Nonsurgical Management of Thyroid Eye Disease

Updated May 2024

Introduction

- The nonsurgical management of thyroid eye disease (TED) is punctuated by the self-limited nature of the process.

- Mostly short term treatment

- Concurrently manage thyroidopathy

- Management by endocrinologist

- May impact the orbital disease

- Observation for mild, inactive disease

- Prevention of progression is primary goal

- Symptomatic relief is secondary goal

- Non-medical reversal is offered in concert with surgery

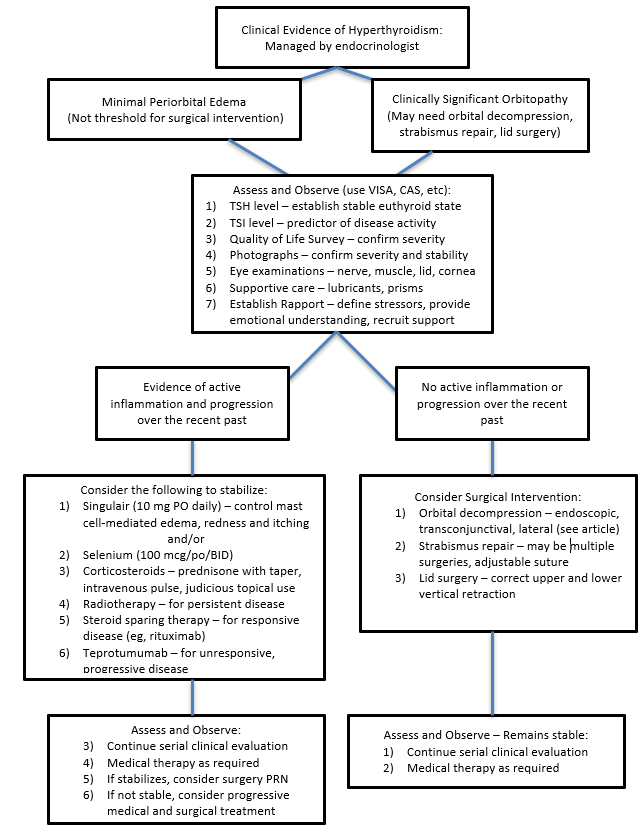

- There are many options but there is no consensus on the best order in which they should be used. Clinical judgment and patient preferences dictate individualized care within the guidelines of current published research. See Figure 1 for a simplified flowchart to illustrate one suggested strategy for management of patients with TED.

Figure 1. Simplified Approach to Thyroid Eye Disease With Clinical Hyperthyroidism

Smokling and TED

- Among the most valuable tools in limiting TED is cessation of smoking.

- Smoking is a risk factor for ophthalmopathy, not as much for thyroidopathy.

- 53 of 85 TED patients (62%) were smokers compared with 17 of 62 (23%) patients with Graves thyroidopathy alone (Shine, 1990).

- 81% of patients with TED and thyroidopathy were smokers compared with 56% of patients with Graves hyperthyroidism alone (Prummel, 1993).

- Control groups of non-Graves, non-TED patients in this era had a 20-35% prevalence of smokers.

- Quantity correlates with severity of disease.

- Pack year history = 1 pack of 20 cigarettes daily x number of years smoked.

- Severe TED correlated with > 20 pack year history.

- In Shine (1990) 21 of 40 patients with severe TED had a >20 pack year history; only 4 of 19 with mild disease had a similar smoking history.

- Smoking correlates with restrictive myopathy more than proptosis.

- Of 124 TED patients, 83% with restrictive myopathy were smokers compared with 63% without restrictive myopathy (Nunery, 1993).

- A higher percentage of smokers than non-smokers (26% vs. 14%, respectively) require strabismus repair (Rajendram, 2011).

- Smoking cessation may decrease incidence and severity of TED.

- Among 253 Graves hyperthyroidism patients without ophthalmopathy who were followed for 1 year after recognition of disease with no change in smoking habits, 49% of active smokers developed proptosis vs. 16%-18% of former and never smokers developed disease (Pfeilschifter, 1996).

