Otoplasty and Earlobe Surgery

Updated May 2024

Dissatisfaction with the appearance of the external ear is common among people with congenital and acquired minor or major ear deformities. In the absence of pathology of the middle and inner ear, many external ear deformities can be successfully repaired as office or outpatient procedures. Lop ear and bat ear, the most common types of congenital excessive protrusion of the external ear, and acquired earlobe deformities are the problems most frequently presenting to the oculofacial plastic surgeon’s practice. Reconstruction for microtia and more complex deformities is beyond the scope of this article.

Goals of the procedure

Primary goals

- Improved appearance of the prominent ear

- “Normal” ears are neither beautiful nor ugly; they are simply not noticed by observers.

- “Normal” ears are usually not perfectly symmetric.

- Correction of external ear deformities is aimed at making the ear more unremarkable rather than more beautiful.

- Reduction of the cephalo-auricular angle

- The cephalo-auricular angle is defined as the angle between the helix and the scalp posterior to the ear and is normally 20–30 degrees with a corresponding distance of 15–20 mm between the lateral helix margin and the head.

- Reduction of the concha-scaphal angle

- The conchal-scaphal angle is defined as the angle between the conchal bowl and the scapha (flat area between the helical rim and the antihelical fold). It is considered excessive when greater than 90 degrees.

- Reduction of conchal excess and reduction of the angle between the concha and the mastoid

- The normal conchal protrusion from the mastoid is 12–15 mm.

- Creation of normal helix profile on frontal view

- The normal lateral helix protrudes more laterally than the antihelix for 2–5 mm from the superior pole to at least mid-ear or beyond.

- Creation or maintenance of other normal relationships

- Superior ear attachments are in the same axial plane as the inferior eyebrow.

- Inferior ear attachments are in the same axial plane as the columnar base.

- Tragus is halfway between the inferior and superior attachments.

- Long axis of ear is inclined 20 degrees posterior to coronal plane.

Indications and contraindications

Indications

- Upper ear deformity or variation

- Lop ear

- Bat ear

- Trauma

- Ear lobule deformity

- Earring avulsion

- Gauged ear lobule

- Pixie deformity after face lift

Contraindications

- Relative

- Acute or chronic untreated otitis media, chrondritis, scalp or facial infection

- Existing ear piercing can influence the approach and goals of surgery. Earrings can be a source for bacterial infection.

- Strong resistance from a child

Preprocedure evaluation

Patient history

- Congenital

- Acquired

- Acute or chronic trauma – crib positioning of the head on the still malleable auricles can affect ear prominence. Matsuo et al. reported prevalence of 0.4% prominent ear at birth, but 5.5% by one year of age (Matsuo, Clin Plast Surg, 1990)

- Patient or parents might report self-consciousness or psychological problems

Clinical examination and preoperative assessment

- Each ear evaluated separately

- Critical sites

- Antihelix hypoplasia or underdevelopment

- Helical prominence and/or deformity

- Conchal bowl size and configuration

- Cartilage strength and malleability

- Lobule protrusion

- Cephalic position asymmetry

- Cephalo-auricular angle

- Measured at the superior pole, the external auditory meatus, and the antitragus

Alternatives to the procedure

Incisionless surgery using complex suture placement

(Fritsch 1995): See Fritsch in references.

Molding

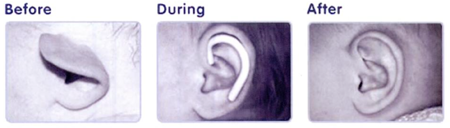

During early infancy, the ear cartilage is more malleable and viscous and less elastic than it will later be (possibly related to maternal estrogen levels), so there is an opportunity to mold the ear (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nonsurgical molding in early infancy (from Adamson 2011).

- Best results are seen for molding treatment begun within the first 3 days of life and continued until 6 months of age.

In adulthood, laser reshaping of the auricular cartilage followed by application of external conformers has been studied (Leclere, Lasers Surg Med, 2011).

- Patients wear conforming silicone elastomer molds for 4–6 weeks after in-office laser treatment.

