2–4 days after local trauma with rapid progression, pain and fever

Clinical features

- Stages

- Stage 1: localized edema, fever, and pain out of proportion

- Stage 2: tissue ischemia due to thrombosis of the vasculature and clinically the skin starts to show small blisters.

- Stage 3: complete blockage of the blood supply to the fascia and loss of sensation to that area, patchy discoloration of the overlying skin, and gas production seen on imaging.

- Skin progresses from red and tensely swollen to painful necrosis (Figure 1)

- Anesthesia can appear early with damage to sensory nerves

- Early clinical appearance similar to cellulitis

- Skin becomes dusky in 1–2 days with apparent necrosis in 4–5 days and sloughing in 8–10 days

- Hemorrhagic bullae can be present

- Marked leukocytosis (>30,000/mm3)

- Relative sparing of the underlying muscle

- Approximately 30% mortality in all body sites. In the periocular area, mortality rate is lower (14.4%) (Lazzeri, OPRS 2010)

Testing

- Culture, gram stain, and sensitivity of wound edges, debrided tissue or fluid in bullae

- Frozen section pathology intraoperatively to detect necrosis

- Blood cultures and systemic evaluation as indicated

- CT useful to demonstrate involvement of fascia planes

Testing for staging, fundamental impairment

It helps to mark the demarcation line between healthy tissue and affected tissue to monitor for progression

Figure 1. Necrotizing fasciitis of the left upper eyelid.

Risk factors

- Immunocompromised

- Diabetes

- ETOH abuse

- History of local trauma

- However, immunosuppression may not correlate with visual outcomes, survival, and globe preservation

Differential diagnosis

- Nonfasciitis skin infections such as

- MRSA

- Erysipelas

- Gas gangrene

- Streptococcal myositis

- Progressive bacterial synergistic gangrene

- Dermatomyositis can mimic early infection

- Noninfectious necrotizing processes

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

- Spider bites

- Mechanical, chemical, and electrical trauma

- Postoperative subcutaneous emphysema can mimic necrotizing fasciitis (Ghosheh, OPRS 2005)

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Natural history

- Rapid progression over hours to days

- In the periocular area, can advance into the orbit

- Predictors of severity of periorbital necrotizing fasciitis (Rothschild, Orbit, 2022)

- Increased age at presentation correlated with worse presentation and final visual acuity, needing increased number of debridements

- Worse visual acuity correlated with need for increased number of debridements

Medical therapy

- Cultures

- Initial antibiotic coverage

- Coverage for streptococci, staphylococci, Enterobacteriaceae, and anaerobes

- Ampicillin/sulbactam (Unasyn), Piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn), or Gentamicin with clindamycin or metronidazole intravenously in consultation with infectious disease consultant (Morgan, Curr Inf Dis Rep 2011)

- Tailor antibiotics to culture results and sensitivities

- Antifungals if indicated by cultures

- Correct underlying immunodeficiency if present

- Correct underlying metabolic imbalance

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be avoided as they can accelerate renal failure in these patients

- Aggressive fluid resuscitation in patients with septic shock

Surgery

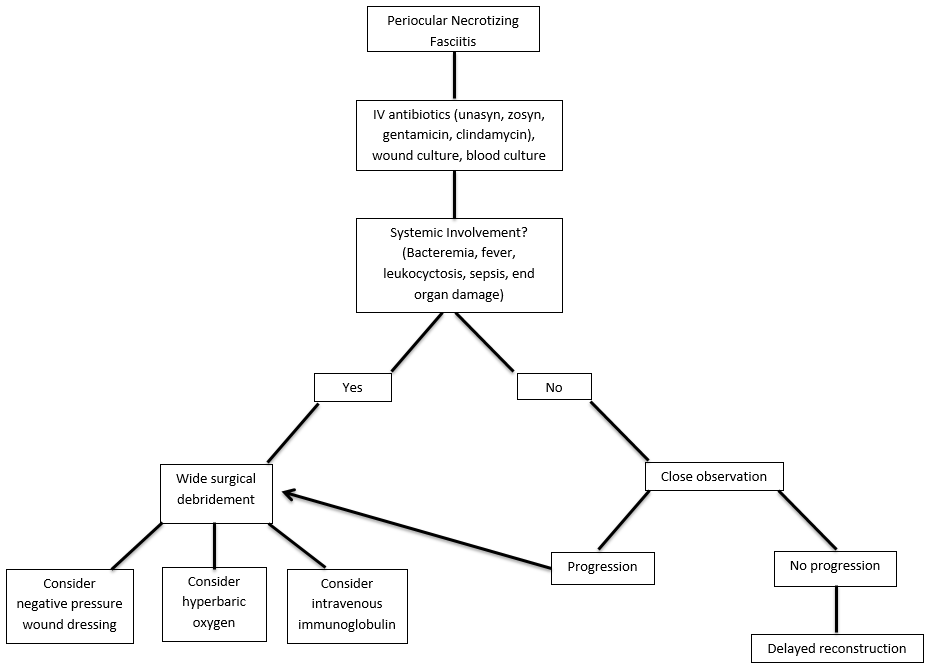

Considerations for debridement versus observation (Figure 2):

- Early, wide surgical debridement recommended by most authors. Excision should continue until healthy, well perfused tissue is identified (Marshall, Ophthalmology 1997; Tambe, Eye 2012; Aakalu, OPRS 2009)

- More conservative medical management with delayed surgical debridement can be considered in cases limited to the periocular area without systemic involvement. In these cases, the devitalized but sterile tissue can remain in place until secondary reconstruction is planned weeks to months later (Mutamba, Eye 2013)

- With conservative management, it is imperative to ensure tissue destruction is not advancing. This can be accomplished by marking the area of necrosis, and monitoring closely for progression

- If confined to the eyelids, secondary reconstruction might not be necessary at all (Luksich, Ophthalmology 2002)

Figure 2. Algorithm for the management of periocular necrotizing fasciitis.