- Onset of diplopia was in 28% of smokers, 16% of former smokers, and 9% of never smokers.

- Smoking reduction is modestly beneficial.

- Stratified by degree of smoking:

- >20 cigarettes = 62% incidence of proptosis at one year

- 11–20 cigarettes/day = 59% incidence

- <11 cigarettes = 37%

- Smoking slows blood flow.

- In 51 orbits, smokers had lower flow velocity in superior ophthalmic vein.

- Increases congestion and proptosis (Sadeghi-Tari, 2016)

- Cessation for >1 year offers benefits similar to nonsmoker

- Among 150 patients with Graves hyperthyroidism and mild ophthalmopathy (proptosis <22 mm, no constant diplopia, mild lid and conjunctival inflammation) treated with radioactive iodine, progression (worsening of at least two of the following: 2 mm increase in proptosis or lid fissure; worsening vision; 2 point increase in CAS; onset diplopia) occurred in 6% of nonsmokers (stopped at least one year) and 23% of smokers (Bartalena, 1998).

- Stratified by degree of smoking:

Thyroid Regimen

- Choice of treatment for hyperthyroidism may impact TED

- In randomized trial of 313 patients with Graves hyperthyroidism, ophthalmopathy progressed in 63 of 163 (39%) patients treated with radioactive iodine (RAI) vs. 32 of 150 (21%) patients treated with antithyroid drugs (Traisk, 2009).

- Development of ophthalmopathy was higher among patients treated with RAI: 53 of 141 (38%) vs. 23 of 131 (18%).

- Concurrent short course of oral prednisone has been shown to be helpful at preventing worsening of TED following RAI

- In 150 patients with Graves hyperthyroidism and mild ophthalmopathy treated with RAI plus a 3 month course of oral prednisone, progression occurred in no nonsmokers or smokers (Bartalena, 1998).

Selenium

- Selenium is an oral antioxidant mineral supplement normally found in Brazil nuts, tuna, and dark green leafy vegetables.

- Marcocci (2011) performed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 159 patients with mild TED, giving 100 μg selenium selenite twice daily or placebo for 6 months, then followed for 6 months.

- At 6 months selenium was associated with reduced CAS scores, improved Quality of Life scores and slowed progression.

- No adverse effects were identified.

- This study was conducted in countries with relative selenium-deficient diets; further studies are planned.

- While hyperglycemia may occur, the dose employed for TED is lower than that typically associated with hyperglycemia.

Glucocorticoids

- Retrospective studies find efficacy for oral and intravenous corticosteroids in reducing inflammatory features, reversing some elements of disease, and possibly preventing progression in active TED (Stiebl-Kalish, 2009).

- Short-term oral corticosteroids at moderate doses (eg, prednisone 0.5-1.0 mg/kg/day) reduce inflammation but are not expected to alter the disease.

- The effect occurs within 24 hours and may minimally prevent progression, but significant reversal is uncommon without higher doses and sustained therapy.

- There are no absolute indications for corticosteroid therapy.

- A strong indication is significant inflammation.

- Progression of restrictive myopathy is considered by some to be a strong relative indication.

- Some prefer to treat progression of myopathy with radiotherapy.

- Some consider orbital decompression the best primary treatment for progressive myopathy, reducing congestion and ischemia.

- Compressive optic neuropathy is usually treated first with corticosteroids, but other modalities are commonly needed.

- Intravenous corticosteroid infusion can be arranged through an endocrinologist, rheumatologist or infusion center.

- Shams (2014) retrospectively studied 144 patients with active orbitopathy who were treated with intravenous corticosteroids for inflammation (80%) or more severe disease.

- These patients were referred to a tertiary care center in Vancouver, likely a skewed cohort with more advanced disease.

- Compressive optic neuropathy developed in 25 of the 144 patients (17%), at an average 8 months after presentation.

- Intravenous corticosteroids are not absolutely protective against compressive neuropathy and are not used alone to reverse sequelae; other modalities are added for more severe disease.