- The entire system is currently marketed by Numenis as Cartilaze in the US.

Techniques

- Otoplasty to create or augment an antihelix for prominent ears:

- Most procedures are performed under local anesthesia alone or with IV sedation. General anesthesia can be used if required for a small child or desired.

- Consider prophylactic systemic antibiotics.

- Marking: The helical rim is folded back against the head and the proper location for the antihelix will almost always be obvious. Markings are made on the lateral/anterior surface and on the medial/posterior surface.

- Local field block with 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine and 0.75% Marcaine with hyaluronidase

- 1% lidocaine (with or without epinephrine) infiltrated SQ to the medial and lateral auricular surfaces; some have suggested that epinephrine is contraindicated for possible risk of ischemia.

- Skin incision is made on lateral/posterior surface with subsequent dissection anteriorly and posteriorly to widely expose the cartilage surface. An ellipse of skin can be removed if desired, similar in shape to that commonly harvested for skin grafting.

- Blunt subcutaneous dissection between the skin and anterior cartilage with mosquito clamp, freer elevator, or tenotomy scissors is accomplished via the antitragus-helical fissure.

- Abrasion of the perichondrium and antihelical cartilage is accomplished with a small rasp or a Stenstroem otoabrader to weaken the elastic fibers and obtain a bending-away effect.

- Parallel full-thickness incisions in the cartilage anterior and posterior to the desired location of the antihelical fold have been described (see references), but have been abandoned by many surgeons.

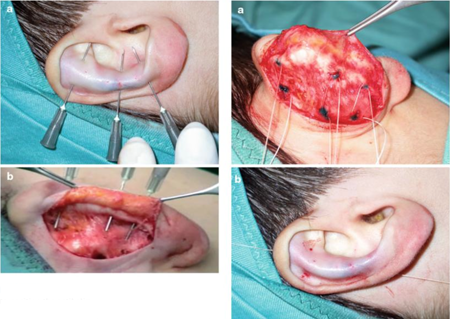

- The helical rim is again folded back against the head and straight needles dipped in methylene blue are passed to mark 3 sets of points (Figure 2):

- Inferiorly through the tail of the antihelix on the scaphal and the conchal side

- Midway at the antihelix bifurcation on the scaphal and conchal side

- Superiorly between the triangular fossa and the scapha to mark the superior crus of the antihelix

- Three partial-thickness 3-0 vicryl Mustarde mattress sutures are placed at the 3 sets of points on the posterior cartilage surface, starting inferiorly, to create the bending of the antihelix (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Marking and Suture Placement (from Shiffman 2013).

- Reduction of conchal prominence can be performed if desired (see below).

- Additional sutures to further close the cephalo-auricular angle can be placed from the mastoid fascia to the posterior conchal cartilage (aka Mastoid Hitch).

- Closure of the skin wound is accomplished with the surgeon’s preference of suture.

- Prolene sutures on the anterior ear surface tied over bolsters can be placed to augment the antihelix and reduce tension on the vicryl mattress sutures (Figure 3).

Figure 3. External splinting sutures (from Shiffman 2013).

- Dressing: Light packing with cotton balls moistened with mineral oil followed by coronal Kerlix gauze is applied for 24 hours

- Patient is advised to wear for 6 weeks a snug tennis headband while sleeping to avoid inadvertent forward bending of the ear.

- Conchal reduction for deep and hypertrophic concha

- Can be performed alone, but is most commonly performed as part of the antihelix otoplasty described above

- A crescentic ellipse of full-thickness conchal cartilage is excised from the junction of the posterior wall and the floor of the concha. Wide skin undermining of the conchal cartilage anterior surface permit closure of this defect without creation of visible skin folds.

- The cartilage defect is closed with multiple partial thickness 4-0 clear nylon or vicryl sutures.

- Localized helical prominences (such as elf ear or Spock ear) can be removed by excision of a fusiform skin segment from the outer helical rim, and trimming of the excess cartilage to create the desired shape. Skin is closed with permanent suture, removed 7 days postoperatively.