- Modified wound closures have been described when technically feasible where the skin is closed with sutures placed 4 mm apart using 6-0 polypropylene of cat gut sutures. Gauze soaked in iodine is packed between each suture and changed every 2 days. After 2-3 dressing changes, most of the wound has granulated but additional sutures may be required (Wladis, OPRS, 2015).

- Exenteration may be required, especially more common in patients with a history of immunosuppression (Wladis, OPRS, 2015)

Other management options

- Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) at 75 mm Hg can expedite wound healing and improve skin graft survival. Has been shown in case report to be safe in the periocular area, with no long-term effect on vision or intraocular pressure (IOP). IOP should be monitored while on NPWT (Semlacher, OPRS 2012)

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has been shown to decrease mortality and increase tissue viability in case series (Lazzeri, OPRS 2010; Brown, Am J Surg 1994)

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has been found beneficial in case reports and small cases series (Morgan, Curr Inf Dis Rep 2011; Aakalu, OPRS 2009)

Common treatment responses, follow-up strategies

- Mortality can be as high as 60%, depending on the causative organism and location of the infection

- Tissue loss due to infection or debridement might require secondary reconstruction with skin grafts, advancement flaps, or other reconstruction techniques (Tambe, Eye 2012)

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Antibiotic-resistant bacteria

- Determined empirically or by sensitivities on culture and sensitivity

- Appropriate modification of therapy in consultation with infectious disease

- Tissue loss due to excessive debridement

Disease-related complications

- Tissue loss

- Permanent vision loss and/or motility deficits with orbital involvement

- Metastatic spread to other body sites

- Sepsis with hypotension, renal failure, and death

Historical perspective

- The term “necrotizing fasciitis” was first used by Wilson in 1952 to describe the most consistent feature of the infection, necrosis of the fascia and subcutaneous tissue with relative sparing of the underlying muscle

- In the past, wide surgical debridement was the standard of care for every patient with necrotizing fasciitis. We now have several studies that show that certain patients can be managed medically only, with delayed reconstruction. See discussion above

References and additional resources

- AAO, Basic and Clinical Science Course. Section 7: Orbit, Eyelids and Lacrimal System, 2010-11

- Aakalu VK, Sajja K, Cook JL, et al. Group A streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis of the eyelids and face managed with debridement and adjunctive intravenous immunoglobulin. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Jul-Aug;25(4):332-4

- Brown DR, Davis NL, Lepawsky M, et al. A multicenter review of the treatment of major truncal necrotizing infections with and without hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Am J Surg 1994;167:485-9

- Ghosheh FR, Kathuria SS. Massive subcutaneous emphysema mimicking necrotizing fasciitis after dacryocystorhinosomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005 Sep;21(5):389-91

- Kronish JW, McLeish WM. Eyelid necrosis and periorbital necrotizing fasciitis. Ophthalmology 1991 Jan;98:92-98

- Lazzeri D, Lazzeri S, Figus M, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as further adjunctive therapy in the treatment of periorbital necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A streptococcus. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010 Nov-Dec;26(6):504-5

- Luksich JA, Holds JB, Hartstein ME. Conservative management of necrotizing fasciitis of the eyelids. Ophthalmology 2002 Nov;109(11):2118-22

- Marshall DH, Jordan DR, Gilberg SM, et al. Periocular necrotizing fasciitis: a review of five cases. Ophthalmology 1997;104:1857-62

- Morgan MS. Recent advances in the treatment of necrotizing fasciitis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2011;13:461-9

- Mutamba A, Verity DH, Rose GE. ‘Stalled’ periocular necrotising fasciitis: early effective treatment or host genetic determinants? Eye (Lond). 2013 Mar;27(3):432-7

- Ord R, Coletti D. Cervico-facial necrotising fasciitis. Oral Dis. 2009; 15: 133–141

- Rath S, Kar S, Sahu SK, et al. Fugal periorbital necrotizing fasciitis in an immunocompetent adult. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Jul-Aug;25(4):334-5

- Rothschild MI, et al. Predicting severity of periorbital necrotizing fasciitis. Orbit, 2022; June 10: 1-5

- Semlacher RA, Taylor EJ, Golas L, et al. Safety of negative-pressure wound therapy over ocular structures. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012 Jul-Aug;28(4):e98-101

- Tambe K, Tripathi A, Burns J, et al. Multidisciplinary management of periocular necrotizing fasciitis: a series of 11 patients. Eye 2012;26:463-7

- Wladis EJ. Modified wound closure technique in periorbital necrotizing fasciitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 May-Jun;31(3):242-4

- Wladis EJ, Levin F, Shinder R. Clinical Parameters and Outcomes in Periorbital Necrotizing Fasciitis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov-Dec;31(6):467-9

- Wladis EJ. Periorbital necrotizing fasciitis. Surv Ophthalmol, 2022; 67:1547-1552