- None of 105 patients who received additional radiotherapy for progression of restrictive myopathy (88%) or steroid intolerance developed compressive optic neuropathy.

- Patients treated with radiotherapy also had significant reduction in restrictive myopathy.

- Severity of TED, smoking history, and diabetes were not significantly different between the groups.

- Kahaly (2005) compared once weekly intravenous methylprednisolone (0.5 g for 6 weeks and then 0.2 gm for six weeks) vs. higher-dose daily oral prednisolone (dosing comparable to prednisone: started at 0.1 g daily for a week, reduced by .01 g per week).

- Using a broad measure including improvement in proptosis, lid retraction, diplopia, quality of life, and visual acuity, efficacy was greater in the intravenous group (77% vs. 51%) at 3 months.

- Adverse events including weight gain, GI distress, sleeplessness, myalgias, hypertension, hirsuitism, and depression were higher in the oral steroid group.

- Due to a lack of placebo control, the efficacy of prednisolone is unknown.

- A double-blind trial comparing the methylprednisolone regimen with intravenous saline showed an 83% improvement rate vs. 11% in the placebo group (van Geest, 2008).

- Bartalena (2012) compared 3 dosage regimens of weekly intravenous solumedrol for moderate to severe active disease: a starting of dose of 250 mg (low dose), 540 mg (middle dose) or 830 mg (high dose) was maintained for 6 infusions, then halved for 6 infusions.

- The randomized, double-blind trial in 159 patients showed efficacy ranged from 28% in low-dose group, 35% in middle-dose, and 52% in high-dose at 12 weeks.

- Proptosis, lid retraction, and diplopia were not improved by any regimen.

- The high-dose regimen led to the most improvement in ocular motility and clinical activity score.

- “Efficacy” and patient expectation require careful definition when deciding whether to prescribe these intravenous glucocorticoid regimens.

- Several other regimens are described in the literature: 1 g daily intravenous methylprednisolone for 3 consecutive days for 5 weeks or 8 weeks; or 1 g daily for 5 consecutive days.

- Some of these protocols caused severe side effects including acute liver failure, stroke, and pulmonary embolism (Reviewed by Zang, 2011).

- Sisti (2015) studied 376 orbitopathy patients, 353 of whom were treated with intravenous methylprednisolone and 23 excluded.

- Regimen was 12 weekly infusions, starting with 4 infusions at 15 mg/kg (about 1 g) then 8 infusions at 7.5 mg/kg.

- Four patients developed acute liver disease, defined as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation above 300 U/l, with levels of 325–90 U/l.

- Liver disease was detected in 2 patients at week 6 and 8 during treatment and in 2 patients and 1-2 weeks after treatment (week 13 and 14).

- Three of the 4 patients required treatment, paradoxically, with additional corticosteroids to treat presumed autoimmune hepatitis.

- All 4 patients recovered.

- Patients with serologic evidence of active hepatitis or liver steatosis were excluded from treatment with intravenous glucocorticoids.

- Ebner (2004) studied intraorbital triamcinolone injections for patients with diplopia.

- 41 patients with orbitopathy for less than 6 months received placebo or 20 mg injected inferolaterally weekly for four weeks.

- Treated patients showed a reduction in field of diplopia and radiographic extraocular muscle size.

- While this treatment is part of the armamentarium for selected patients, steroid injections risk IOP elevation and vascular compromise.

Cyclosporine

- Kahaly (1986) performed a prospective, randomized trial with 40 patients using corticosteroids alone (10 weeks) or with 12 months of cyclosporine (5-7.5 mg/kg, administered twice daily).

- The cyclosporine prevented recurrence of inflammation in all but one patient, while about half (9 of 20) of the corticosteroid group had recurrence.

- As an alternative to the newer immunobiologic agents, cyclosporine, which is still commonly used in clinical practice for immunologic disease, is a therapeutic option.

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg)

- Baschieri (1997) demonstrated efficacy of IVIg for TED, but it is too costly for practical use.

- A 4-dose course of IVIg for a 70 kg person at 2/kg currently costs $25,000 (Medscape).