- Avulsed earring repair and ear piercing closure

- Healing after avulsion typically creates a bifurcated lobule. The skin to be excised from within the bifurcation is marked, and local infiltration of anesthetic is accomplished. For unwanted ear piercings, skin will be excised from within the tunnel to create a small ellipse.

- Skin is excised and closure is accomplished in layers for the deep soft tissue and for the anterior and posterior skin edges.

- Repair for gauged ear lobules

- Very large piercing holes can be created by gauge earrings in both men and women. When they are no longer desired, reconstruction can be accomplished under local anesthesia using simple flaps and closure in multiple layers.

Patient management: treatment and follow-up

Postoperative instructions

- Systemic antibiotics and analgesics are prescribed

- Patient is advised for 6 weeks to wear a snug tennis headband while sleeping to avoid inadvertent forward bending of the ear.

- Followup for evaluation and suture removal at 1 week

Other management considerations

- Most patients will have an uncomplicated postop course and will be pleased with the improvement of ear appearance.

- Occasionally there is need for additional surgery due to persistent asymmetry or under/overcorrection.

Preventing and managing treatment complications

- Hematoma presents with pain and is usually the result of insufficient hemostasis. Hematomas must be urgently drained to prevent tissue necrosis, with additional surgical coagulation as required.

- Infection: Systemic antibiotics are recommended. Surgical asepsis is obviously important as well.

- Skin necrosis: Avoid excessive pressure dressings, and drain hematomas.

- Wound dehiscence: Careful wound approximation is necessary.

- Asymmetry and under- and over-correction: Careful intraoperative assessment of symmetry of correction is helpful. Occasionally, refinement or enhancement secondary surgery might be necessary to satisfy patient concerns.

- Postauricular skin retraction and/or scarring can probably best be avoided by not removing any skin from the postauricular sulcus.

Disease-related complications

- None

Historical perspective

- In 1941, Hamilton Baxter first described cartilage removal and suturing to create an antihelical fold.

- In 1963, John Mustarde first described a method for creating an antihelical fold using permanent conchoscaphal mattress sutures.

- In 1968, Furnas described a technique for conchal setback using permanent conchomastoid sutures.

References and additional resources

- Adamson PA, Littman JA. Aesthetic Otoplasty. Peoples Medical Publishing House 2011.

- Baxter H. Plastic correction of protruding ears in children. Canadian Medical Journal 45:217-220, 1941.

- Becker DG et al. Analysis in Otoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clinics of North America 14:63-71, 2006.

- Brenda E et al. Otoplasty and its origin for the correction of prominent ears. J Craniomax Surg 23:99-104, 1995.

- Byrd HS et al. Ear molding in newborn infants with auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 126:1191-200.

- Elsahy NI. Technique for correction of lop ear. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990.

- Fritsch MH. Incisionless otoplasty. Laryngoscope 105:1-11, 1995. (A copy of his recent chapter can be downloaded from his website: http://www.eardoc.us/otoplasty.php?box=3)

- Heppt WJ. The incision-excision technique in minor auricular deformities. Facial Plast Surg 22:287-292, 2004.

- Hinderer UT et al. Otoplasty for Lop Ear. Aesth Plast Surg 11:75-80, 1987.

- Horlock N et al. Five year series of constricted ear corrections: development of the mastoid hitch as an adjunctive procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg 102:2325-2332,1998.

- Leclere FMP et al. Cartilage reshaping for protruding ears: a prospective long term follow-up of 32 procedures. Lasers Surg Med 43:875-880, 2011.

- Leonardi A et al. Neonatal molding in deformational auricular anomalies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 16: 1554-58, 2012.

- Maniglia AJ, Maniglia JV. Congenital lop ear deformity. Otolaryngol Clinics North Am 14:83-93, 1981.

- Matsuo K et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities. Clin Plast Surg 17:383-95, 1990.

- Shiffman MA. Advanced Cosmetic Otoplasty. Springer 2013.

- Zwiren J. Gauge earlobe repair. 2011. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GKxD3JE0NUA