Adlimumab (Humira)

- Adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor against many immunologic diseases, not been found as useful for orbital inflammation.

- Humira costs ~$2,322 per 40/mg subcutaneous dose (drugs.com).

- Ayabe (2014) performed a retrospective chart review of 10 patients treated with adalimumab (at least 10 weeks, one 80-mg initial injection then biweekly 40-mg injection) for TED, 8 of whom were also treated with corticosteroids.

- The 5 patients with more significant baseline inflammation showed clinical improvement.

- Three patients had increased inflammation while on adalimumab.

- Adalimumab is effective at reducing inflammation but is not protective.

Rituximab (Rituxan)

- This anti-CD20 chimeric monoclonal antibody induces B-cell depletion and provides 10–12 month of protection against early B-cell and T-cell activation without significant immunosuppression.

- Stan (2015) performed a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 21 patients.

- Standard dose of two rituximab infusions, 1000 mg each, separated by two weeks

- Both groups improved over a year follow-up, with no significant difference in CAS or Quality of Life scores.

- There was no improvement over placebo at 24 or 52 weeks.

- No improvement in proptosis, lid retraction, diplopia or quality of life.

- The cost of 1000 mg rituximab is $9,000 (drugs.com).

- Silkiss (2010) reported on a case series of 12 patients and found improvement in CAS scores from baseline at multiple time intervals over a 52-week period.

- Salvi (2015) compared rituximab with intravenous methylprednisolone in a double-blind, randomized trial for moderate to severe disease in 32 patients.

- Rituximab was administered in two 1000-mg infusions or as a single 500-mg infusion.

- Intravenous methylprednisolone was administered as 830 mg weekly for 6 weeks and then 415 mg for 6 weeks (a cumulative dose of 7.47 g).

- CAS scores reduced by both protocols, extended beyond week 16 with rituximab.

- Disease reactivation was not observed in rituximab group; reactivation was observed in 5 patients after methylprednisolone within 6 months.

- Motility was better in the rituximab group at 52 weeks.

- Initially, the FDA approved rituximab for treatment of lymphoma at a dose of 1000 mg weekly for 4 weeks. The dose was halved in the FDA approval for rheumatoid arthritis.

- Salvi introduced further reduction for TED, to a single 500-mg infusion, with the sae 9–12 month B-cell depletion; this reduces cost and presumably risk.

- Side effects with rituximab include increased risk of viral infection, such as flu, and serum reactions during administration.

- A rare and potentially fatal infection, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is associated with multiple infusions and higher total doses than proposed for TED. The FDA has issued a black box warning regarding this consideration.

Tocilizumab (Actemra)

- Perez-Moreiras (2014) studied 18 patients prospectively with active TED, resistant to intravenous corticosteroids, and treated with tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the interleukin-6 receptor.

- The drug was administered intravenously monthly but at time of writing, it is self-administered subcutaneously.

- Side effects include gastrointestinal ulceration and respiratory infection.

- It is approved for giant cell arteritis at a dose of 162 mg once a week SQ.

- Actemera cost: 8 ml at 20 mg/ml is $850 (GoodRx).

- The drug showed improvement in proptosis, CAS score and strabismus reduction.

- A randomized, double-blind prospective trial was underway in 2018.

Teprotumumab (RG-1507)

- Teprotumumab is a monoclonal antibody against the insulin-like growth factor I receptor.

- Smith (2017) reported on a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled comparison of 88 patients with active, moderate to severe disease.

- Teprotumumab was administered intravenously once every 3 weeks for a total of 8 infusions.

- The only drug-related adverse event was hyperglycemia in diabetics.

- The study demonstrated statistically significant reductions in proptosis and CAS, and improvements in quality of life.

- Similarly, in 2020, Douglas et al reported improvements in diplopia, clinical activity score, diplopia, and quality of life in patients with active disease.

- Regarding patients with inactive disease, Ozzello et al documented improvements in proptosis and extraocular muscle volume in a patient with chronic disease and a low clinical activity score.

- Emerging case reports indicate a role for this agent in the management of dysthyroid optic neuropathy. While the evidence is anecdotal, the technology appears to be promising.

Orbital Radiotherapy

- Treatment of the orbit using radiotherapy (RT) for TED was first described in 1943 (Mandeville).

- Radiotherapy of the thyroid gland for Graves disease was first described in 1913 (Juler).

- There is a distinction between “activated” and “non-activated” lymphocytes.

- Non-activated lymphocytes are highly radiosensitive while activated lymphocytes are relatively radioresistant (Lowenthal, 1985).

- Lymphocyte apoptosis alone is not sufficient for orbital radiotherapy to break the inflammatory cycle of TED.

- Radiation doses as low as 1 Gy cause fibroblast terminal differentiation, which may remove the primary mediator of inflammation in the TED orbit.

- The typical dose is 20 Gy, delivered in 10 fractions over 10 to 12 days (Donaldson, 1973).

- Alternative protocols have been proposed including 2.4 Gy total, 16 Gy total, 10 Gy over 10 weekly doses, and 20 Gy over 20 weeks

- Prumell (2004) conducted a placebo-controlled study (sham RT as placebo), of RT for mild TED.

- “Mild” TED meant exclusion of “severe” periorbital swelling, Hertel measurements less than 25 mm, “moderate” motility disturbance, and presence of optic neuropathy.

- 23 of 44 (52%) treated patients had improved clinical findings at 12 months, compared with 12 of 44 (27%) in the sham group.

- 15 of 44 (34%) treated patients needed no further therapy compared with 7 of 44 (16%) in the sham group

- Of those patients requiring additional therapy, 7 vs. 2 in each group, respectively, required medical therapy, 3 vs. 1 underwent muscle surgery, and 10 vs. 9 underwent lid surgery.

- Considering the cost and morbidity of RT, this study did not prove a benefit of RT for mild disease.

- Gorman (2001) conducted a cross-over trial of RT vs. placebo in 53 patients with mild to moderate TED.

- One treatment was delivered to one orbit and the protocol was reversed 6 months later.

- Patients had at least 3 of 5 attributes: chemosis or lid edema; lid retraction perception of bulging; proptosis of 20 mm or more in at least one eye and less than 4 mm discrepancy in proptosis between both eyes; restrictive motility.

- Patients did not receive treatment with surgery or steroids for one year.

- One patient developed optic neuropathy and left the study after 3 months. One patient needed systemic corticosteroids.

- Whether treated early or 6 months later, no response to RT was detected.

- There was a slight decrease in muscle volume and proptosis with early treatment.

- Since the sham group did not progress or need additional treatment, this cohort included mostly inactive disease.

- The authors concluded that they were “unable to demonstrate any beneficial therapeutic effect” related to reversal of disease, not prevention of progression. Some therapies may reverse changes. Additionally, in patients with compressive optic neuropathy, reversal of the vision loss is an important goal.

- One potential advantage of RT for TED is the option to discontinue systemic glucocorticoids in patients with steroid-dependent disease.

- In a series of 311 patients with severe TED treated with RT, 76% were able to discontinue corticosteroid therapy (Donaldson, 1973).

- In another series, 54 of 59 patients (92%) were able to discontinue glucocorticoid therapy after orbital RT (Li, 2011).

- Side effects of RT include dry eye, hair loss, periorbital edema, and conjunctival injection.

- Orbital inflammation may temporarily be worsened during RT administration, and oral prednisone may ameliorate the symptoms.

- Radiation retinopathy after orbital RT for TED has been described but mostly at higher than the currently recommended dosages (Kinyoun, 1984).

- Subtle vascular changes including microaneurysms, cystoid macular edema, punctate hemorrhages, and areas of capillary nonperfusion may be evident on only fluorescein angiography (Marcocci, 2003).

- The lens appears to tolerate a dose of 500 cGy in a single fraction and 100–5,000 cGy in multiple fractional doses (Beckendorf, 1999).

- Several studies have found no increased risk of cataract formation after orbital RT for TED (Walkelkamp, 2004; Petersen, 1990).

- Concurrent risk factors for accelerated cataract formation include diabetes and use of glucocorticoids.

- There are no reported cases of secondary malignancy after orbital RT for TED.

- There are no consensus guidelines on indications of RT for TED.

- A report from the American Academy of Ophthalmology found that extraocular motility may be improved and that efficacy for compressive optic neuropathy has not been proven (Bradley, 2008).

- For patients with compressive neuropathy, the addition of RT to corticosteroids reduces the need for decompression surgery compared with steroids alone (Jeon, 2012).

- Radiotherapy may be useful in preventing progressive expansion of muscles and recurrence of vision loss following successful orbital decompression.

- The Academy report found a limited role for non-sight-threatening disease.

Montelukast (Singulair)

- Montelukast is a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor antagonist that inhibits the inflammatory effect of mast cells.

- Mast cell degranulation releases preformed mediators such as histamine and serotonin and leads to the expression of multiple inflammatory mediators.

- Lauer (2008) found that 6 of 12 patients with mild to moderate TED reported improvement in tearing, dryness, and itching within 3 weeks of starting montelukast 10 mg daily with cetirizine 10 mg daily.

- A placebo-controlled trial is needed to assess the efficacy of montelukast in early disease to prevent progression.

Conclusion

- Until recently, patients with mild to moderate TED received little nonsurgical management, with clinicians choosing observation and short courses of oral corticosteroids as needed.

- Patients were reassured, perhaps incorrectly, that surgical options were available to reverse the sequelae of their eyelid, muscle, and orbital disease once their orbital and thyroid disease stabilized.

- Patients with severe disease were treated with high doses of corticosteroids, orbital radiotherapy, and urgent surgical decompression.

- As of this writing, the goals are early intervention, coordinated medical care, risk factor modification, medical control and reversal of orbitopathy, and minimizing overall disease prior to surgery.

- The variety of nonsurgical management options available to the current physician has created a challenge in deciding how to apply and optimize their use.

References

- Bahn RS. Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726-738.

- Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Tanda ML, et al. Cigarette smoking and treatment outcomes in Graves ophthalmopathy. Ann Int Med. 1998;129:632-635.

- Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Bogazzi F et al, Use of Corticosteroids to Prevent Progression of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy after Radioiodine Therapy for Hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1989; 321:1349-1352.

- Bartalena L, Krassas GE, Wiersinga W, et al. Efficacy and safety of three different cumulative doses of intravenous methylprednisolone for moderate to severe and active Graves’ orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4454-63.

- Baschieri L, Antonelli A, Nardi S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin versus corticosteroid in treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy.Thyroid. 1997;7:579-585.

- Beckendorf V, Maalouf T, George JL, et al. Place of radiotherapy in the treatment of Graves’ orbitopathy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:805.

- Bradley EA, Gower EW, Bradley DJ, et al. Ophthalmic technology assessment: Orbital radiation for Graves ophthalmopathy. A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2008; 115:398.

- Bumann J, Santo-Hoeltje L, Lofer H, et al. Radiation-induced alteration of the proliferative dynamics of human skin fibroblasts after repeated irradiation in the subtherapeutic dose range. Strahlenther Onkol. 1995; 171:35.

- Chundury RV, Weber AC, Perry JD. Orbital radiation therapy in thyroid eye disease. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016; 32:83.

- Dawicki W, Marshall JS. New and emerging roles for mast cells in host defence. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:31-8.

- Donaldson SS, Bagshaw MA, Kriss JP. Supervoltage orbital radiotherapy for Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;37:276.

- Douglas RS, et al. Teprotumumab for the treatment of active thyroid eye disease. N Eng J Med, 382:341-352, 2020

- Ebner R, Devoto MH, Weil D, et al. Treatment of thyroid associated ophthalmopathy with periocular injections of triamcinolone.Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1380-1386.

- Gorman CA, Garrity JA, Fatourechi V, et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of orbital radiotherapy for Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1523.

- Jeon C, Shin JH, Woo KI, Kim YD. Clinical profile and visual outcomes after treatment in patients with dysthyroid optic neuropathy. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2012; 26:73-79.

- Juler FA. Diseases of the orbit acute purulent keratitis in exophthalmos goiter treated by repeated tarsorrhaphy, resection of cervical sympathetic and x-rays: retention of vision in one eye. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1913;33:55.

- Kahaly G, Schrezenmeir J, Krause U, et al. Cyclosporin and prednisone versus prednisone in treatment of Graves’ ophthalmopathy: a controlled, randomized and prospective study.Eur J Clin Invest. 1986;16:415-422.

- Kinyoun JL, Kalina RE, Brower SA, et al. Radiation retinopathy after orbital irradiation for Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1473.

- Li Yim JFT, Sandinha T, Kerr JM, et al. Low dose orbital radiotherapy for thyroid eye disease. Orbit. 2011; 30:269.

- Lowenthal JW, Harris AW. Activation of mouse lymphocytes inhibits induction of rapid cell death by x-irradiation. J Immunol. 1985;135:1119.

- Mandeville F. Rontgen therapy of orbital-pituitary portals for progressive exophthalmos following subtotal thyroidectomy. Radiology. 41:268,1943.

- Marcocci C, Kahaly GJ, Krassas GE, et al. Selenium and the course of mild Graves’ orbitopathy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1920-31.

- Marcocci C, Bartalena L, Rocchi R, et al. Long-term safety of orbital radiotherapy for Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003; 88:3561.

- Ozzello DJ, et al. Early experience with teprotumumab for chronic thyroid eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol Case Reports, 2020, epub ahead of print

- Perez-Moreiras JV, Alvarez-Lopez A, Gomez EC. Treatment of Active Corticosteroid-resistant Graves’ Orbitopathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg.2014;30(2):162-7.

- Petersen IA, Kriss JP, McDougall IR, Donaldson SS. Prognostic factors in the radiotherapy of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;19:259.

- Prummel MF, Terwee CB, Gerding MN, et al. A randomized controlled trial of orbital radiotherapy versus sham irradiation in patients with mild Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:15.

- Sadeghi-Tari A, Jamshidian-Tehrani M, Nabavi A, et al: Effect of smoking on retrobulbar blood flow in thyroid eye disease. Eye. 2016; 30:1573-1578.

- Salvi M, Vannucchi G, Curro N, et al. Efficacy of B-cell targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with active moderate to severe Graves’ orbitopathy: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:422-31.

- Shams PN, Ma R, Pickles T, et al. Reduced risk of compressive optic neuropathy using orbital radiotherapy in patients with active thyroid eye disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:1299-305.

- Silkiss RZ, Reier A, Coleman M, Lauer SA: Rituximab for thyroid eye disease. Ophthal Pl Reconstr Surg. 2010; 26:310-314.

- Sisti E, Coco B, Menconi F, et al. Intravenous glucocorticoid therapy for Graves’ ophthalmopathy and acute liver damage: an epidemiological study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172:269-76.

- Smith TJ, Kahaly GJ, Ezra DG, et al: Teprotumumab for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:1748-1761.

- Stan MN, Garrity JA, Carranza Leon BG, et al. Randomized controlled trial of rituximab in patients with Graves’ orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:432–41.

- Stiebel-Kalish H, Robenshtok E, Hasanreisoglu M et al. Treatment modalities for Graves’ ophthalmopathy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2708-16.

- Traisk F, Tallstedt L, Abraham-Nordling M, et al. Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy after treatment for Graves’ hyperthyroidism with antithyroid drugs or iodine-131. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3700-7.

- Van Geest RJ, SasimI V, Koppeschaar HP, et al. Methylprednisolone pulse therapy for patients with moderately severe Graves’ orbitopathy: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008; 158: 229-237.

- Wakelkamp IM, Tan H, Saeed P, et al: Orbital irradiation for Graves’ ophthalmopathy: is it safe? A long-term follow-up study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1557.

- Zang S, Ponto KA, Kahaly GJ. Intravenous glucocorticoids for Graves’ orbitopathy: efficacy and morbidity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:320-32.